The volunteers go to the hospital early in the morning and leave only when the last child is taken home by their parents. Because all educational institutions in Israel have been closed down, the counselors at the daycare centers for children of hospital workers are the only educators in Israel meeting children in person. Today, they tell Davar how they keep educating in an almost impossible environment.

No parents allowed

The doctors, nurses, administrators and lab workers staff the Poriya Medical Center for intense 12 hour shifts. Working in hospitals is stressful any time of year, but the coronavirus is doubly stressful for the workers.

They all come from different places, there are Jews and Arabs, kibbutznikim, moshavnikim, and city people. The only real thing they have in common is that their parents work at the hospital.

In order to enable the staff to go to work, the hospital management decided to establish child care at the hospital. “It’s a real day camp, trying to create routine during these uncertain and abnormal times,” says Yan Tayar, the daycare center director for the Jordan Valley Regional Council, which has taken this job on in partnership with Dror Israel. “Unlike a regular day camp, the children are not allowed to meet outside these groups with any other kids or counselors, so everyone is stuck with one another until this coronavirus period ends.”

Each morning, the counselors and kids come to the hospital, take the childrens’ temperatures, and divide up into small groups of eight children ages four to ten, led by counselors from Dror Israel and soldiers during the “national volunteering” period at the end of their service. “They all come from different places, there are Jews and Arabs, kibbutznikim, moshavnikim, and city people. The only real thing they have in common is that their parents work at the hospital,” explains Tayar.

“It’s no simple challenge, running childcare with so many limitations,” says Alon Oppenheimer, the educational coordinator for children ages seven to nine. “Each morning, we check how many kids arrived, everything is so strict, they can enter the hospital only after checking temperatures. The parents themselves are not allowed to enter the activity area.”

Oppenheimer and his staff, who have extensive experience in informal education, have been working in recent weeks to develop a completely new curriculum for this new situation. “We are trying to run all the kinds of activities of a regular youth movement day camp. The counselors came here to be educational figures for the children,” he tells us.

As an example, Oppenheimer describes how the educational staff at Poriya decided not to give up on a storyline told day by day through skits with the counselors as the actors – a staple at any Israeli youth movement camp. Because the children are not allowed to all be in the same place at the same time to see the skits, the counselors recorded skits on video ahead of time, and each small group watches the skits together each morning on video.

“We recreated the entire idea of the day camp storyline. It’s an important element in creating the educational experience and enjoyment of the activities. We asked our friends, who are also educators, to record video skits, and each day we play one video in the series of the story which guides us each day. The story allows us to leave our routine life behind and create a different world from everything happening outside.”

A human touch

Anyone who has ever been with small children is sure to wonder how activities can be run for them without touching. To this question, the counselors have some complex and original answers.

“Preschool-aged children need touch – as much as we could try not to, there’s no way around it,” says Shai Avidan from Ramat Gan, who is volunteering at the child care center in Sheba Medical Center. “We’re trying to create a bridge or compromise between the need to maintain physical distance and the children’s educational need – there’s the matter of setting boundaries, but also the children’s basic needs.”

Since school was cancelled about a week ago, Avidan, who should complete 12th grade this year, rides his bike each morning to Sheba Medical Center to volunteer with the children. He started volunteering after contacting the Lev Ehad organization, which is organizing volunteer counselors for child care at hospitals throughout the country. “I couldn’t just sit at home, seeing the situation of the healthcare system and the incredible pressure on medical staff,” he said.

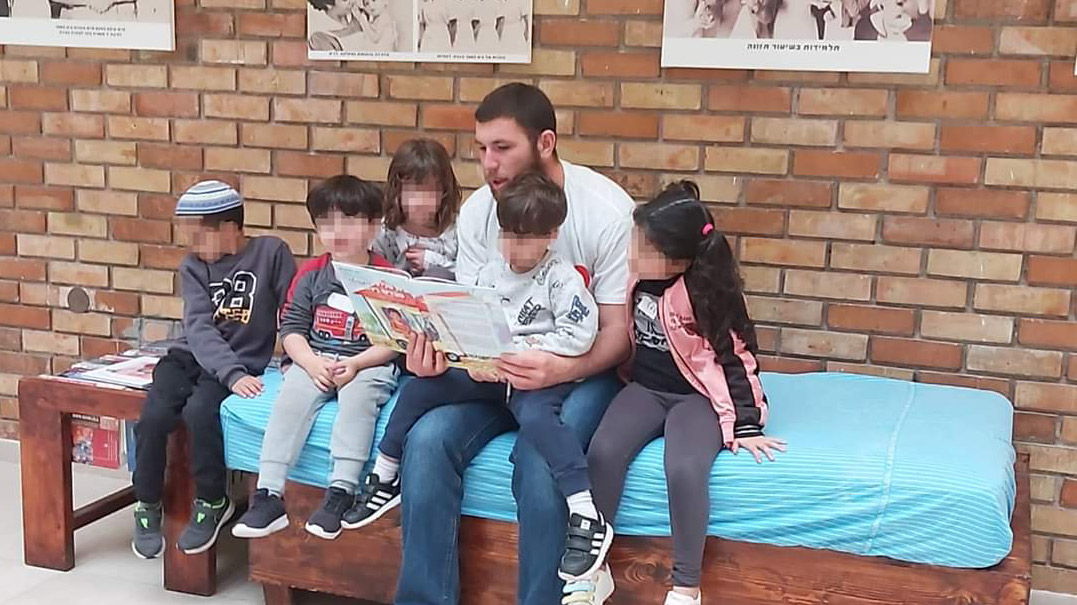

Avidan tells us that while the older kids understand the severity of the situation and know to maintain distance from one another, for preschool-aged children, it’s very hard to keep that kind of discipline. When Avidan reads them a story, all of the kids want to sit on his knees. “I needed to improvise to a certain extent, and also bend the guidelines,” says Avidan, laughing. “We try to keep the groups as small as possible, and of course keep everything clean all the time, but it’s hard. We’re constantly getting updates about new regulations, constantly disinfecting our hands, every hour.”

At Poriya as well, Oppenheimer notes that it’s hard to keep everyone at a constant distance of two meters from another, and therefore the counselors are also protected with gloves and masks. “The separation between the groups is absolute,” he says. “We do everything possible to prevent a situation in which if someone from one group is infected, another group is infected too… It’s not convenient, it’s a bit strange – but we have no choice.”

Children understand everything

At the child care center at the Abarbanel Hospital in Bat Yam, the children spend their time listening to stories and coloring. “The weather just improved, so now we can go out into the yard, too,” says Sharon Marlene, a teacher in the Karev program from Mazkeret Batya, who has decided to dedicate her unpaid leave to volunteering here.

“Here, the children bring food from home. The smallest girl is three and a half years old, so we have to be creative in building the program,” Marlene explains. “They all understand really well the situation that has caused them to go with their parents to work every morning. They know that their parents are doing important things.”

“Children ask a lot of questions, and we try to show them that we are here for them,” says Avidan. “The children are smart and understand what’s going on. Yesterday, a four-year-old boy came up to me and explained to me the difference between a virus and bacteria.” He said that these are the moments in which “you just understand the greatness of what’s going on around us. Sometimes it really shocks me.”

Giving the parents some sanity

One of the main reasons why the education system was shut down is so people can maintain distance from one another, but the counselors, who are fully aware of the danger to themselves and their households, claim that their commitment to the work is stronger. “When I come home, first of all I change my clothes and shower, in order to take care of myself and those I live with,” explains Marlene, who started volunteering following her daughter’s lead, who was also looking for a place to volunteer. “We were very careful to stay at home for the past few days, and took good care of ourselves. But everyone at home accepts and supports this work.”

“The parents’ responses are really moving. They tell us that the children come home and can’t stop talking about their experiences, and just want to go back,” says Oppenheimer. “I think that this is because of the commitment, investment and dedication of the children’s counselors, and it’s worth it.” Hoppenheimer is a member of a Dror Israel educators’ community in the north, and he says that his partners are aware of the danger, but support his work. “There was an understanding among us that we’re going to do this together – meaning that if I am going to coordinate the child care, then it could endanger all of us. I’m doing it together with two other friends of mine.”

“My parents totally support what I’m doing, and they understand that there is a certain amount of danger involved,” says Avidan, who is planning on volunteering until the end of the crisis. “The most significant thing for me is that we’re giving the parents some sanity, some calm, something to lean on. As a person who is part of society in Israel, I could of course sit at home and not go out as the government demands – but just like the army can’t fight without combat support, I’m serving here as combat support.”