What does Chanukah tell us? What are we even celebrating? Are we marking the military victory of the Maccabee rebel leaders over the Greek tyrants? Is the holiday really about the tiny jar of oil that miraculously lasted for eight days, enabling the Jewish victors to resanctify the Temple after recapturing it from the Greeks? Or are we just marking the winter solstice by lighting candles and stuffing our faces with sufganiyot, the jelly donuts readily available for purchase all across Israel for the holiday?

Like many other Jewish holidays, the manner in which Chanukah is celebrated has changed over the generations, and its content has been determined in accordance with the various forces attempting to educate and lead the way forward for the Jewish people. Jewish ideological wars fought over Chanukah have included boycotts, strictly adhering to phrases from the Mishnah, renewing historical values and even writing children’s songs.

It all started with a rebellion

The classic Chanukah story told today, based on the Book of Maccabees, takes place during the rule of Antiochus IV, a Hellenistic king who sought to stamp out Judaism by issuing decrees forbidding Jewish practice and turning the Second Temple in Jerusalem, then the vital center of Jewish ritual life, into a Greek sanctuary. When Mattathias, an elderly Jewish priest and a fierce Jewish purist, was ordered by a Greek officer to offer a sacrifice to the Greek gods, he refused and proceeded to kill the officer and a Jew who agreed to make the sacrifice in a dramatic showdown.

Mattathias then fled with his five sons to the wilderness. The next year, the five Maccabee (Hammer) sons, led by brave Judah Maccabee, led a gruesome guerrilla revolt against the Greeks that succeeded to recapture the Temple and restore religious freedom for the Jews. Later rabbinic sources add that when the victorious Maccabee rebels re-entered the desecrated Temple after recapturing it in the revolt, they needed to re-purify it by burning purified olive oil, but the stores of oil had been destroyed. Miraculously, a small bottle that survived the destruction lasted the eight days needed to produce a new batch of purified oil.

Replacing the lost Sukkot and re-establishing the Temple

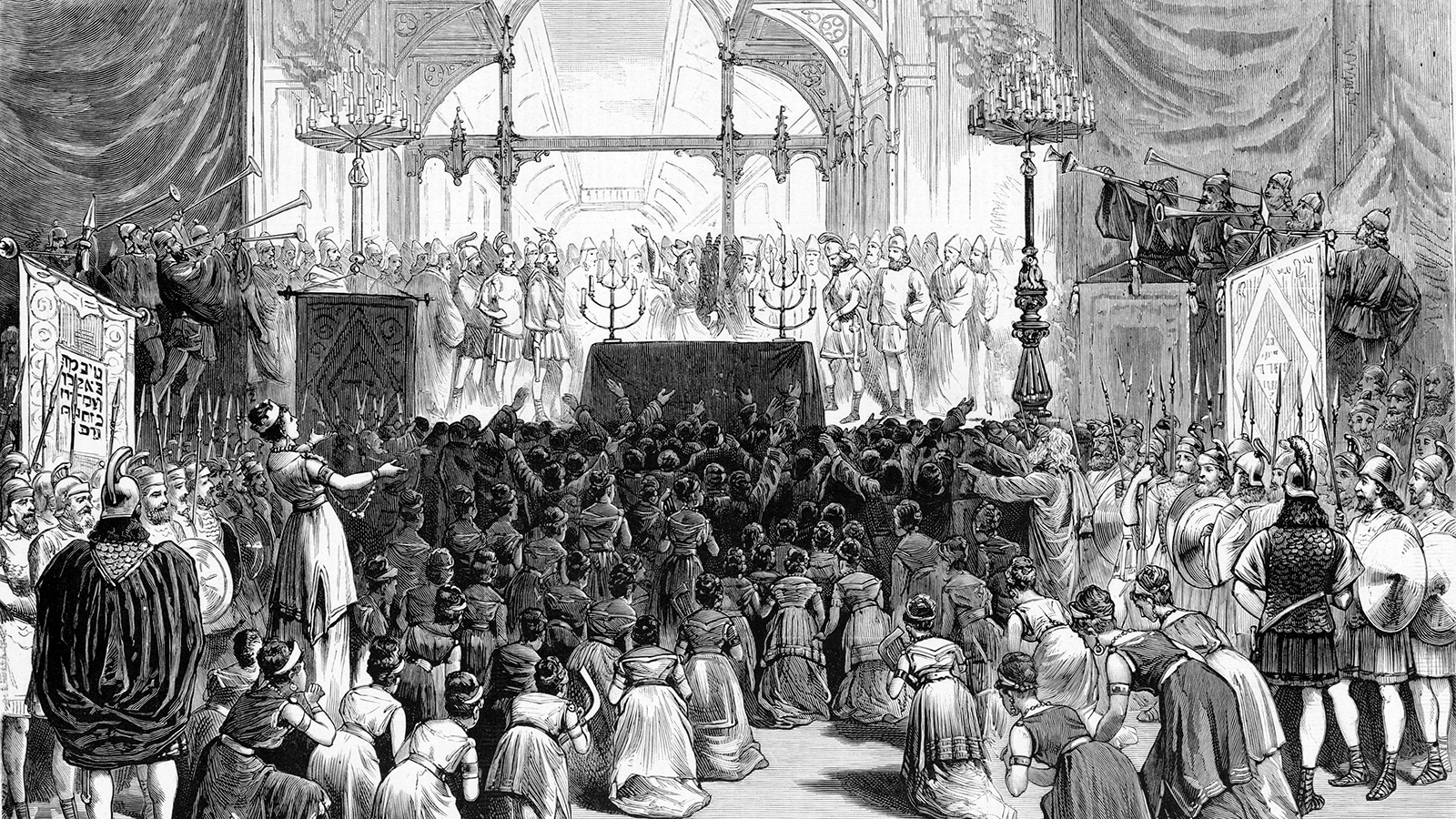

The first interpretation of Chanukah was provided by the Maccabees after liberating the Second Temple from the Greeks and their assimilated Jewish partners around the year 160 BCE. In a letter sent by the Maccabees to their brothers in the diaspora (primarily in Alexandria), they request establishing the holiday as a joint day of remembrance for all of the Jewish people, and as a kind of replacement for the holiday lost two months prior that they could not celebrate until the Temple was liberated: Sukkot. As described in the letter, after liberating the Temple, the sons of Mattityahu and all who were with them purified the Temple and renewed the sacrificial tradition.

As soon as the Jews were liberated from the injustice of the Greeks, they could finally celebrate a kind of replacement for the holiday. As written in II Maccabees (10:6-7): “6 And they celebrated it for eight days with rejoicing, in the manner of the feast of booths, remembering how not long before, during the feast of booths, they had been wandering in the mountains and caves like wild animals. 7 Therefore bearing ivy-wreathed wands and beautiful branches and also fronds of palm, they offered hymns of thanksgiving to him who had given success to the purifying of his own holy place. 8 They decreed by public ordinance and vote that the whole nation of the Jews should observe these days every year.”

But the Maccabees don’t stop at justifying the new holiday as a replacement for Sukkot. They ask their brothers to celebrate with them as a commemoration of an ancient miracle which brought about the establishment of the Second Temple, and to connect the purification of the Temple and its liberation in their times to its very construction. II Maccabees (1:21-33) tells the story of Nehemiah, one of the leaders of the Shivat Zion movement to return to the Land of Israel from Babylon, who knew that when the First Temple was destroyed and the Jews exiled, the priests (Cohanim) hid the eternal flame of the altar somewhere in the Temple.

Nehemiah asks the priests’ descendants to search for the fire left by their ancestors. The priests find only frozen water in the dry cistern, but Nehemiah doesn’t despair. He collects the water and brings it to the altar. When the sacrifice and firewood is ready, Nehemiah throws the frozen water onto the sacrifice and the firewood. Then the clouds part and the sun comes out, and the wood suddenly bursts into flames, thus reigniting the eternal flame of the altar, with the entire nation bowing down in prayer until the sacrifice was fully burned.

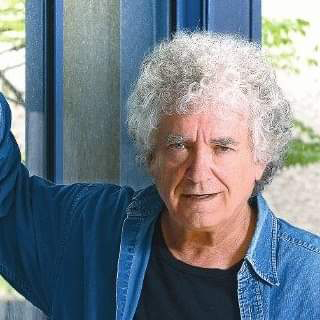

“In our time, we suffice with the miracle of the oil, but for the Maccabees, whose writings were removed from the traditional canon and were forbidden to read, a much more significant miracle occurred,” says Ari Alon, a secular biblical interpreter who teaches at the Chagim Center, BINA and the Shalom Hartman Institute. “Here they created a connection between the re-purification of the altar and the return to sacrifices in the Second Temple by Nehemiah. For them, there was an eternal flame preserved as frozen water, wood, sacrifice – the entire nation witnesses this. That’s some miracle.”

“Why do they send this letter and try to market the Chanukah holiday? They describe the victory over the Greeks, the return to sacrifice at the altar, and also compare the miracle that God performed for Nehemiah with the miracle that he performed for them in conquering the Temple. They are demonstrating the power of divine intervention, that God helped them liberate the Temple just like he helped Nehemiah,” said Alon.

Since the days of the Maccabees, the holiday has undergone a number of changes, and has been the subject of many arguments between different groups and streams within the Jewish people. “There were a lot of fights, even within particular streams," clarifies Alon. It’s not simple or consistent. There are all kinds of power struggles and political struggles, even within what can be called ‘the different sides’.”

Where did the Maccabees go?

A significant change in the narrative was cemented when the full story of the Maccabees – also known as the Hasmoneans – was edited out of the canon. It might be due to the fact that although they fought the Jews who assimilated into Greek culture, in the end the Hasmoneans themselves assimilated as well. The grandchildren of Judah the Maccabee and his brothers used Greek names, and Yehudah’s brother Jonathan even took the double title of high priest and king – something which had never been done before.

“I am yet to find a thorough and intelligent enough explanation as to why their story has been hidden like this,” says Alon. “But it’s also related to certain difficulties with the Hasmoneans – with what became of them. The generations to follow assimilate into Greek culture. There are also political rivalries here. The Pharisees and the Rabbis are threatened by them.”

The books of the Maccabees were not included in the Jewish Bible, along with other books which together are called the Apocrypha.

“I completely understand why they oppose other classic Apocryphal books, such as the Book of Jubilees,” says Alon. “The book calculates the holidays by the solar calendar, rather than the Jewish lunar calendar. But this is not the case with the Hasmoneans and the heroism of the Maccabees. It’s clear that they had a major fear of rebellions, just like they had a negative reaction to Bar Kochva, who they called a false messiah.”

This kind of moderation, with a much more modest miracle, without human rebellion or heroism, in a similar vein to the absence of Moses in the Passover Haggadah, focuses the story on the actions of God. Come to that, even God is shown only in a small miracle of oil lasting longer than expected, instead of a serious miracle with frozen water turning into fire. Is this an attempt to turn down the heat? Alon thinks that it definitely could be.

"Even in the Talmud there is a tension between very serious messianism and those saying ‘There is no messiah in Israel’ – he existed in the past and will not return. This corresponds with the fact that they refuse to rebuild the Temple even when they have the opportunity. They write that studying Torah is greater than building the Temple. Studying Torah is the new sacrifice at the altar. This is a process that turns studying Torah into the holiest act," Alon said. "The sages wrote, ‘A Torah scholar of illegitimate birth is greater than an ignorant high priest.’ They are definitely in conflict with the priests and the preeminence of the altar and so on. But it’s not easy, because even among the sages there were those who wanted the Temple, so it’s also an internal conflict.”

Alon describes a process that preserves the yearning for the Temple and the return to the Land of Israel, but as a dream for the future that is not actually expected to be fulfilled, and that is even forbidden to plead for in prayer. This is in essence an attempt to control the messianic feelings of the Jewish people, and even the commitment to go back to the Promised Land, but not to uproot them entirely. "Next year in Jerusalem". Next year, but never this year.

When was the oil jug “discovered”?

The holiday develops and changes through the centuries, and the Babylonian Talmud’s Sabbath Tract includes a discussion about the manner in which Chanukah candles should be lit: either one for each member of the household, or one candle for the entire household. There’s also a request to place the candles in a public space that is visible from the outside, as well as the more well-known argument between Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel about whether to start with eight candles and remove one each night, or to start with one candle and add one each night.

But the real innovation in the Babylonian Talmud takes place in the story explaining what Chanukah is – the first time in which the story of the oil lasting eight days is introduced to Judaism. “For the Greeks entered the Temple and they defiled all of the oil in the Temple, and when the Hasmoneans prevailed, they looked and didn't find anything but one flask of oil that was stamped with the high priest's seal. And there was only enough to light for one day. And a miracle was made and they lit for eight days. The next year they established these days as holidays, for the recitation of the Hallel and for Thanksgiving.”

What’s new here? Or better yet, what’s missing here? The story of the Maccabees liberating the Temple has disappeared, making room for the miracle that happened after the liberation, which created the conditions to restart its rituals. Just as Moses is missing from the Passover Haggadah, this version of the holiday’s story skips over the human figures and their rebellion. The Babylonian Talmud was written between the 3rd and 5th centuries before the common era – at least 450 years after the Maccabean rebellion. What transpired in the intervening years that so drastically changed the contents of the holiday?

We are familiar with the Bar Kochva rebellion in the year 132 CE, but there were also a few smaller rebellions prior to this one, both in the Land of Israel and in various diaspora communities, all against the Roman empire. It doesn’t end well: the history books of the era include horrendous descriptions of rivers of blood flowing into the Jordan river and processions of exiles being taken into slavery.

Surviving Exile

One of the strategic decisions made by the Jewish people in order to survive was to avoid drawing too much attention to themselves. They would preserve the faith, various traditions, and the unique essence of their people by enacting a change in Halacha (Jewish law) that would slowly but surely ensure that the Jewish people would survive. Surviving has two aspects: on the one hand, they would not be murdered in their entirely due to their weakness in exile, and on the other hand they would not be assimilated into the nations among which they dwell.

In order to create and preserve this reality, the rebels and rebellions had to be taken out of the lexicon. The Books of the Maccabees were not included in the list that would make it into the canon of the Jewish Bible, but rather were incorporated into the forbidden Apocrypha. Reading these books was strongly forbidden, and some even claimed that those who read them would lose their place in the “world to come” (the Jewish conception of heaven).

Zionism revives the Maccabees

With the rise of Zionism as the Jewish national liberation movement, the heroism of the Maccabees became a subject of interest and inspiration for Zionist leaders. The founder of the Zionist movement, Theodore Herzl, concluded his book The Jewish State with the words, “Therefore I believe that a wondrous generation of Jews will spring into existence. The Maccabeans will rise again.” In the poem “They say there is a land,” Zionist poet Shaul Tchernichovsky imagines meeting Rabbi Akiva and asking, “Where are the holy people? Where are the Maccabees?” Akiva answers him, “All of Israel is holy. You are the Maccabee.”

Another leader who renewed interest in the Books of the Maccabees was prolific Hebrew poet Hayim Nahman Bialik. Ari Alon points to a speech made by Bialik on the 25th anniversary of the founding of the Jewish National Fund on Chanukah 1927, in which Bialik laments the absence of the Books of the Maccabees from the Jewish Bible and the fact that they are preserved only in Greek by the Church. He argues that reinserting the story of the heroism of the Maccabees into the Jewish ethos would bring about a renewal of the national spirit of the Jewish people.

“All of the events surrounding the redemption will be connected to this national holiday… Not only to remember the Maccabees, but also to remember the noble zealots, whose names have been erased from our history,” Bialik said. According to him a shared ethos, including the sustained yearning for the homeland, even though it was maintained as a longing devoid of clear manifestation, would undergo renewal and inspire the Jewish people.

“With our final redemption we shall redeem all of our efforts – those that succeeded and those that did not – we will revive them, make space for them, and they will fill Chanukah with new meaning. And we will understand the value of these little things that connected us and clarified the scent of the earth and the sense of the homeland in our souls, and acted on us and caused us to bring about the redemption of the Land of Israel,” Bialik said in his speech.

Alon notes that some fifteen years after this speech, Bialik suggests that Chanukah be renamed the “Day of Redemption.” Alon said that Bialik wanted it to be known as “A kind of Independence Day, a magnet attracting all of the stories of redemption. The opposite of the 9th of Av.”

Biliak’s Zionist approach is a direct assault on the traditions and understandings cemented in exile, which emphasized the divine miracle.

“You can compare the words of the traditional Chanukah song “Mi Yimalel”: ‘In those days at this time, the Maccabee the savior and redeemer,’ with the prayer traditionally recited on Chanukah, which reminds those praying that the Maccabees were a tool in the hands of God,” Alon explains. “‘But You, in Your abounding mercies, stood by them in the time of their distress… You delivered the mighty into the hands of the weak, the many into the hands of the few.’ The connection to our times is clear," said Alon. "It’s not the IDF soldiers who fight to protect us, it’s God who delivers us from our enemies. This is the story and the argument even today.”

The energy that Bialik says lay dormant in Chanukah and the Books of the Maccabees, which broke out again in the Zionist movement in relation to Jewish sovereignty in the Land of Israel, can be compared to the frozen fire in the story of Nehemia’s miracle. The eternal flame morphed into frozen water and was preserved for generations. The Jews arrived and restored it to its rightful place: the conditions were right, the people believed and wanted it, and so the eternal flame sparked into life from the frozen water. What does it mean that Zionism has liberated these kinds of forces, like the fire in the ice, that were hidden from Jewish people for almost two thousand years?

Is Zionism playing with the eternal flame? For the Maccabees – who lived during the only time of Jewish sovereignty in the Land of Israel between the destruction of the First Temple and the declaration of the modern state in 1948 – it didn’t end so well. The dynasty itself lasted for 130 years, by which time the last generation was already completely subjected to foreign rule. There is much to learn about our past and the various forces which influenced the ways in which we remember it, and its many diverse lessons. The upcoming Chanukah holiday offers a renewed opportunity for study and contemplation, for shaping and correcting our ways.