Late last month, Arab communities across Israel commemorated Land Day, a day which has become symbolic of the Arab struggle against discrimination and persecution. Davar sat down with sociologist Aziz Haidar to discuss the history of the day and its meaning for today’s Arab communities.

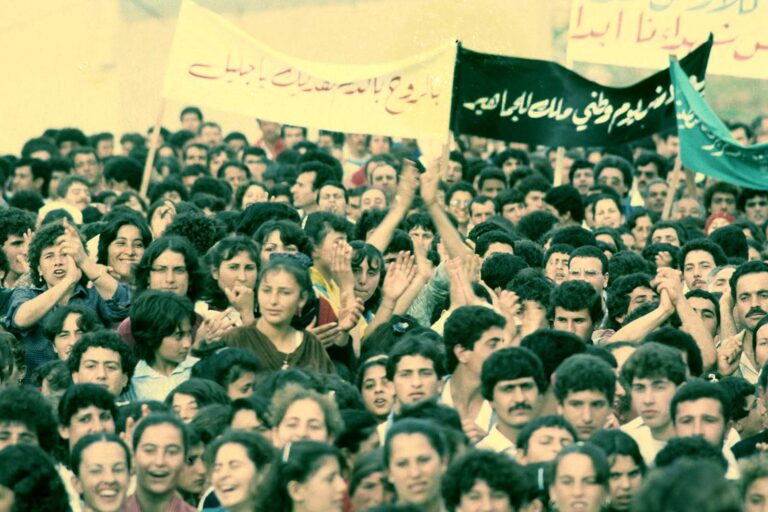

Land Day commemorates an Arab uprising in 1976 against expropriation of land in the Galilee region for use by the state. During the protests, six Arab Israelis were killed by police forces and around a hundred others were wounded. For Haidar, this day represents an important development within the Arab public since the establishment of the state of Israel – the maturation of the Arab political consciousness and the development of an Arab leadership that operates within the rules of democracy. Haidar explains the demonstrations of 46 years ago as a turning point, the effects of which one can trace all the way to the entry of an Arab party into the governing coalition last year.

“The Land Day demonstrations of 1976 symbolized on the one hand, the value of the land and the great need for land in Arab communities, and on the other hand, the development that’s taken place in Arab society since the establishment of the state,” says Haidar, a lecturer in sociology at David Yellin College and a research fellow at the Van Leer Institute and Hebrew University’s Truman Institute. “This happened at a time when there was momentum in Arab communities, and a drastic change in education, the economy, and especially in the political sphere.”

Contextualizing Land Day

“The 1970s were a defining decade for the Arab population,” Haidar said. “Almost all areas of life had completely changed. This happened at the time the were beginning to change their minds about the state of Israel. They went from survival to acclimation. From a civilian point of view, the military government was abolished and they were no longer subject to the military. Economically, the entire Arab labor force was integrated into the labor market, and unemployment in Arab society was approaching zero. It created tremendous economic development.”

But the issues surrounding Arab land ownership cast a shadow on these developments within Arab society. In the 1970s, the government began expropriating agricultural land that belonged Arab citizens in the Galilee in order to establish Jewish settlements, the largest of which was the city of Karmiel. Arab Israelis expressed their anger regarding the plan through political action. In the first time since the establishment of the state, a general strike was declared across Arab communities. Activists also held demonstrations that were violently suppressed by the police and the military, leading to the death of six Arab civilians.

“Land Day was a period of political momentum,” Haidar explained. “What made it successful was collective action, which had not existed in Arab communities at the time. This was the Arabs’ first collective action. It was revolutionary.”

Haidar emphasizes the central role of Arab students in the uprising.

“The Arab student committees were very strong. They had intense daily activities. Their part of the protest was very large, and was more prominent than that of the Arab parties, which were not developed at the time. There were only two political groups then,” he said. “On the eve of the strike, the Committee of Heads of Arab Authorities did not have a majority [in favor of action]. Those who tipped the scales were the students, who came in hundreds for meetings.

“Another figure who played a key role in the struggle was the mayor of Nazareth, Tawfiq Ziad, who before being elected mayor was a member of the Knesset for Rakah, the Communist Party,” Haidar said. “It’s impossible to forget Ziad’s leadership. As a longtime leader, he was able to bring this about. There was a combination of appropriate leadership, social and economic conditions, and student activity.”

When Haidar looks back on developments in Arab Israeli society since the first Land Day in 1976, an element that stands out is the weakening of the Arab student body as a distinct political actor.

“As the parties grew stronger, the share of students in political activity declined. Starting in the 90s, you no longer see their activity the way it used to be. It was a phenomenon that’s never been repeated. The students are inactive because there are parties. This was institutionalized activity within the framework of existing law alongside the phenomenon of integration into the Israeli political center,” he said.

Since the 1970s, this process of Arab integration into the Israeli political and economic world has been evident. Haidar traces this history to the groundbreaking event last year when the Islamic party Ra’am became the first Arab party to sit in a coalition.

“What is happening today with Ra’am entering the coalition is not a new idea,” Haidar said. “As early as the 1980s, the progressive [Arab] movement said, ‘we are an integral part of the Israeli political center, and want to be part of decision making.’ The progressive movement holds the concept of ‘a state of all its citizens.’”

Arab despondency and Its consequences

After the first Land Day, it took the Arab public another 24 years to return to mass protests. In October 2000, Arabs put on demonstrations protesting the visit of then-opposition leader Ariel Sharon to the Temple Mount, a contentious holy site for Jews and Muslims alike. Nine Arab civilians were killed in clashes with the police during those protests. Haidar points to these events as another turning point, one which has weakened the leadership of the Arab public as and reduced its political involvement.

“The Arab leadership can no longer mobilize thousands for a protest the way it once could. Since 2000, the Arab leadership has been afraid to utilize public outcry from the entire public,” Haidar explained. “Meanwhile, the political participation of the Arab public has receded. The Arab public no longer believes in this kind of protest because they don’t have faith in the leadership. In the October [2000] riots, Arabs discovered for the first time that they were not really citizens. A sense of alienation and despondency began, something that’s hard to explain. They realized that there was a clear failure regarding relations with the state.”

Haidar notes another important point in the relationship between Arab Israelis and the state: the publication, in 2006 and 2007, of a series of documents entitled “The Future Vision of the Palestinian Arabs in Israel.” These documents called to define Israel as a Jewish and Arab state, to give Arab citizens more resources and more substantial roles in government and decision making, and to recognize the Nakba, the Arab phrase for the Palestinian displacement during the 1948 war.

“The documents were written by academics and activists from various groups, especially independents, after a period of despondency. They have some disconnection from the Palestinian problem,” Haidar said, referring to the issues facing Palestinians living in the occupied territories.

The documents were not approved by the Arab Higher Monitoring Committee, a civic body representing Arab Israelis, because of opposition from the Northern Islamic Movement and the secular Balad party. In response to the documents, representatives from Balad wrote the Haifa Declaration, which emphasizes the Israeli Arabs’ connection to the Palestinian people and to the Palestinians in the West Bank.

The years after the publication of these vision documents were characterized by an accelerated integration of Arab Israelis into the labor market, which coincided with processes of increasing neoliberalism within the Israeli economy as a whole.

“Prime Minister Olmert changed his policy to promote the integration of Arabs into the labor market, together with the advancement of Israel’s neoliberal regime. Netanyahu continued this policy,” Haidar said. “He said that it was wrong to discriminate on the basis of nation or religion, and that deep integration was needed and that it might even bring about equality. He promoted integration into the labor market, but not integration in the economy, and promoted extreme political exclusion.”

The role of political parties and nonprofits

“When Netanyahu’s power was ebbing, he legitimized Ra’am, and eventually brought Ra’am into the coalition,” Haidar explained. “The Jewish parties were afraid to work together with the Arab parties. The Arab parties twice recommended Gantz as prime minister, but he was a coward. Only Netanyahu could legitimize the Arab parties. He legitimized Ra’am, the other parties legitimized everyone. It is a process that needs to be investigated – on the one hand, being excluded from the political process, and on the other hand, entering a coalition.”

Although the main factor in the exclusion of Arabs from the political leadership is the opposition of Jewish parties to Arab influence, Haidar thinks that Arab parties also play a part in this dynamic.

“I would argue that some Arab parties want exclusion, in order to secure the Arab votes, and to prevent support for Jewish parties. Since 1996, more than 80% of the Arab vote goes to the Arab parties. It’s an electoral ghetto that serves the Arab parties,” he said.

Another substantial change is the flourishing of civil society organizations, which Haidar says are also a channel for political action.

“Arab civil society organizations have never been apolitical,” Haidar says. “They gained a lot of strength after 2000, with the weakening of the parties, and their role greatly expanded. Not only has the number of nonprofits has increased, but the major organizations are also trying to become closer to the parties. A large part of them are affiliated with certain parties.”

Haidar is critical of these organizations, which in his mind do not fill the leadership gap in Arab-Israeli society.

“There are outward facing rather than inward facing. They are about relations with the state, not internal change,” Haidar said.

“Lately, most heads of nonprofits want to make their way into politics,” he continued. “At the last election, I counted 13 senior nonprofit executives trying to get into the parties. They will become the next generation of leadership only if they set up new political frameworks. The existing parties are closed. If they want to fit into politics, they have to start new movements. The question is whether they're going to succeed at that.”

Haidar predicts that the issue of the land will remain central to the Arab political struggle within Israel, notwithstanding the many changes in Arab-Israeli society.

“The land will always remain at the heart of the struggle. Conditions were different then, but the effects of land expropriation are constantly getting worse. There is no land reserve in Arab society. There is nowhere to build houses, gardens, businesses, industry,” he said.

“The problem is bigger than it used to be, and it will continue that way because the policy hasn’t changed,” Haidar explained. “There is always talk of expropriation, but the state has actually annexed Arab-owned land to Jewish regional councils. About fifty percent of land owned by Arabs are now under those same regional councils. This process started in the 1960s and continues to this day.”

Haidar condemns the lack of intervention on the land issue by Arab members of Knesset.

“The politicians are silent,” he says. “The problem is there’s no proper political activity. The development plans don’t address it. I’m critical of the fact that the Arab political world doesn’t dare talk about it. It’s almost 300,000 dunams [75,000 acres] of land. If some of this land had been released, and with proper planning, all this concern would have been solved. The result is that the Arabs must build without a permit. The state charges billions every year, and the politicians refuse to address it.”

Individual vs. collective integration

Another consequence of the land shortage is the migration of young people and Arab families to Jewish communities or mixed cities. For Haidar, this is a worrying phenomenon.

“The ones who move are the most educated, the prestigious professionals, those who might have set an example and created change within the Arab communities,” he said.

Haidar does not understand this phenomenon as an expression of Arab integration into Jewish society.

“It’s forced integration. They’re moving because there is no housing and work in Arab communities, and the quality of life is intolerable,” he explained. “Eighty percent of those who move talk about quality of life. The question is whether I have alternatives I can choose, or do I have no alternatives and I have to leave.

“The quality of life in Jewish communities is totally different, although sometimes the distance is no more than one or two kilometers. In some areas in the north, people are moving to Karmiel. They work in the [Arab] village but live in Karmiel. The children go to school in the village, and in the afternoon, they return to Karmiel. The mobility is backwards,” Haidar explained.

“Moving results in a personal, individual integration,” Haidar added. “That’s not new. The problem is the collective integration. As a community, the Arabs remain on the outside of society, to this day.”

This article was translated from Hebrew by Leah Schwartz.