The Israeli Health Ministry has signaled that it intends to outsource all coronavirus testing to private companies and research centers in an effort to increase the rate at which it can screen for cases of COVID-19. For a nation which prides itself on the sturdy backbone of its public health services, the move to privatize coronavirus tests in Israel may come as a surprise. Currently, COVID-19 screenings are being carried out by 20 public laboratories. The new plan will be expensive and time-consuming to execute, requiring installation of new facilities and hiring and training new staff who would not be certified under Israeli national health law to facilitate laboratory tests of this kind.

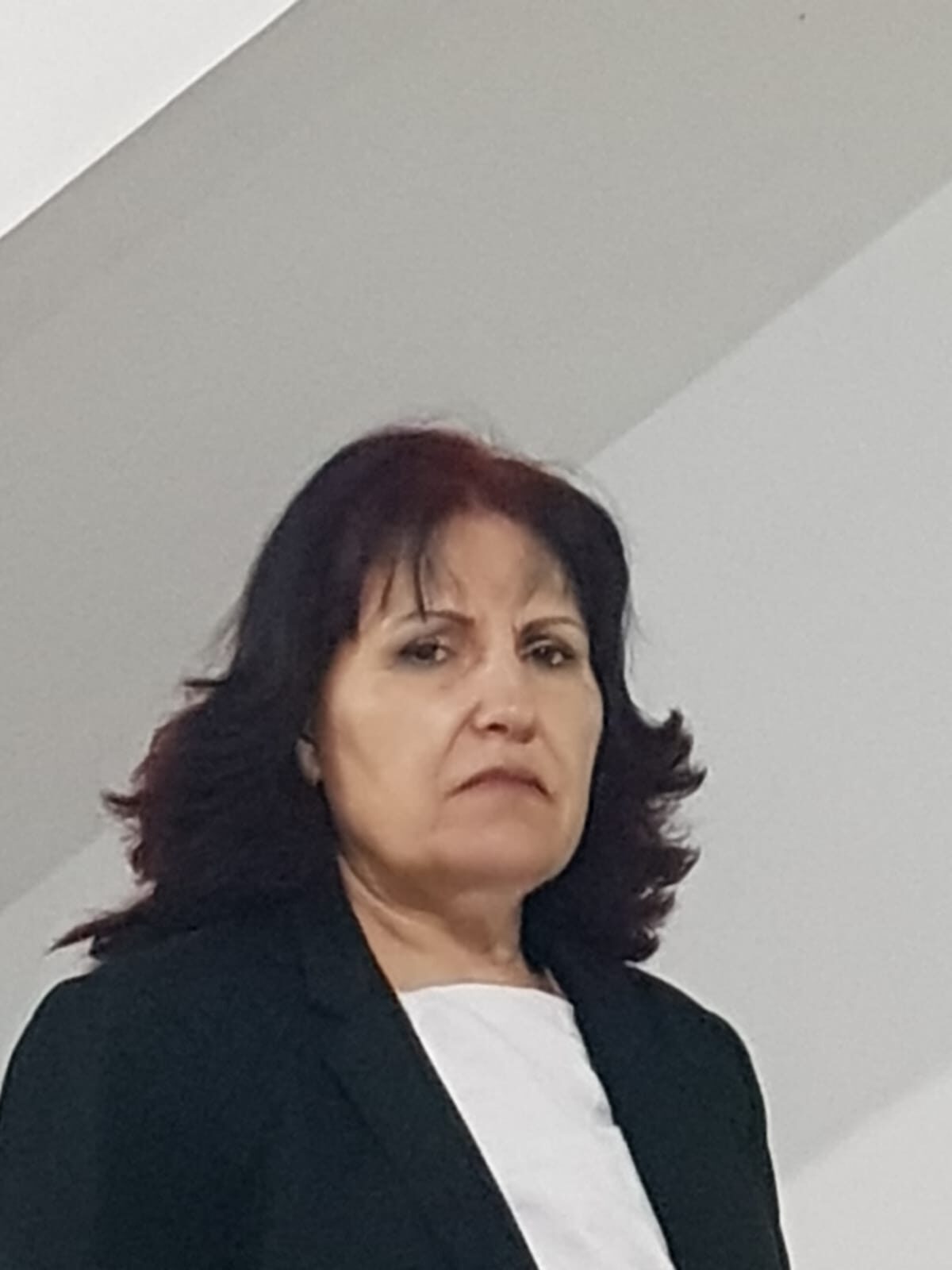

Esther Admon, chair of the Israel Association of Biochemists, Microbiologists and Laboratory Workers, wrote a letter of outrage to Health Ministry chair Moshe Bar Siman Tov on Wednesday, decrying the move on behalf of public laboratory workers. “We (the public laboratory system) could perform over 3,000 reliable tests per day if you would only utilize the existing public workforce, by updating compensation [whose negotiations] still remain frozen,” she wrote. The union claims that as a result of years of stalled negotiations over intolerable compensation and conditions, the readiness of the state of Israel in responding to health crises such as Coronavirus has deteriorated to a dire level.

There was a salmonella outbreak, and after that there was a polio outbreak. We shouted again and again, ‘get your act together!’ And now there’s Corona – the writing was already on the wall

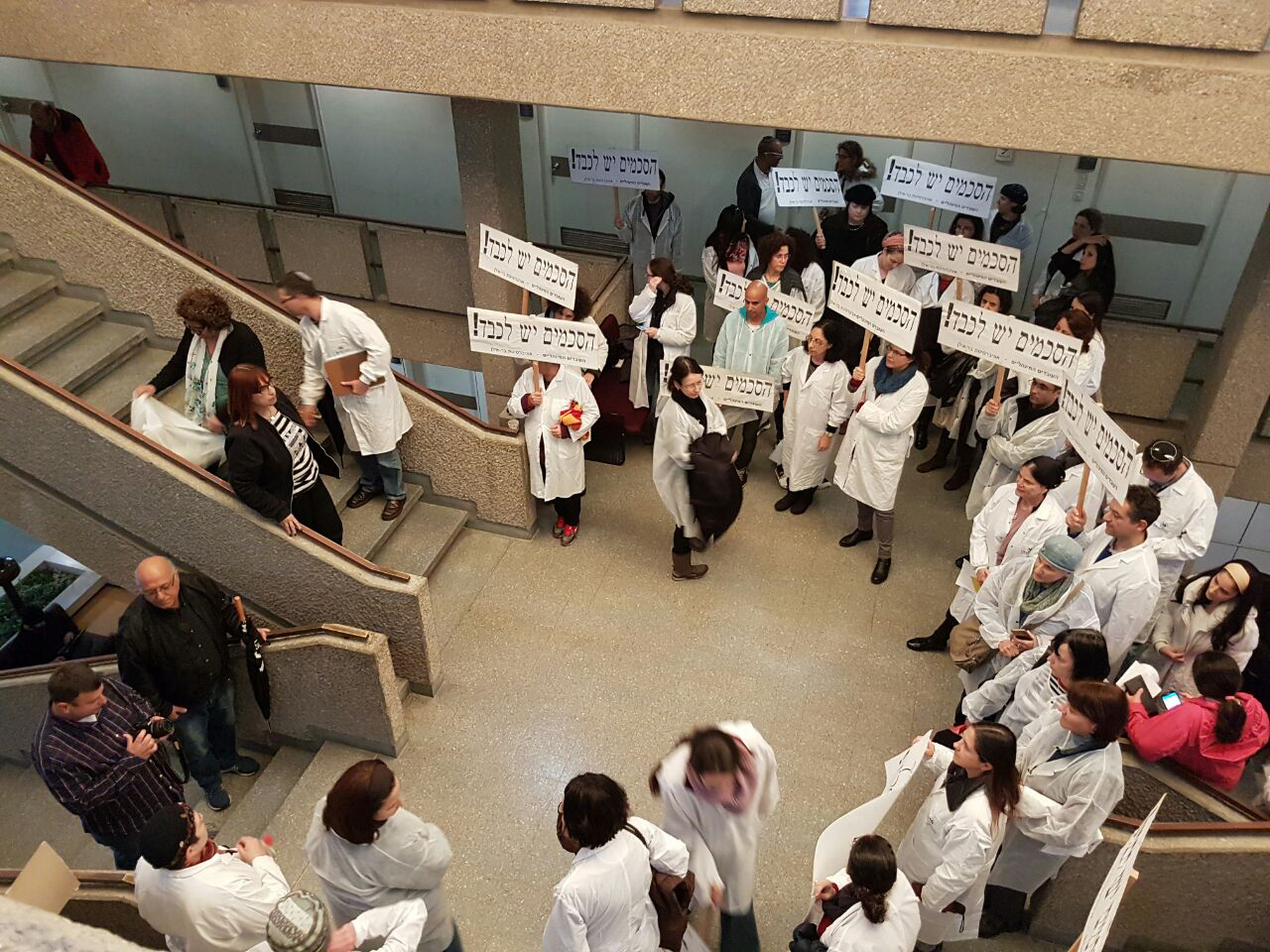

The notion that all is not well for Israel’s laboratory workers, however, is not new to the Health Ministry. The struggle for improved compensation and working conditions in medical labs across Israel has been an ongoing battle for years. Indeed, almost a year ago, tensions flared when on August 1, 2019, Israeli public laboratory workers staged a protest that was unprecedented both in severity and in scale. Three thousand medical laboratory workers across the country declared a strike, refusing to perform any tests on blood, urine, stool, and throat swabs from the morning until the afternoon. The only tests performed that day were those classified as emergencies, for patients in intensive care or in other high-risk conditions. The medical lab workers, having been stonewalled in government negotiations for years, cited as the reason for their strike a slew of problems: abysmally low pay, impossibly long shifts, severe staff shortages and deficient workplace standards.

Katia Levitsky, a graduate of Hebrew University Medical School, described this reality from first-hand experience: “When I started, after graduating with a master’s degree, I was earning 27 shekels an hour, the absolute minimum – I would have earned more working in a store,” she said. Levitsky started working in a medical laboratory at the blood bank at Wolfson Hospital in Holon in 2015. “I went to work in the laboratory because I loved it. I also love research, and I did research for many years, but then I decided that I wanted to offer my services in a clinic, to encounter real situations and not just experiments in a lab. So, I went to work in the medical laboratory. But after I understood what my pay and working conditions were like – I regretted the move.”

"Every year the workload just increases. There are always more tests, more diseases, and new mutations, but compensation doesn’t increase and there aren’t enough workers," she said. "Sometimes you work 23-hour night shifts in the blood bank, only because 24 would be illegal, and then the next day you have another shift because there just aren’t enough workers.”

Three years prior to the strike, in 2016, a state comptroller report was published which severely criticized the conditions that laboratory workers were being subject to, citing “a projection of significant shortage in qualified manpower in the very near future that is complicated by the low salaries and lack of prestige for this profession.” According to the report, over 50 percent of lab personnel were over the age of 55 and intending to retire in the next 2-3 years, with no junior technician likely to replace them. The report views the Health Ministry as accountable for this public health crisis: "Assuming that the Ministry of Health recognizes the vitality of the clinical laboratories in [the] overall medical system, some priority should be given to improving the basic conditions of lab workers in order to raise the incentive to join this profession.”

In hospitals we have the infrastructure ready to carry out more tests immediately, but this has not been ordered

This charge, nevertheless, remains unanswered: “Since 2016, there has been total refusal to acknowledge the state comptroller’s report,” said Admon, chair of the union. “We had discussions in the Knesset and forced them to meet with us. They promised to sit down with us and move things forward. We met with the Treasury and gave them ideas – but everyone dragged their feet.”

Four years later, Admon is adamant that public labs, despite being sidelined by the Health Ministry in the unfolding developments surrounding coronavirus testing, are more than capable of meeting the increasing demand for testing for the disease, should the Health Ministry actually invest in bringing them online at full capacity. “In hospitals we have the infrastructure ready to carry out more tests immediately, but this has not been ordered. The existing clinics are operational from 8:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. We need to expand them to operate 24 hours a day, and run them in shifts. And then, believe me, we can perform up to 10,000 tests a day. However, the Health Ministry is adding insult to injury, by transferring the entire operation [to private companies].”

She explained to Davar that the current plan to outsource testing to private companies is irresponsible: “We’re talking about sensitive tests that need to be carried out in accordance with the national health laws, by people who have been certified and trained in the field – it takes medical expertise. There’s no way they have had the basic training required to facilitate these tests,” she said. “Tests carried out by unregistered parties are likely to be dangerous. A patient who is infected with the disease is liable to come out ‘negative,’ for example, when there are no proper control systems in place.”

Amid all the panic, it is unclear why the Health Ministry refuses to use existing infrastructure, opting instead to set up new operations at the Weitzman Institute (as was announced in the media), whose physical construction, as well as the acquisition and training of new workers are expected to take a long and critical period of time,” wrote Admon to Siman Tov.

It could have been prevented

Perhaps if the Health Ministry had heeded the warnings that something needed to change back in 2016 after the state comptroller’s initial report, or even last year after the laboratory workers’ strike, then the current coronavirus testing crisis would never even have surfaced. If the Health Ministry had implemented comprehensive reforms across public laboratories as soon as the problem had been identified, or indeed in any of the years since, then there would have been no need for the expensive last-minute construction of emergency privatized labs at this moment, amid the largest outbreak of a global pandemic in living memory. In the meantime, while plans are still being drawn up, COVID-19 cases continue to soar in Israel, with thousands going untested each day.

Admon accurately captures the sentiment: “There was a salmonella outbreak, and after that there was a polio outbreak. We shouted again and again, ‘get your act together!’ And now there’s corona – the writing was already on the wall. But even now, instead of pouring money in the public health system, they are paying out foreign ghosts, research centers – letting people who have never in their life conducted tests run the operation instead of us.”