The view along the northern highway is nothing if not pastoral. Rural villages are scattered between green wooded hills. Only the multitude of military vehicles and antennas from IDF bases give a hint of the storm that could break out. A look to the north serves as a reminder that the nearby villages lie across the border, in Lebanon.

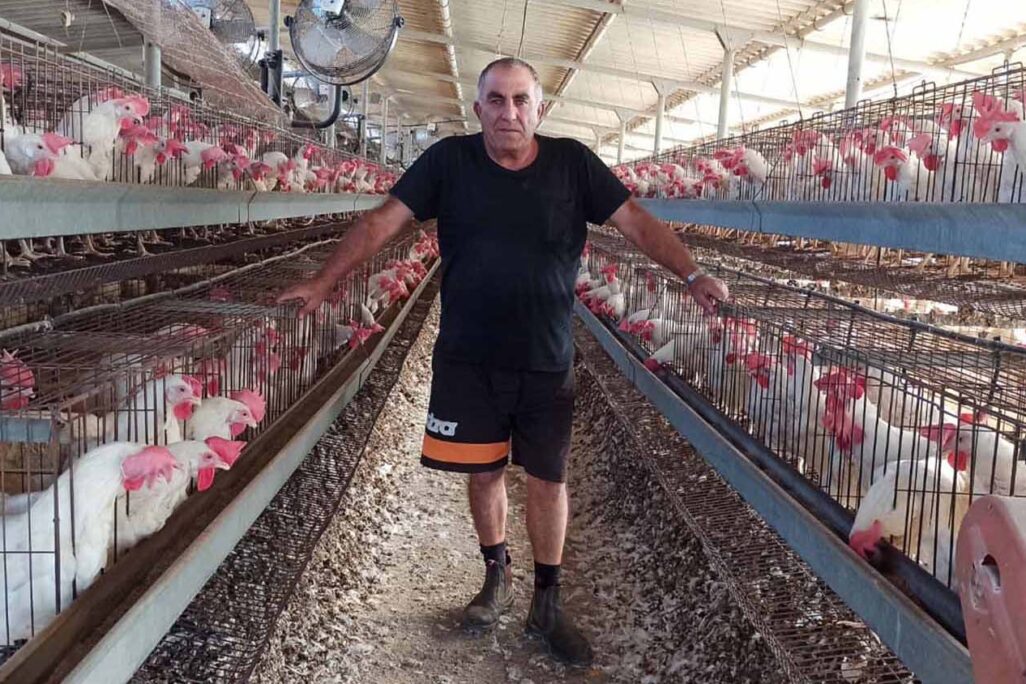

At the entrance to Moshav Dovev, as with most of the other moshavim along the way, one immediately notices the vast expanses of chicken coops. The egg industry, which provides a livelihood for many families throughout Northern Israel’s Galilee region, tells the stories of Israelis who have lived for years on the front lines of international conflict, but feel abandoned when it comes to the home front.

At the top of the poultry farmers’ agenda is the fight against the Finance Ministry’s reforms to the egg industry, which would do away with production quotas, reduce state oversight of prices, and open the market to imports, threatening the ability of the poultry farmers to sustain themselves.

“My feeling,” says poultry farmer David Yekuti (68), “is that no one is looking out for us, even though we’re the ones living on the border and sustaining the economy.”

Background: Eggs Head North

Moshav Dovev was founded in 1957 by 50 families of olim from Iran and Morocco. Over the years, it grew to 130 families, and today its population stands at around 500 people. The majority of the residents work in agriculture, mainly in the chicken coops. For decades, they raised broilers (chickens intended for meat) until they turned all of their coops over to egg production in 1982 .

“There was a state policy to cease egg production in the center of the country,” explains Yekuti, a member of the founding generation of the moshav. “So they transferred the production quotas to us and we converted the coops from meat production to egg production.”

Yekuti explains that the reason behind transferring the coops was the weather.

“It’s cold in the Galilee so it’s worthwhile to raise sturdier laying hens. Broilers are sensitive, they get a lot of diseases and you need a really big coop. Only kibbutzim or rich people can grow broilers,” he says.

Quotas: Up for Sale

Yekuti’s parents came to the moshav as it was being founded as part of a program called “From the City to the Village.”

“[Prime Minister David] Ben-Gurion called for olim, both those who were newly arrived and those who had been in Israel for some time, to move to the country’s geographical and social periphery,” he says. “In order to encourage people to come to the moshavim and to live along the border they offered incentives for them to work in agriculture.”

For years, he worked on his parents’ farm, and today it belongs to him.

“I inherited the quota allotment from my parents,” says Yekuti. “Everyone has their own coop and their own production cap. The limit is between 2,500 and 2,600 chickens. If someone has more, it means they bought someone else’s allotment.”

Cycles and Numbers

Yekuti explains the costs of raising egg-laying chickens, which are substantive.

The laying hens grow over a two-year cycle. A growing cycle begins with the purchase of about 2,500 hens or more (depending on the limit), which alone costs around “70,000 shekels [about $22,500], and that’s before a single egg has been laid,” says Yekuti.

“There are capital expenditures,” Yekuti continues. “Before you bring in the flock you have to prepare the coop: washing and cleaning, removing trash, disinfecting. When you bring the hens in, you have to vaccinate them, there’s veterinary supervision. In the first two months after bringing in the flock, we feed the hens a nutrient mix, and they still don’t lay eggs. At this stage, it’s only an expenditure until the hens start laying.”

The nutrient mix is the main expense for the coop, making up about half of total expenditures. A hen eats around 120 grams a day on average, which can be calculated two years in advance to understand the investment.

“Lately, corn prices have gone up, which means the price of the nutrient mix has gone up. We’re paying more, but the cost of eggs has stayed the same,” Yekuti explains.

And of course there are operating expenses. Daily care for the chickens includes feeding, gathering eggs, and performing health checks.

“In the first year, there are no profits because the eggs are still very small, so you have to absorb the costs,” he says. “In the second year, we actually recoup the expenses of the first year. But in the second year there’s natural mortality among the hens, sometimes there’s a power or water outage, sometimes you don’t notice that a hen stopped laying eggs, and in the meantime those hens are eating and not producing eggs.”

Yekuti says that he has 4,000 chickens in his coop. In the current flock, which he has been raising for a year and a half, that comes out to 3,200 after natural mortality rates. After six months

“At the peak of production, we produce 125 packages of eggs a day (about 3,750 eggs on average), and now we’re already down to 90 packages a day (an average of 2,700 eggs). It’s a substantial drop-off.”

“You can make a living from raising laying hens, but not a steady salary,” Yekuti explains. “You can’t make millions. It comes out to an average of 5,000 to 7,000 shekels a month (about $1,600 – $2,250). That’s in a good situation, when the chickens stay healthy and continue laying eggs. It’s also a matter of luck.”

Egg Prices: No Control

Yekuti explains that they have no control over the prices of eggs, that these are determined by the supermarket chains, often to the fiscal loss of the farmers.

“For each package of 30 eggs, we get 14 shekels ($4.50) from the distributor before taxes,” he says. “People go to the supermarket and see that a pack of eggs costs 30 shekels [$9.65] and ask: Why so much? So they should know: from the moment that we sell the eggs to the distributor for 45 agurot (14 cents) an egg, we have no control over the price.”

The distributors determine the price of eggs based on their sizes. They sort eggs and discard dirty or cracked eggs, then sell them to the supermarket chains.

“Every distributor has an agreement with certain supermarket chains. Sometimes there are also middlemen,” Yekuti says. “If the price of eggs at the supermarket goes down, it comes out of the price they pay us, because the distributors and the supermarket chains aren’t giving up on their share. They print the coupon and we pay the price.”

According to Yekuti, after accounting for chicken feed, water, electricity, spraying for pesticides, medicine, and veterinary care, he is left with seven or eight shekels ($2.25-$2.57) per pack of eggs. That comes out to about 25 agurot (8 cents) per egg.

The Reform: “It Will Destroy Farmers”

The reform being pushed by the Finance Ministry would do away with the quotas allotted by the Poultry Farmers’ Council, limit government oversight of the price of eggs (which is done by the Price Committee of the Finance and Agriculture Ministries), and open the market to imports.

However, in response to pressure from certain Members of Knesset and the agricultural lobby, the reform will not be included in the upcoming Arrangements Law and will instead be discussed in the coming months as separate legislation, but it’s clear to the farmers that the fight for their modest source of income is far from over.

David Yekuti: “The government wants to impose reforms without offering grants or loans at preferred rates. This will really destroy the poultry farmers”

Poultry farmers have been through government reforms to their industry before. In 2017 there was the “Green Coop” reform, which aimed to move existing chicken coops from the centers of kibbutzim and moshavim to more remote areas for sanitary and environmental reasons, as well as to improve efficiency and animal welfare. The reform also imposed more stringent veterinary and environmental oversight.

“We adhere to all of the regulations, down to the letter of the law,” says Yekuti. “But now, there is a demand to build free-range coops. These are totally different from what we have. Our coops have cages. The new coops take up a lot more space, and they’re built so that the hens can roam freely and have a cubby to lay their eggs in.”

Yekuti says that free-range coops are much better for chickens, farmers and consumers. However, the process of building requires the farmers to tear down the existing coops and totally rebuild, and is very expensive, costing about 1 million shekels ($320,000)

“In the meantime, until the coop is ready, you can’t raise chickens and you need to make a living somehow,” he says. “But nobody’s going to give a poultry farmer a loan for a million shekels to build a new coop, certainly not to older farmers. How would they pay it back? And the government wants to impose this change without offering grants or loans at preferred rates. This will really destroy the poultry farmers.”

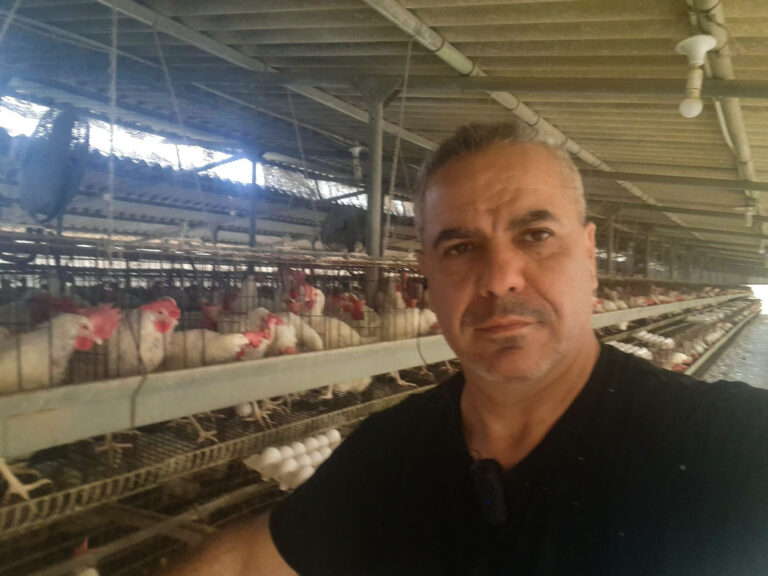

Yair Amiri (48), is also a poultry farmer and a member of the founding generation of the moshav. He says that the free range option is a big risk for farmers, that “only the big conglomerates that have bought other farms and production allotments can pull it off.”

“Where are farmers supposed to find the money to increase production? Who’s going to fund them?” Amiri asks. “Most of the poultry farmers are very old. And all this while at the same time the government wants to reduce price controls and lower the amount we earn for each egg.”

The Market: The Big Distributors’ Playground

Yekuti and Amiri are concerned by the level of control that the major distributors wield over the industry, claiming that the distributors would rather wipe out small farms and incorporate everything into larger farms.

“The big distributors will wipe out the small farmers. They have money. Whoever has money is king,” Amiri says. “It’s also a political matter for CEOs and government ministers. There are people who have a vested interest in getting rid of us. The big farms, which are also distributors, would rather buy all of the coops here and make us their employees. The whole point of this reform is to give them more power and control over the industry.”

“There’s one distributor that buys farms on every moshav but doesn’t even live there. He buys farms for their quota allotments and then combines them all into one big operation,” Yekuti adds. “They’re destroying us.”

Yekuti asserts that if he were to go work for one of the major distributors, there would be no reason to live in the remote Galilee. But he maintains that his farm is an integral part of his life and the country, and he would never give it up.

“Each chicken coop represents an entire family’s life’s work. It’s really sad that there are people who want to take that from them. If that happens, the moshav has no purpose. There’s no reason to stay here. Who will take responsibility for the Galilee?”

“We don’t want to leave. It’s also not worth it for us to leave. We’ve grown up and grown old here, where would we go? Where would we work? This is our only way to make a living,” Yekuti continues.

“The bottom line is that they’re telling farmers: ‘We don’t care about you anymore.’ When they needed us, they transferred quota allotments to the Galilee. Now all of the politicians advance their own interests at our expense.”

These farmers also also have to care for their aging parents. Their incomes are low to start with, and they have no guaranteed pensions.

“Everyone here is self-employed, so obviously there’s no unemployment insurance, Yekuti explains. “People haven’t saved up pension funds for themselves, and they’re left with nothing. They’re abandoned from every side. It doesn’t make sense, it’s not right what the state is doing. They’re leaving us high and dry.”

The Next Generation: No Alternatives

The lack of employment options in the area keeps them up at night. According to both Yekuti and Amiri, the younger generation is leaving the moshav to find work.

"If they take the chicken coops, there’s nothing left for us here,” says Amiri. “There’s no alternative here like a factory that can support people who stay here to raise their children. The younger generation is already starting to look for work outside of the moshav.”

Erez Yekuti (33), David’s nephew, married with two children, was born and raised at Dovev. From a relatively young age, he knew he wanted to live on the moshav and bought a house there. But he says that young people are thronging from the North to the center of the country, especially those who are highly educated and interested in working in industry.

“Lots of young people are asking themselves if it’s worth it to buy a farm or to invest in agriculture at all when there’s a good chance that their investment will go down the drain,” he says. “We don’t have many workplaces close to the moshav. To work a normal job you have to commute at least half an hour.”

He himself, an academic and engineer, works in robotics. He’s been in the industry for almost 10 years, and every workplace he can find has been at least 40 minutes away.

Yekuti explained that at his last job, a company developing medical equipment, he gained experience and job security, but had to leave the job when they relocated to the center, making it an hour-and-a-half commute.

“Someone like me living and working in the center of the country earns two or three times what I make, and despite that I still choose to live here,” he says.

“I think that someday I’ll be able to buy a farm here, but if the state is telling me that agriculture doesn’t matter anymore, then what is the point? We, the younger generation, we’re hanging on by tooth and nail. We want to stay in the North.”

Danger on the Frontlines

In addition to the difficulties of finding employment, there are the security challenges of living along the border.

“My four year-old son hears the music from the neighboring villages across the border in Lebanon," Yekuti says. "Every Saturday evening there are celebrations there, and I have to explain to him that those celebrations are happening in a different country, in an enemy country.”

Yekuti says that Moshav Dovev is very much the frontlines, with many unsuccessful infiltration attempts.

“We hear the announcements from the military posts next to us, the exercises, the tank engines. We hear gunfire and shelling across the border, and we don’t know what to expect,” he says.

“Even when we’re just walking through the moshav, we take into account the danger of terrorist infiltration. We know that there’s a chance that someone’s watching us from the other side. There’s a chance that at two in the morning we’ll see the skies lit up, we’ll hear gunfire and find out later that there was an infiltration.”

Erez Yekuti says there are two main reasons why he stays rather than picking up and leaving: “First of all, Zionism. If we leave this place it won’t matter anymore to Israel. And second: for my parents. When they get old I’ll need to take care of them. Even if I move to the center, at a certain point I’ll have to come back to take care of them.”

The Reform: What’s Wrong with It

According to Erez Yekuti, the reforms to the egg industry, unless they are modified, will cause damage on three levels: economic, social, and security.

Economically: No Control over Prices

“Eliminating the quotas will shatter the market. Importing eggs will shut down chicken coops, and in the end even the big distributors that control the industry won’t be able to keep up with the demand. And then, either they’ll raise the prices, or they’ll import more. It doesn’t matter how open the market is, the consumer won’t benefit. The price for the consumer won’t change. The only ones who benefit are the distributors that will get cheaper eggs. And there’s no guarantee that egg importers will charge lower prices than what we have today.

“It could also be that in a few years the prices overseas will go up, and then the price of eggs won’t be up to us, but under the control of other countries. The importer will raise the price and we won’t be able to do anything about it.

“We, the farmers, disclose the prices that we sell our eggs to the distributors for, and we’re legally required to maintain that price. Even though the price of electricity goes up, the price of corn goes up, the price of eggs stays the same. The consumers buy eggs at a fixed price that’s totally disconnected from the production costs. Unfortunately most people are unaware of this. There’s no actual need for importing eggs from abroad. There’s no reason to flood the market with eggs.

“That’s what happened with apples, for example. Until a few years ago they grew apples here. There were big orchards here. One day the state opened up the apple market. Before that people paid three shekels per kilo and got a quality, Israeli product. Today they import apples from abroad and you have to pay for the importation fees. The apples that are grown in Israel are exported. The high quality apples are sent abroad and Israelis eat apples that have been sitting in storage containers. It’s lower quality for a higher price.”

Socially: More Farmers in Poverty

“This is a needless blow to agricultural settlement. They think that the farmers are greedy, but this is a business with a very low profit margin. An 80 year-old farmer has nothing but his coop and social security. Take away the coop and he’ll be completely dependent on government welfare services, a burden to all of us. We’re shooting ourselves in both feet: we’re destroying Israeli agriculture and we’re also leaving more people dependent on government welfare as they get older.

“Besides that, I see the poultry farmers’ situation as part of the Israeli economy and Israeli society. I want Israeli consumers to understand that their interests are aligned with the interests of the farmers. Isn’t it better for us to buy fresh eggs grown in Israel? If you, as a citizen, prefer Israeli produce, you’re supporting agricultural settlement, you’re providing an income for other Israeli families, and at the same time getting fresh food for your family.”

Security: Who will Live in the Galilee?

“The scariest thing for me is to think that nobody will have any reason to live along the border. As soon as the state changes its approach and shuts down agriculture, all of the elderly people here will fall below the poverty line. Entire families will collapse. There won’t be anything to do in the North. There aren’t many retirement homes in this area. If the children have moved to the center, they’ll bring their parents there and the North will be empty.

“It scares me that the financial interests of a small group will outweigh the interest of the entire public, and that the state will compromise on the quality of our food for financial profit. We’ll pay a heavy price for this for generations to come. I love Israel and I worry about our life here.”

“They Don’t Care About Us”

David Yekuti expresses his resentment towards the country’s leaders, in the 1950’s, who sent him and his family to the Lebanon border in the first place.

“They sent us here, Ben-Gurion and Golda and Begin. Why did you send us here? What are we, your guard dogs on the border?’ We’re continuing what our parents started, and they didn’t come here for the beautiful view,” Yekuti says. “We’re like the settlements on the Gaza border. Let Israeli citizens imagine what would happen if we got rid of the farmers on the Gaza border.”

“People look at their own wallets and don’t see anything beyond that,” Amiri adds. “Their money’s not going to us. They pay a lot and we get a little bit.”

Yekuti’s despair and cynicism extends to the entire realm of politics.

“Everything is political, they don’t actually care about us,” he says. “They’re completely selling us out. You see it in health, industry, education. Politics destroyed the nation. They see us and everyone else as voters. They’re more interested in helping out the tycoons who vote for them, that fund them. We don’t have a powerful lobby, they don’t get any money from us. That’s how it is.”

Erez Yekuti adds that it is important to really ask what it is the government is trying to do with this reform.

“What interest is this reform serving?” he says. “Shutting down Israeli agriculture will just mean that someone else will profit – importers, growers in other countries. Does the Finance Ministry really want to support them and not the Israeli public? Someone will benefit from this, otherwise they wouldn’t be pushing it.”

According to both Yekutis, it is possible for the government to support its local agriculture.

“They can maintain independent Israeli agriculture and still lower the price of eggs,” says David Yekuti. “They can make it worthwhile for us to live here. They can give farmers grants to build new coops.”

Erez Yekuti adds that for him, those kinds of grants are a basic expectation to keep production inside of Israel.

“I work in technology. That’s the answer for agriculture as well. If the State of Israel is interested in protecting workplaces and maintaining independence and control over prices, it needs to offer technological development grants for agriculture,” he says.