The first protest tent on Rothschild Boulevard in Tel Aviv was set up by Daphni Leef after her lease expired, and after the high rental prices did not allow her to find a new apartment. The massive protest that followed that lone tent erupted due to soaring housing prices, yet failed miserably in achieving its aims – actually lowering them.

In 2011, purchasing an average apartment in Israel cost "only" 127 average monthly salaries per individual. Now, at the start of the new decade, 148 monthly salaries are required. Around the world, however, a series of government and civic initiatives are proving that a decent home can be guaranteed at reasonable prices for all citizens.

Collective rent bargaining in Sweden

The Israeli Key Fee plan, whose roots go back to the British Mandate, is intended to enable long-term and protected leases at discounted prices. The program was popular especially in the big cities and was intended for new immigrants who were encouraged to purchase discounted apartments. Today there is not much left of the plan, which encompasses between 20,000 and 30,000 properties, half of which are for housing, and most of which are occupied by elderly people who bought the apartments four or five decades ago.

The rent in Sweden works in a similar manner, and includes paths of protected tenancy and of a "right of residence" that includes a partnership with the association that manages the property. This method of renting is the product of collective bargaining between tenants’ unions and homeowners' unions.

Apartments that are officially and legally rented out in Sweden are owned by cooperatives, government-owned companies or local authorities. For tenants, an organization will present a statutory holder who negotiates on their behalf with the entities that rent the apartments, similar to negotiations between workers' organizations and employers about wages.

This structure allows for control over housing prices and maintains market competition, so that even in periods of rising prices, an arbitrary increase in rent can be avoided. According to critics, this is a cumbersome mechanism that produces long waiting times for apartments in areas of demand, but there is no doubt that it also allows the lower-income people to live in quality apartments and enjoy high residential security at an affordable price.

Affordable public housing in Vienna

According to the State Comptroller's report, at the end of 2019, there were approximately 53,000 public housing units in Israel. Eligible people had to join waiting lists for an apartment, meanwhile the number of apartments that were planned to be added to the pool was a few hundred. Less than 5% of those entitled to public housing, according to the definitions of the law, are expected to be granted the coveted public housing unit.

The public housing system owned by the Vienna municipality is more than 100 years old. 60% of Vienna's residents – or about 450,000 households – live in public housing. Half of the apartments in Viennese public housing are owned by the municipal government while the others are owned through cooperatives. Contrary to the Israeli image of public housing as a welfare institution intended for the poor, Viennese public housing is also intended for the middle class, and is suited for renters who earn about 40,000 Euros a year. The tenants are also not required to vacate the apartment if their rent increases.

Rent in public housing apartments is linked to income, and is meant to take up about 20-25% of household income. In Israel, by comparison, the average expenditure on rent as of 2020 was 37% of an individual’s wages.

Public housing in Vienna is funded by a one percent municipal tax on the salaries of all residents, the payment of which is divided between the workers and the employers.

"Our policy is based on a basic statement," said Kurt Puchinger, who is the director of the Viennese housing and planning department, in an interview with the London publication New Statesman. "The right to housing is one of human rights – this has been Vienna's philosophy for over a century."

Government subsidies on mortgage interest in Finland

In 2017, the Israel Mortgage Advisors Association published a position paper criticizing mortgage interest rates for eligible people who have difficulty purchasing a mortgage. According to the advisers, the interest rate on these mortgages is many times higher than what buyers might get in the free market; the short validity of eligibility puts pressure on candidates, and the maze of endless bureaucracy makes it difficult for even the most determined to exercise their eligibility. The depleted fund of subsidized mortgages means that only a few thousand people get to take advantage of this system in any case.

According to the OECD, government expenditure on support for home buyers in Israel is about 0.1% of GDP, and most consists of grants for the purchase of an apartment (price per occupant). In contrast, Finland tops the list of countries that support buyers, with a set of national mortgage grants that makes up 0.9% of GDP, almost 10 times more than in Israel.

The national mortgage guaranteed by the state in Finland is given only to buyers with equity of 50% of the property, but only on the condition that they intend to live there. The goal is to fight developers’ takeover of the market. Mortgages intended for young couples purchasing a first apartment allow for a ten-year mortgage at a subsidized interest rate, with the state financing 70% of the interest payments when it crosses the 3.8% threshold. The average grant amounts to 140,000 euros, and in the capital city of Helsinki, grants reach up to 215,000 euros, depending on the size of the property. The government grant allows for the financing of affordable mortgages at 15% -20% of the market price.

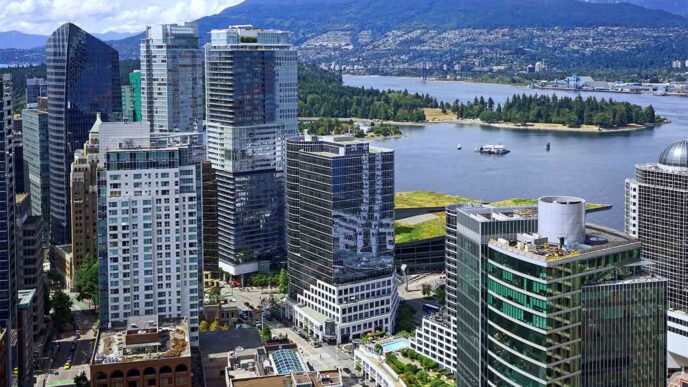

No ghost apartments in Canada

Economic logic ostensibly dictates that high housing prices in Israel are a derivative of a "supply crisis." That is to say, there are not enough vacant apartments to satisfy the demand of buyers and tenants. However, according to a report by the Central Bureau of Statistics, as of 2018 there were 170,000 vacant housing units in Israel (approximately 6.5% of all housing units in the country). About 44% of the empty apartments (73,000) have been defined as "ghost apartments" that stand empty for at least nine months each year, with most of them being used as vacation apartments by wealthy citizens and foreign residents. Many of these apartments are located in the heart of high-demand areas —Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, and more recentlyNetanya, and are raising housing prices.

One of the effective tools for dealing with ghost apartment owners is the imposition of a double property tax, which in practice constitutes a fine for maintaining an empty apartment. This increased collection should be carried out by the local authorities, with the backing of the state. However, according to a report by the State Comptroller published several weeks ago, most of the authorities in Israel did not act on the issue at all.

In Vancouver, Canada, this policy has been a great success. In the last decade, many luxury towers have been built in the city, and those with means from around the world have kept an eye on the city. The rate of apartment sales in the towers jumped by 300% and apartment prices throughout the city began to rise rapidly.

An inspection by the municipality revealed that a significant proportion of the apartments stand empty, and most of them are used as vacation apartments for wealthy Americans, Chinese and Japanese. In order to reduce the phenomenon, the municipality decided to impose a tax on the maintenance of an empty apartment, at a rate that has accumulated since 2018 to about 3% of the value of these apartments. Although the price tag is quite negligible, several hundred thousand Canadian dollars for apartments with an average cost of 5 million dollars, the municipality claims that the tax was enough to make many give up the pleasure.

A study conducted in recent years by the Department of Public Policy at Simon Frazier University has shown another effect of the tax: the gradual decline in housing prices led to speculators – who had purchased investment apartments in the belief that prices would continue to rise – selling their properties, which was another contribution to cooling off the housing market in the city.

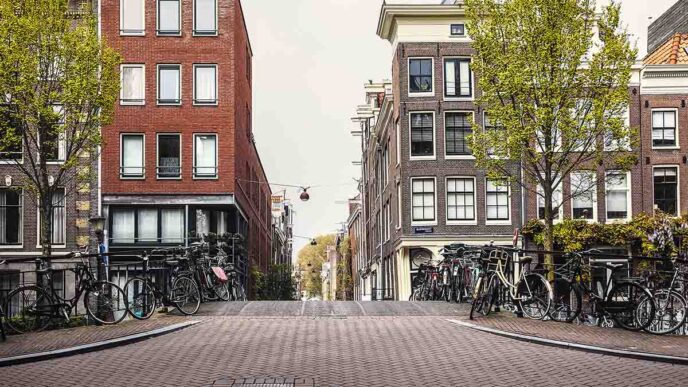

Dutch tenants' associations: Non-profit renters

Another initiative to reduce rents can be implemented with almost no government or municipal involvement. According to a position paper on the housing issue published by the Adva Center, "Tenants' Associations" own about 30% of the apartments for rent in the Netherlands, and about 40% of the apartments for rent in the major cities in the country. The associations are third sector non-profit organizations that build, maintain and rent apartments.

Currently, Dutch associations do not receive funding from the state (they are entitled to regulatory relief and reduced tax payments) and the funding comes from the rent paid by the tenants and the sale of apartments.

The rent charged by the associations is about 25% lower than the rent in the private market, and over 40% of the tenants are entitled to government assistance in rent in addition.

Until 2000, the program received government funding and appealed to the entire public, regardless of socioeconomic status. Since then, sweeping support for European Commission pressure (which saw it as a hit on the free market) has been abolished and most tenants come from low-income earners or designated populations: the elderly, immigrants, the homeless and so on.