For Israelis, the Sea of Galilee, or the Kinneret, personifies national mood. For most of the young nation’s existence, the Kinneret’s fresh water provided its inhabitants with the majority of its water supply. In times of drought, the low water level of the Kinneret was a physical manifestation of a state of emergency. When the rains would return, and the Kinneret’s water level would rise once again, the whole of Israel would let out a collective sigh of relief – they had survived the dry season, and their store of the most vital commodity for human survival in Israel, in Israel, on the edge of the desert, had been temporarily restored. Today, news outlets still breathlessly publish the Kinneret's water level after rains or droughts. But this kind of concern for the Kinneret’s water level just doesn’t make sense any more.

"In the State of Israel, people only talk about the health of the Kinneret in terms of its water level, and I am constantly trying to convince people otherwise. Folks, the water level only concerns us when we need it for drinking water." These are the words of Prof. Moshe Gofen, one of the world's premier experts on the Kinneret, in an interview with Davar in light of the publication of his new book, "different Kinneret". Today, with more than half of Israel’s water supply coming from seawater desalination, as part of a wider strategy to better deal with changing climate conditions, Gofen urges us to completely rethink the way we understand the Kinneret.

He urges us to focus not on the lake's ability to provide Israel with drinking water, but rather on its ecological balance, water quality, and resilience to tourism and fishing.

Gofen, the former director of the Kinneret Research Laboratory, offers his insights and recommendations from 52 years of research and work on the Kinneret. In his new book, he reviews the changes that the lake has undergone in the last 25 years. In addition to rejecting the Kinneret’s water level as the only (or even a central) measure of its health, Gofen argues that with Israel’s transition to drinking desalinated water from the Mediterranean Sea and its subsequent reduction of pumping from the Kinneret, the time has come for a new, ecologically-minded approach to maintaining the Kinneret.

"Up until the 1990s, several changes took place in the Sea of Galilee drainage basin, in accordance with guidelines, and in collaboration with us (The Kinneret Research Laboratory), in order to preserve the Kinneret. Two main things were done. Firstly, the total area of the fishing pools in the Hula Valley shrunk from 17,000 dunams to 3,000 dunams, which greatly reduced the amount of pollutants that flowed into the Kinneret from the Hula Valley [north of the Kinneret]. The other change was related to the processing of sewage. Up until the early 1980s, unprocessed sewage from the Upper Galilee, at about 29,000 cubic meters a day, would mix with water from Jordan and flow into the Kinneret," explained Gofen. "This sewage was redirected from the Kinneret, and the amount of pollutants in the lake immediately dropped."

"But it is not enough to merely reduce pollutants, you also need to know how much of each pollutant is being reduced," he said. "It turned out that we were mainly able to reduce the amount of nitrogen pollutants flowing into the Sea of Galilee, while the amount of phosphorus remained constant (because the lake's phosphorous originates from the lake bed itself as well as from dust from the Sahara) So what happened in the Sea of Galilee? The amount of nitrogen in the water dropped when we reduced pollutants, and the amount of phosphorus did not change. Once you change the ratio of nitrogen to phosphorus, you also dictate which kind of algae grows in the water."

Gofen, who began his work at the Kinneret Research Center by studying aquatic zooplankton, is accustomed to looking at the lake through a microscope. This experience probably helped him understand how this change in algae composition could adversely affect the water quality of the entire Sea of Galilee. "Until the early 1990s, there was a kind of algae in the water known as peridium, and we knew how to manage it. Mekorot [Israel’s national water company] also knew how to deal with these algae very effectively," he explained. "Peridium algae had certain characteristics which made the process of removing them from the drinking water supply relatively painless. First of all, they were large and heavy, and additionally, as soon as you put chlorine in the water, they stopped floating and sank to the bottom where they were easy to remove."

-

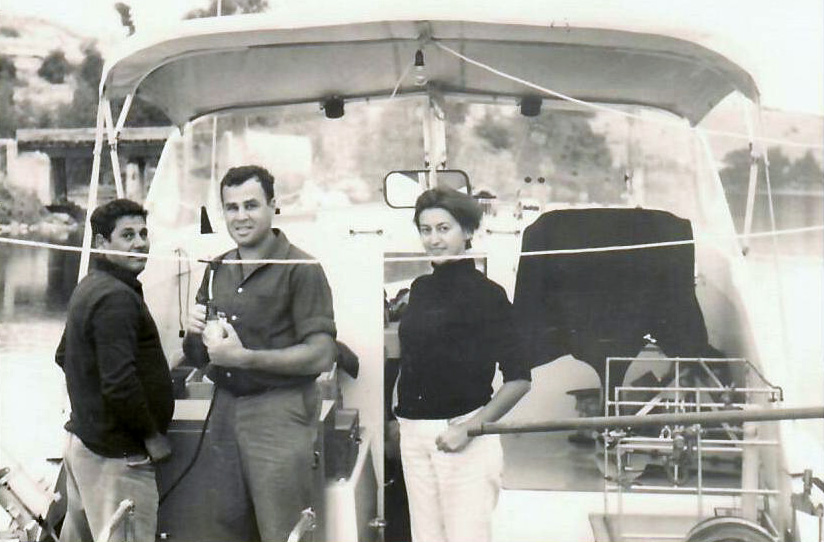

Moshe Gofen in his early days at the Kinneret Research Laboratory, studying zooplankton through a microscope, May 1968 (Photograph courtesy of the interviewee)

Moshe Gofen in his early days at the Kinneret Research Laboratory, studying zooplankton through a microscope, May 1968 (Photograph courtesy of the interviewee)

"After the nitrogen-to-phosphorus ratio changed, new algae started to appear that did not respond to these methods," he added. "These are not algae at all, but rather actually bacteria called cyanobacteria (blue bacteria) and they thrive in nitrogen-deficient water, because they can bind free nitrogen from the atmosphere. They first showed up in the Kinneret in 1994."

"Seven years before cyanobacteria was first detected, I warned that if the nitrogen downturn and phosphorus stability continued, they would show up. I talked about it everywhere and everyone laughed at me," says Gofen. "While I was a visiting professor in the U.S., I called the Kinneret Research Laboratory one day, and one of the employees told me, ‘Between you and me, your blue bacteria has appeared.' It took seven years. The cyanobacteria were probably waiting for me to go overseas."

However, Gofen emphasizes that the situation is not irreparable. "Occasionally, when there is a flood and a large amount of nitrogen reaches the Kinneret, the native peridium algae return. They can reappear when they have appropriate nutrients [more nitrogen]. It is not impossible that this year, if such floods continue, there will be a bloom of the algae. Last year there was a small peridium bloom," he said.

Doing shots to save the St. Peter’s fish

Gofen's desire to preserve the Kinneret and its water quality often led him to mediate between the various groups that depended on the lake for their livelihood. For example, he described the conflict with the local fishermen over a proposed tilapia (St. Peter’s fish) fishing ban during mating season. "The tilapia often reproduce in a valley located in the slopes of the Golan Heights and the eastern Galilee, northeast of the Sea of Galilee, where they are relatively safe from predators," Gofen said. "So we said, let's look for a way to encourage tilapia reproduction. We realized this would only be possible if we forbid fishermen from entering the area where they built their nests during the period when reproduction takes place. The fishermen knew exactly when and where this took place, because they would come there to find fish."

"We came and told them 'Look, we're with you, we want a lot of tilapia here, both for fishing and for water quality, and that means you can’t fish during the breeding season' (two months a year)," he continued. "It started a world war. We were told, 'You are robbing us of our livelihood,' 'You are abusing us,' 'We live off our daily earnings,’ and other such things."

"I went to their homes and met with them. And it cost me a lot in arak [local liquor], which I don't like, but I was able to eventually win them over," describes Gofen proudly. "Then, when we brought the proposal to ban fishing in the area during the breeding season to the water authorities, the water authorities told us: 'Listen, if you convince the department of fishing that this is what needs to happen, and you both agree on it, then we will.' We were unable to convince the fishing department, and then in one of the fateful meetings on the subject, I presented the position of the institute, and the fishing department presented their position advocating commercial fishing. Then the two heads of the Tiberias Fishermen's Organization stood up and announced to everyone present, 'Gofen is right,' and that was that. The decision went with us, because we were a majority, and a regulation was issued. It took us about five years to achieve."

Desalinated drinking water ushers in a different Kinneret

For almost 60 years, since the national carrier pipe was inaugurated, the Kinneret has served as Israel's main source of water. During this period, 13 billion cubic meters of water were pumped from it, a quantity sufficient to fill the lake four times. According to Gofen, this required a policy that favored maintaining a certain level of water over a competing policy that would have maintained water quality at an even lower level. “When every day a million cubic meters of water had to be distributed to the people of Israel, low water levels in the Kinneret were a cause for concern. But today you have to look at the water quality as well. And there’s a very simple fact," he explained. “If there is heavy rain, and a heavy inflow from surrounding streams which brings in a lot of water, then a lot of pollutants are flushed into the lake with it as well. What does a low water level actually mean? That means there was no rain and no heavy inflow from streams bringing in pollutants, so basically the water quality is better."

In general, Gofen sees anxiety at the Kinneret’s water level as ignorant of its history. "Out of the 20,000 years of the Kinneret’s existence, for the last 9,000 years the water level has fluctuated by 20 meters. Today we are seeing maximum fluctuations of about six meters, and what do you know, the Kinneret has not yet disappeared."

Gofen calls for seemingly counter-intuitive steps to be taken in providing a better future for the Kinneret. After cutting off the inflow of nitrogen-rich sewage from the Kinneret in the ‘80s, he now wants to bring the nitrogen back, but from a different source. "First of all, the nitrogen supply to the Sea of Galilee must somehow be strengthened. It sounds awfully strange, people say to me, 'What, are you proposing to bring back the dumping of sewage into the Kinneret?' Obviously not. But it is possible to take nitrogen from the Hula Valley [which flows into the Kinneret from the north] and direct it to the Kinneret."

"Secondly, we need to control and reduce the phosphorus coming in from the drainage basin," said Gofen. The phosphorus coming in from the lake floor or from atmospheric dust is impossible to control, but what flows in through the drainage basin is possible, as it has to do with cowsheds, cattle and sewage. We need to carry out an extremely intensive water rotation, even if it means a temporarily low water level – what’s known professionally as ‘shortening the water’s stay in the lake’, i.e. to bring in clean water and get rid of the dirty water. Or the government could bring desalinated seawater to the Sea of Galilee."

Another surprising suggestion has to do with sardines. According to Gofen what we need is a comeback of sardine fishing in the Kinneret. "It's really a one-of-a-kind story. There are little green algae in the Kinneret, who get eaten by microscopic crabs. But the crabs, are getting eaten too, by the sardines. Once upon a time, 1,000 metric tons of sardines were fished from the Kinneret every year – today it’s hardly 200, because nobody’s buying them. Now there are a lot of sardines and their numbers need to be reduced. If there were fewer sardines, there would be more crabs, and the crabs would eat more seaweed – which is ultimately good for water quality."

In describing his vision for the future of the Israel’s only lake, Gofen said that "I imagine the Sea of Galilee 25 years from now as I saw it 25 years ago. An ecosystem that serves all its users. For water supply if needed, for fishing, recreation and swimming. And I see it returning to the quality of water it had 25 years ago." He also mentions the importance of nurturing the Kinneret’s delicate chemical balance and microbiome – a task for his beloved microscopes, test tubes and water scales – all in the name of "maintaining a controlled and healthy pollutant ratio that will maximize water quality."