In 1930, the world-famous British economist, John Maynard Keynes, predicted that technological advances would allow his grandchildren's generation to make do with only 15 hours of work per week. According to his prediction, his grandchildren would be able to retire much earlier than him, spending vast amounts of free time pursuing their true interests: family, art, music, and so on. Unfortunately, Keynes' prediction failed to come true, and in Israel not only is the retirement age rising, but pensioners might soon see the government slashing their pension payments.

Israel has some of the highest rates of poverty among old age pensioners, and government-owned pension funds might soon see a 1.2 percent cut. Even though the government has agreed to postpone the cut until April 2020, following a protest backed by the Histadrut, pensioners are preparing to return to the streets in two months if the government does not find a way to prevent the cuts.

Old age poverty in a rich country

"I worked all my life, and I receive NIS 1,530 from state pension, and another NIS 1,300 from my pension fund" said Samira Seniun in a Knesset committee hearing held last year, that was devoted to worrying levels of poverty among old age pensioners. "I rent a room. I have to pay rent, together with all expenses, bills and everything. I also have to spend NIS 1,000 a month on medical treatments. I have to rely on charities to survive. If pensions were high enough to offer a decent standard of living, I wouldn't be in this state today."

Seniun's plight is certainly a one off. In fact, Israel has some of the highest rates of poverty among old age pensioners. According to OECD data, 21 percent of Israeli pensioners live below the poverty line, in unsustainable financial conditions. This is compared to only a 12 percent average among OECD member states. The picture gets even worse among older pensioners: one in every four pensioners over the age of 76 lives in poverty in Israel.

For older people, poverty is no less than a matter of life and death. Often, older people with low incomes are forced to ration even their most basic needs, having to decide whether to spend money on heating, food or medical treatments. It has become an all-too-common occurrence for Israelis to discover their elderly neighbors dead in their apartments. This year's harsh winter has not made matters easier.

Not only is this putting a great strain on retirees, it also forces many Israelis to continue working after the age of retirement. In recent years, more and more pensioners have returned to the labor market after retirement, and it has been one of the reasons that many Israelis choose to keep working after the age of 65. In fact, 22 percent of Israelis over the age of 65 continue working, and a staggering 12 percent of Israelis over 70 are forced to continue working, often in low-wage jobs, in order to sustain themselves and compensate for low levels of pension payments.

"I would like to enjoy my pension years but I simply can't. I'd rather continue working than starve to death, wouldn't you?" says Haim Atias, a 71-year-old who, after retiring for a year, returned to work as a security guard at a shopping center in Tel Aviv. "I just realized that I'm better off working as long as I can. I'd rather work than be poor."

A survey conducted last year by Hasdei Neomi, one of Israel's largest charities, found that pensioners in Israel are often pressed to cut back on essentials for financial reasons. The survey found that just last year a quarter of pensioners were forced to skip medical treatments to save on expenses, while 27 percent chose to skip meals, and 35 percent avoided using any form of heating during winter.

Low state pensions

So how does poverty of this kind exist within a relatively rich and developed economy? Of course, as experience shows, the overall riches of a given society tell us nothing about the ways in which those riches are divided up among its members. But in Israel, pensioners’ poverty has for years been a major predicament, with only slight progress made in recent years.

As in all developed countries, Israel's pension system is divided between the state and private systems. While every employee sets aside a portion of their income towards a pension fund and accumulates capital that is paid back to them after retiring, the state also funds a portion of those payments out of its welfare budget. These payments, paid for by the state, are known as state pensions. According to pension activists, one of the main reasons for the high levels of pensioner poverty is low state pensions.

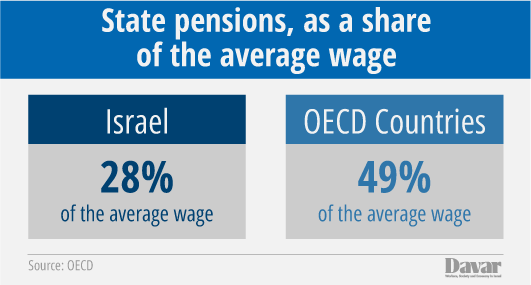

In fact, state pensions in Israel are among the lowest in the developed world. While the OECD average for state pensions is 49 percent of the average wage in the labor market, Israeli state pension payments amount to only 28 percent. In other words, Israeli state pensions are just over half the average among developed countries. Israel is also one of the lowest spenders among OECD members when it comes to pensions. While the average stands at 8 percent of GDP spent by governments on state pensions, the Israeli government spends only 4.8 percent of yearly GDP on pensioners.

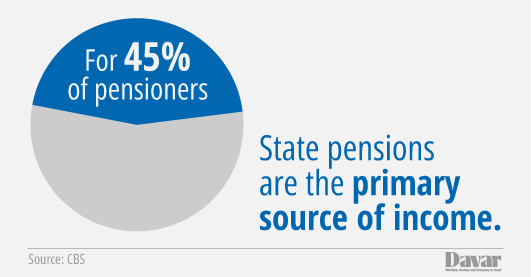

State pensions in Israel amount to a monthly payment of NIS 1,554 ($450). Israel officially regards an income of NIS 5,216 ($1500) to be the poverty line for households of two. In other words, state pensions alone do not offer enough income to ensure a decent standard of living, even though according to government statistics, 45 percent of Israel's pensioners rely solely on the state for income after retirement, and have no private pension fund.

Pensions are usually measured by a term known as 'replacement rates', which calculate the level of income after retirement as a share of income received while working. In this respect, state pensions fail miserably- they amount to an average of only 18 percent of income gained before retirement. This means that for many older Israelis, retirement can mean a huge reduction in income, and often outright poverty.

Why do so few Israeli pensioners have a retirement plan?

In the past, a large part of the Israeli economy was owned by the country's largest trade union, the Histadrut. Workers who were employed by these semi-cooperative companies were automatically enrolled in a collectively-owned pension scheme. In fact, the Histadrut managed several large pension funds, which provided for members' retirement years. These collectively-owned pension funds covered a large portion of Israeli workforce up until the late ‘80s.

The problem was what happened to the rest of the workforce, who were not members of trade unions. Private pensions were historically quite rare in Israel, and usually owned only by the very rich. In fact, up until 2008, pension contributions were entirely voluntary, meaning that employers could opt out of including pension contributions in contracts. Workers who were backed by trade unions usually managed to secure pensions as part of collective bargaining. Most workers who were not trade union members, however, unless they happened to work for a particularly benevolent employer, did not.

Although the question of mandatory pension contributions has been discussed since the early ‘50s, it was left as an open question for many decades – which left many working Israelis with no retirement plan whatsoever. This only changed as late as 2008, when the Histadrut managed to push for the enactment of legislation that made pension contributions mandatory for both employers and employees. This has significantly raised the number of Israelis with retirement plans, but has not been enough to solve the problem of low-income pensioners today, who have spent their lives working without accruing any pension contributions.

State pensions, first enacted in 1954, were meant to be the backstop against old age poverty. From the outset, state pensions were set a quite a low rate – only 25 percent of the average wage at the time. Problems arose surrounding the way these pensions were updated to prevent devaluation. State pensions were linked to the Consumer Price index, and would automatically rise together with the prices of certain basic products. However, in the ‘60s, average wages rose considerably faster than the Consumer Price index, which led to a dramatic erosion in the value of state pensions. By 1965, pensions were worth only 10 percent of the average wage.

These pensions were occasionally raised, usually by centralized negotiations between the government and trade unions, but state pensions remained too low to secure a decent retirement for workers without private retirement plans. Even with additional benefits added to compensate, state pensions in Israel have always been low in comparison to other western countries.

Cutting pensions and raising the retirement age

But the current protests are not concerned with those pensioners without retirement plans, but with those who do have a pension fund. The main point of contention is a government decision to cut private pensions by 1.2 percent.

The government is free to do this because, in fact, these funds are run not by private companies but by the government itself. Since the establishment of the State of Israel, the largest pension funds were owned and run by the trade unions, until in 2003, when Minister of Finance at the time Benjamin Netanyahu ordered them to be nationalized. The reason Netanyahu gave for this was what is known in the pension industry as an actuarial deficit. This means that at some point in the future, the fund's commitments are expected to overtake its income, making it unable to pay out all of the pension payments owed.

Netanyahu's decision was to nationalize the funds, with the government funding any future deficits. As a result, the government paid NIS 78 billion into the funds, but this decision came with a price, mostly paid by pensioners themselves. In an attempt to reduce the fund's commitments and improve its balance sheets, the Netanyahu slashed 20-25 percent off pension payments, and formulated a plan to gradually raise the official retirement age from 65 to 67 for both men and women.

This is the crucial point, and in many respects the cause of the current crisis. The retirement age has been raised from 65 to 67 for men, and from 60 to 62 for women. In recent years, the government has been trying to raise the retirement age for women to 64, with little success. While some MKs have demanded a solution for low-income women who are employed in difficult or manual-labor jobs, the Ministry of Finance has refused to allow the government to cover the costs. Dorit Salinger, who is in charge of managing the funds for the government, declared in 2018 that unless an agreement was reached and the deficit funded, pensions would have to be cut by 1.2 percent by July 2019, affecting over a quarter of a million pensioners.

After the trade unions intervened over the summer, threatening to strike if the issue was not resolved, the Ministry of Finance agreed to fund the deficit until next April. This would give the government time to produce legislation which would raise the retirement age for women without hurting low income women near the age of retirement. But with only two months to go, during which a third consecutive election will be held, pensioners may soon find themselves returning to the streets in an effort to prevent the cuts.

If and when they do, they will not be there alone. Arnom Bar-David, Histadrut chairman, said in a union pensioners' conference this January, that "The most crucial thing this year is raising state pensions. I am fully committed to this, even if it means higher social security contributions from workers. In the coming years, pensioners’ welfare will become one of the most urgent political topics in Israel. We will do everything we can to deal with the problem of low state pensions. I've designated 2020 as the year of the pensioner, and I call on both the government and employers to come to the table and negotiate a tripartite agreement to raise pensions and pensioners’ welfare."