Part of the idea behind Zionism and establishing the state of Israel was to create a sustainable environment for Judaism outside the shul, and outside the religious realm. Just as many Israelis find it difficult to see the various non-Orthodox denominations in Judaism as a vibrant, creative path in the Jewish joint heritage, many non-Israeli Jews do not see secular lifestyle in Israel as a Jewish denomination. Well, it's not exactly a denomination because it does not treat Judaism as a religion, but rather as an identity, nationality, culture, peoplehood and heritage. But we'll treat it as a stream anyway.

Halachic law, in any denomination of Judaism that sees itself as a religion (be it Reform, Conservative, Reconstructionist or ultra-Orthodox) aims to create a holistic, intensive and sustainable framework that shapes a community, shared values or faith, and a joint culture. There for every Jewish community around the world would like to have a place to meet together and celebrate meaningful days in the Jewish calendar, Hebrew school that teaches kids the basics of their roots and heritage, a kosher shop, a place that serves Jewish food, burial services and so on.

Well, in Israel all this happens on a national scale. That's why it's called the Jewish state, after all. It just means that the arguments about how everything should be run, and we know that arguments are a big part of a Jewish community, are also on a national level.

Of course, the education system plays a major role in this. Israeli schools, even secular ones, teach mandatory classes that deal with the history and culture of the Jewish people. School holidays are decided according to the Jewish calendar, and the biggest revolution of all is that it’s all done in Hebrew. One joint language we once used only for prayers. Most Israelis would say that this has nothing to do with the Jewish religion. "It's our traditions, that's all."

To a large extent, every debate, every interpretation or conflict about Judaism in Israeli public life, eventually reaches the classroom. The political debate on religious indoctrination, or 'Hadata', at school is focused these past few years on a subject which is taught throughout the Israeli school system, both religious and secular – Bible studies.

Bible studies is also a Zionist revolution. Traditionally, in Exile, Orthodox Jews studied Talmud and Mishna, but in Israeli schools Bible studies were made mandatory. For obvious reasons: in contrast to the Talmud, the Bible happens mainly in Israel and portions of it deal with a sovereign Jewish entity in the Promised Land.

Over the years, growing portions of the secular Israeli public have begun feeling that this subject has been steering further and further away from their values, sometimes for politically motivated reasons. This, in turn, has created more distance and sometimes even outright rejection of a subject which was not easy to teach or learn in the first place: The language is archaic, there are no perfect heroes and not that many happy endings.

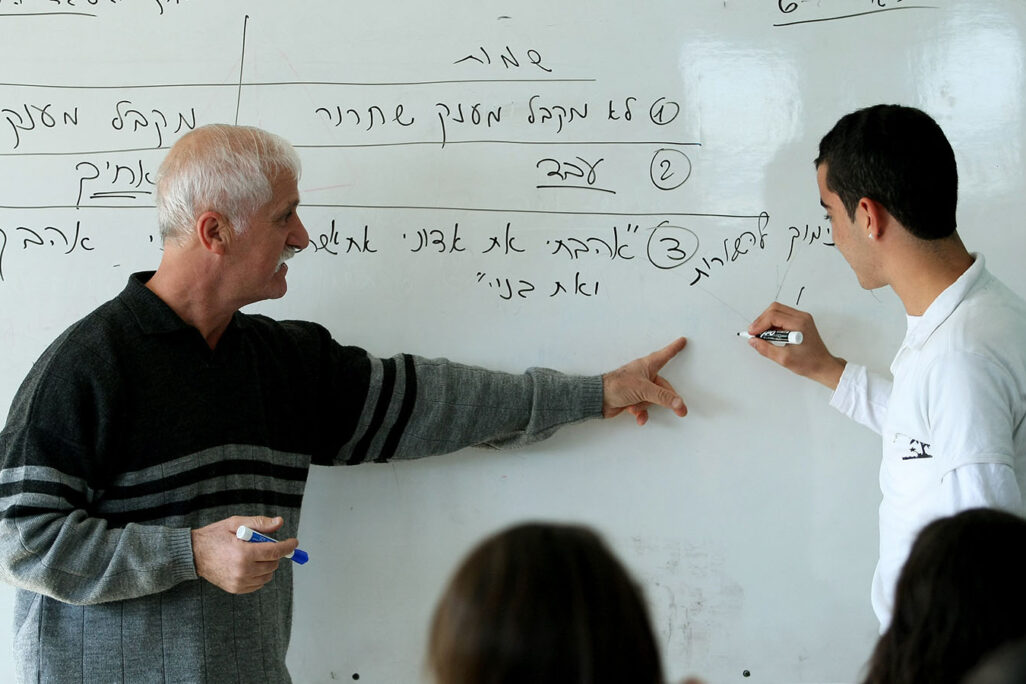

In the end of the day, the people who enter this hazardous minefield are the teachers in the classrooms. How do they do it, and why? Three Israeli teachers from different backgrounds and different worldviews told us about their choice to continue their work in Bible studies, and demonstrate that this field is not only relevant, but belongs to each and every one of us.

"Finding the core values"

"As an adult, through no fault of my own, I was not exposed to many key Jewish figures and stories, which I am only discovering now at the age of 41," said Lior Oz, a Bible teacher at Bereishit Elementary School in Binyamina.

"That's how it is, there are many things that a regular secular school doesn't teach." Oz, a married father of three, defines himself as a traditional-secular Jew, and has been teaching Bible for nine years at the school, which integrates religious and secular students. He sees his profession as both a calling and a chance to make up for lost time.

"Judaism doesn't belong exclusively to the Orthodox or the ultra-Orthodox, it belongs to everyone. Why shouldn't I be knowledgeable and understand my identity? Because someone decided on my behalf?" said Oz.

He claims never to have heard the phrase "religious indoctrination" while growing up in Lod. During his school years, he and his classmates took mandatory Bible classes, young people went to different synagogues and the whole experience stands out to Oz as a positive one.

"I think that what happened over the years is that the public-religious school system carried the flag, because that was what they were used to at home and in their lifestyle, and the secular side went to the other extreme and said: wait a minute, this whole thing which entered the secular school system – it's religious indoctrination."

Important to explain here that there are public, Hebrew-speaking, secular schools (43.3 percent of students); public, Hebrew-speaking, religious schools (13.8 percent of students); and Public Arab speaking schools (24.5 percent of students).

"Among secular people there's often ignorance and closed-mindedness, but I'm naturally curious," said Oz, who is active in a group called Israeli Midrash, in which religious and secular people study Torah together. "My town, Charish, is a great example of living together well. You have religious and secular people living in the same buildings, and there are no separate neighborhoods. Maybe secular people are scared of the implications on their daily lives, or think it will impact their children's lifestyle. Just like religious parents fear that if their children play with secular children, they will discover a different world."

So what do these classes actually look like? Torah classes are held for religious and secular students together, and each student brings their own perspective. It's not easy for everyone, said Oz, and adds that some of the religious students complain that there is not enough Judaic study, while some of the secular students complain that there is too much.

"We have Bible, Talmud, the weekly Torah portion and Israeli Jewish culture – that's much more than you would find in a regular secular public school. How do we deal with this? We as the teaching staff try to find the right balance. Our Bible classes involve reading aloud. Every child reads a verse, or we do a theatrical performance," said Oz. "I bring the kids face to face with the text, after every story we try to define the key values and I ask how it's relevant to them, often using interactive methods. For example, we read the Song of the Sea [one of three poetic sections of the Torah, which tells the story of the crossing of the Red Sea – D.T.] and we discuss avoidance. When the children of Israel leave Egypt they don't travel through areas where the Philistines dwell, but take the long route and avoid them. When someone's bothering me and annoying me, do I choose confrontation or do I choose to avoid them?"

"I think that the Minister of Education needs to leave Bible studies as they are," said Oz, relating to latest statements on the topic by Rabbi Rafi Peretz. "Of course he needs to express his opinion and it's his right to do so. But this process needs to happen differently, through teacher training programs and through the educational staff – it shouldn't be imposed from above. It can happen through events that the Ministry initiates for students. Many teachers, myself included, think that we need to deepen our knowledge of Jewish content, but when you make public declarations you should expect a backlash, especially at a time when this subject is a pressure cooker at a high temperature."

"We mainly teach stories here, not necessarily history"

"We're talking about an ancient creation whose language is essentially nonexistent today. It's like teaching Shakespeare in the original English- it isn't easy. The images and the language are completely different and you need to constantly interpret," said Achik Gofer, a teacher and director of Bible studies and Jewish philosophy, who has served in this role for over 20 years at Asif Misgav Secondary High School. "That's why some people don't understand why it should be studied in regular secular schools. There's built-in antagonism."

Gofer comes from a secular background and defines himself as secular. He said he was a pretty bad student. He finished high School with no diploma and, until he began supplementary studies after his army service in order to gain a diploma, he remembered school as a traumatic experience which he never wanted to go back to, certainly not as a teacher.

"After the army I understood that nothing would work out for me without a matriculation certificate, so I signed up for supplementary studies and I discovered that I enjoy learning."

While he was there, he met a teacher who caused him to look at Bible studies completely differently, and unleashed an urge to study – and to teach.

"There are people who look at the Bible and see pages with words written on them, there are people who hear it like a radio broadcast and those who view it like a movie. I see the Bible as a three-dimensional movie – I understand it very deeply," he said.

"We mainly teach stories here, and not necessarily history," Gofer explained in relation to the challenges in teaching Bible today. "There are so many layers that you need to relate to. We're talking about a creation which will be eternally controversial and political. I don't know many subjects in life that when you want to teach them, you know you're walking into a minefield and you need to cross it safely."

History, literature, philosophy, legislation and politics, all in one book.

Gofer's educational philosophy is that getting past the many obstacles which this profession presents for secular school teachers means understanding that we are working with a human creation.

"That's true for a work that was written 3,000 years ago, for a work that is being written today or one which will be written 2000 years from now. The Bible is a human creation in which God appears as a superhuman figure, and this is our starting point. The human soul is an ancient one and when a person in ancient times fell in love it was the same as someone today – they felt the same butterflies in their stomach, the same longings – they just wrote about them differently," said Gofer. "From the beginning I knew that the initial response to this subject has to come from an emotional place, through experience, and not from a didactic place, because otherwise it won't work. You might memorize the Bible for your matriculation exam – but you would never love it."

In his classes, and especially the classes for students who choose a track of additional Bible studies and Jewish philosophy (Asif Misgav is the only high school in Israel which offers this track), many different methods are used. In exercises and homework which he assigns the students, he requires them to bring examples not only from the Bible, but from their own lives, including from music and literature that they know.

"It works – students learn to see the Bible differently," said Gofer. "It's not some book for religious people, and it's not any old history book. It's a book about feelings, it's a time capsule and a black box which reached us miraculously and it's deep, philosophical, but also very much emotional."

In 10th grade, the students learn about good and evil in Jewish thought and the Bible, and they also discuss life today. And in 11th grade, the students spend an entire year learning about love and romantic relationships via the Songs of Songs and additional Biblical texts.

"The students drink it up because that's exactly what they need at this point in their lives," Gofer points out.

"There's politicization seeping into the two education systems [secular public and religious public – D.T.], each of which works in its own way and neither of which is superior to the other," said Gofer, criticizing the political use of the subject over the past few years: "Using Bible studies for political ends causes one side to feel like the subject isn't necessary or that there's only one way to teach Bible. My students ask me almost every year how can I teach Bible if I'm not religious. I call this secular ignorance, and I think it's very sad – this book has brilliance and beauty which are completely separate from any religious-secular issue."

"Finding connection from a place of dialogue"

"Today Bible studies in Israel are seen as belonging to religious people, and this causes a large part of the population to feel that the Bible doesn't belong to them," said Timna Linden, a Jerusalem native and resident.

Linden has been teaching Bible studies at Hebrew University High School and Junior High for six years.

"The Bible is a complex text which contradicts itself and is made up of different versions of various stories, of different worldviews and, of course, of different commentaries. This understanding allows me to bring my own commentary and to invite everyone to find their own meaning," she said.

Linden, who comes from a Conservative Jewish background, chose to study in the Revivim Program of Excellence for Training Teachers in the Instruction of Jewish Studies, because she saw teaching Bible as a calling.

"I was raised with the idea that you can choose your own path, but you need to choose based on knowledge, not ignorance. I went into the program in order to form my own dialogue with the Biblical text," Linden said. "The dialogue I want to have is critical. It will have disagreement but also learning. You must understand that this text is much more complex than how it is typically presented."

One of the difficulties which many teachers probably won't want to admit is that the subject is less desirable for most students, compared to mathematics or English (as a second language), and getting students interested is a challenge in itself.

"I teach seventh grade, and they bring a lot of resistance to this field which carries over from elementary school. Let's just say that most of them would say that Bible, Jewish studies and Israeli culture – all of them compulsory today, are not the subjects they are most interested in learning," said Linden.

"I try to expose them to a different style of studying the text and mainly, I think my biggest aim is to give them tools to relate to the text on their own and to see that there are a thousand ways to interpret every piece of it,” she added. "I always tell my students that it's less interesting whether the stories there actually happened – it's a book which is a cornerstone of the culture we're a part of, and literature which was written much later is also hard to understand without this basis and background."

For 12th grade Linden teaches the story of the destruction of Israel and Judah and shows how many different texts tell this tragic story from various perspectives.

"We study the books of Kings, Chronicles, Isaiah, Jeremiah and each one of them affords a different vantage point towards the question of why the First Temple was destroyed. One view said that the king was a sinner and the nation was punished for the sins of the king. Another said that it occurred because of the nation's sins. The Bible does not have a consensus on this topic and that's because it's not about trying to describe the destruction of the kingdom of Judah objectively, but rather about conveying an educational message that teaches the worldview that underlies the writing of the text," said Linden.

"If a teacher comes into the classroom and said that we're studying a sacred book written by God and every word in the book is absolutely true, this automatically creates a barrier for the students. You can't force anyone to learn a specific meaning or worldview just because someone decided."

Linden thinks the discourse of indoctrination is harmful to both sides, and not only the religious side harming the secular one – it's making it harder to fulfill one of the most important aims of Bible studies, creating a shared basis for life in Israel.

"The discourse of us-versus-them is bad for Bible studies. Both sides need to try harder for unity. I believe that all sides want something good, but the key here is to allow a variety of voices and streams,” Linden explained. “Israeli society needs to focus less on defining for other people what's right and wrong, and more on allowing everyone to find their own connection, or lack of connection, through dialogue."