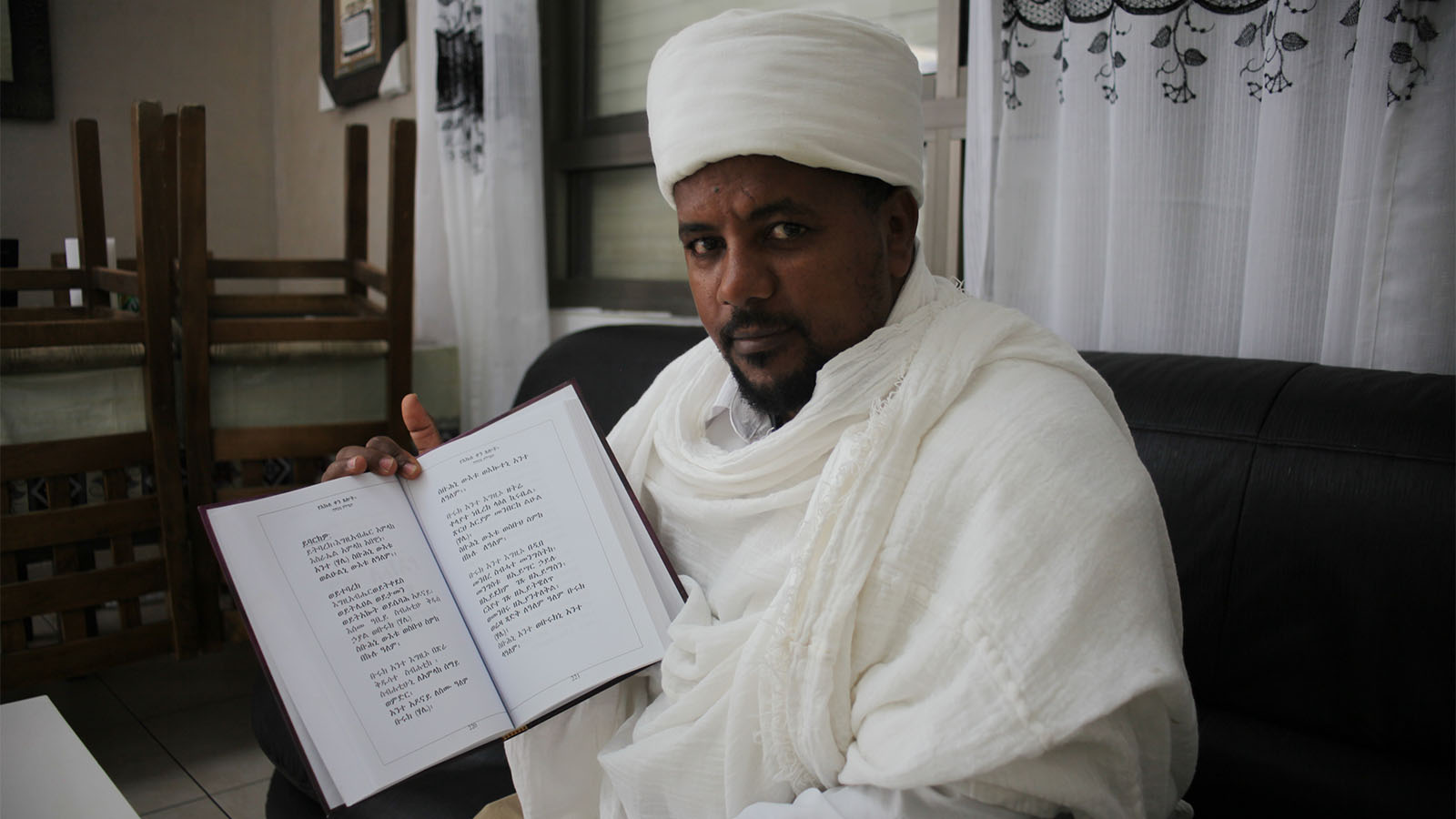

Yerge Ayasa was 5 years old when he, along with his family, left their village and embarked on a perilous six-year journey, eventually arriving in Israel. “We dreamed of this and thought that all of Israel was Yerusalem. That the whole country was holy like Jerusalem,” says Ayasa, 39, in the living-room of his house in Ramleh. Behind him rests a bookshelf filled with Jewish holy writings.

Remembrance Day for those Ethiopian Jews who perished on their journey to Israel is tied to Yom Yerushalayim, which was marked last Friday, May 22. This year the traditional march to the capital did not occur, nor will local commemorations. “We will pray in our homes, outside, and at synagogue, in accordance with the regulations. We are doing what we can.”

A place filled with beauty, peace and serenity

30 years before the coronavirus prevented him from marching to Jerusalem, Ayasa listened to the Friday prayers on his small radio which members of his family smuggled, with help of the Red Cross, into the detention camp where he was held in Sudan. He was 9 years old when he heard the Kesim (Ethiopian Jewish spiritual leaders) in Jerusalem praying for the peace and well-being of Prisoners of Zion (a Jew imprisoned or deported for Zionist activities).

“The head Kes prayed for us, do you understand that? That is a massive inspiration which gave us great hope. Many people did not know what they wanted to be when they grew up, but I, at age 10, already knew that I was going to be a Kes. I remember that I told myself: In the future, I want to give hope to other people – like that which was given to me.”

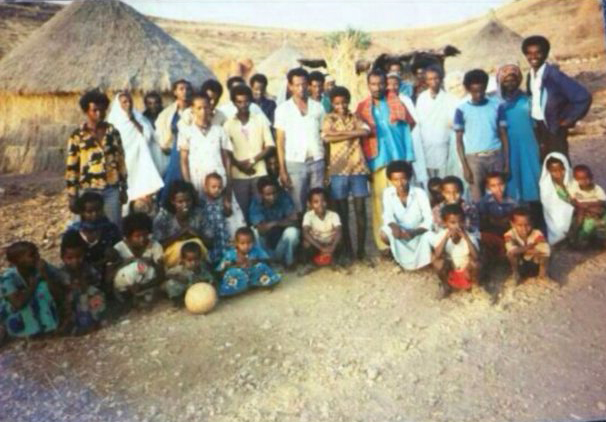

A few years prior to that same Friday evening, Ayasa’s family, which lived in Sayaman, a small village in the Gondar District in northern Ethiopia, decided it was time to leave for Yerusalem. The rumors about the possibility to do so had reached the village by around 1984, a short time before the beginning of Operation Moses [between November 21, 1984 and January 5, 1985 Ethiopian Jews who managed to make their way to refugee camps in Sudan were flown to Israel]. “My father and a few other men got together and decided to embark on a journey towards Sudan. We set out, 54 people, among whom were eight members of my family: five siblings, my father, mother and grandmother.”

How did you imagine Yerusalem?

“From an early age you are told that Yerusalem [Jerusalem] is a land made of gold and precious stones. As is written in the Torah about the period of Solomon. That the temple is there. A place full of beauty, peace and serenity. That was an inconceivable dream, that spoke to me even as a small child. That is the dream which gave me the strength I didn’t even know I had. Many times you hear of people who “ran away,” but with us that simply was not the case. My father was a very rich man with land and many assets. He chose to embark on the journey because he wished to fulfill his dream of living in his own land.”

Six balls of dough a day per person

The preparations for the journey on foot from Ethiopia to a transit camp in Sudan went on for a long time, and included the gathering of supplies for the journey that would allow for continuous walking. “We prepared balls of dough which were called “tzanek.” It’s basically flour that you mix with a little water and roll into small balls which you can eat after putting them into the fire. You could gather a very large amount of those in a large bag. At every food break we ate two of those, and all up we ate six or seven of these each day and that kept us going for many days.”

“I remember the excitement and the conversations we all had about the fact that we were going to Yerusalem. When I tell people that all this happened when I was 5 years old, they compare that to the mentality of a 5-year-old today in Israel. They do not understand that it’s another world entirely. In my village, children of six or seven years would already be sent out to the fields to watch over the sheep. That’s a huge responsibility. Today I have a daughter that age and I’m scared to let her go to school by herself,” he laughs. “But I, at age 5, was already expected to complete this journey on foot. Only my little 3-year-old brother went with grandma on the donkey. It took us two weeks to leave Ethiopia by foot. We walked only at night so that the Ethiopian authorities would not catch us. Only once I had arrived in Israel did I comprehend the insane distance I had walked – 750 kilometers.”

The turning point

The long journey to Sudan, taken by 54 members of the same village, including Ayasa’s family, was led by a guide who was paid to bring the families to the transit camp, from which point we hoped to reach Israel. “I remember how at a certain point the doubts and rumors started among the adults, about how the guide did not want to go on, that he wanted more money.”

From an early age you are told that Yerusalem [Jerusalem] is a land made of gold and precious stones. That was an inconceivable dream, which spoke to me as well, a small child. That is the dream which gave me the strength I didn’t even know I had.”

The guide ultimately deserted the families, and abandoned them to their fate. Because of this they did not manage to reach the transit camp. Many days after they were abandoned, they managed to reach a Sudanese camp run by the Red Cross, and while they stayed there, Operation Moses was beginning in northern Ethiopia and southern Sudan.

The discovery of an Israeli presence on Sudanese soil turned the Sudanese very hostile towards the Ethiopian refugees. “One day, Sudanese soldiers entered the camp with large trucks and pickups and took everything that could be found. Some of the people were executed, and others were evacuated. To our fortune, we were registered with the Red Cross as refugees from Ethiopia. In the camp there were thousands of people, mostly non-Jewish, mostly people who had fled from the war and the famine that raged in Ethiopia.

“That intense heat of Israeli summer, that’s winter compared to what it was like there. I’m talking about temperatures of 44-45 degrees [Celsius]. The conditions were extremely tough. In the camp many people had malaria, mostly children. One of the children, my cousin, passed away there.”

The whole group of 54 people from Ayasa’s village were crammed into trucks by Sudanese soldiers and sent to a military camp. “That became our prison for the next 5 years. Each family received a shack which fit 8 people. They were hard years of interrogations, abuse, and torture, for the adults and the children. The soldiers were watching you all the time.” Ayasa describes a difficult reality which included public humiliations, and constant fear that you or your family would be harmed.

“I get asked what my biggest war from that whole time,” says Ayasa, and is reminded of his family. “I remember one time where one of the soldiers was drunk. He came up to our shack, grabbed my big brother, and put his gun against his shoulder, aimed the barrel toward him and tried to shoot. My father jumped on him to protect my brother. After that he was taken in for questioning and was beaten badly. I was sure that I would never see him again.

“I was also beaten; all the soldiers were two meters tall with giant arms. What’s a small 5 -year-old kid next to a soldier like that? All you had to do was say something incorrectly, and you were immediately slapped across the face, which would make my whole head ring. I remember the feeling of fear. They were hard years. A person convicted of a crime receives a sentence, 15, 20 years, and he knows that now he’s got to wait for the time to pass. We did not know when this would end, we could only pray and hope every day that it would pass.”

“Bargaining” with Mossad agents

According to Ayasa, throughout the entire time the families were in communication with Mossad agents who instructed them to not identify as Jewish under any circumstances. “We told the soldiers that there was famine in Ethiopia and that we came to earn a living in Sudan. The whole time they never knew we were Jewish. If they would have found out, we would not have been kept alive.”

If it was forbidden to be Jewish, how did you preserve the customs, or even keep kosher?

It was a great challenge. The Sudanese eat bird meat. That’s not kosher, obviously, and we also feared that they would poison us, and so we only ate what the Red Cross would bring. They would bring us flour from which we made injera [Ethiopian fermented flatbread], and that was it. For five years – breakfast, lunch and dinner. I clearly remember the first egg I ate, in the Sudanese city of El-Gadarif, after they let us go, after five years of not eating a single one.”

We told the soldiers that there was famine in Ethiopia and that we came to earn a living in Sudan. The whole time they never knew we were Jewish. If they would have found out, we would not have been kept alive.”

In their fourth year of incarceration, police officers arrived at the camp, replacing the soldiers, and conditions improved slightly. For the first time, they permitted Ayasa’s family to go into the big city, to roam the streets and go shopping.

“Shopping is great, but where would we get the money? What happened is that Red Cross staff would bring us clothes and Mossad agents would meet us on the street. My father would shout: ‘5 shillings! 5 shillings!’ like a salesman. An agent would approach him, they would ‘argue’ over the price, and then the agent would hand over money and letters with messages. That allowed us to buy some things. It wasn’t enough to go out in the city, but I remember how all of a sudden my parents would bring us watermelons and bananas.”

We knew we could survive this, that it would pass”

Did your time at the camp change you?

“I don’t know if this is a good thing or a bad thing, but I grew up very quickly. Indeed, those nightmare years were when I was 5 – 8 years old, but my thoughts and feelings were those of an adult. I remember that we would sit, the whole family all cramped together, and I would hear my parents’ ideas and plans. It was impossible to find somewhere to speak alone because the Sudanese would punish you. We grew up without intending to. We gained an inner strength that will stay with us our whole lives.”

What gave you that strength?

“Despite the great difficulty, we knew we could survive this, that it would pass. I was sure of that. The prayers of the Kesim who prayed for us, and that at some stage we found our that we had more family in Sudan who were waiting to reach Israel, that there had been a huge operation, ‘Operation Moses’ to bring in many Jews. It felt as though something big was happening in our favor which gave us the strength to go on.”

We saw the light, and then came the black darkness of Egypt”

After five years of waiting, one day, a truck arrived. “A police officer got out and said to us: ‘you are free.’ We asked – ‘where do we go?’, and the policemen answered, ‘You came from Ethiopia, so we’re taking you back, to Addis Ababa.’ We were in the truck for two horrible hours of stifling heat and suddenly – they threw us out onto the dirt. Nothing happened, it was a trick intentionally designed to break our spirits. I remember it perfectly. They told us we were free, and we had already seen the sunlight and then came the black darkness of Egypt. Only half a year later, the real truck did arrive.”

I grew up very quickly. Indeed, those nightmare years were when I was 5 – 8 years old, but my thoughts and feelings were those of an adult.”

A different Sudanese police truck took the families to Khartoum, and from there, back to Ethiopia. After a long wait of eight months, in January, 1991, Ayasa’s family received permission from the State of Israel to make aliyah to Israel. “The whole time we asked why Israel had not done anything. The camps we were in were outside of the city, and it would have been possible to rescue us. We never got a real answer. To this day I do not know why we had to wait there such a long time.”

When they reached Israel, moments before the Gulf War, Ayasa and his family settled in Arad, and soon after moved to Beer Sheva. Ayasa finished his studies, served in the army, and today is married and the father of four. After five long years of religious studies, he was certified as a Kes.

The 4,500 who perished led the way to Israel for us”

8,000 Jews made aliyah in Operation Moses. Some 4,500 Jews perished during that period on perilous journeys from Ethiopia to Sudan and in camps, and 1,500 remained in camps in Sudan and made aliyah only a number of years later.

“This is the story of people whose deathled the way to Israel for us. In their honor the Israeli government opened up diplomatic channels with Ethiopia. If not for them, tens of thousands of us would have died on the way to Israel.”

Do you think that Israeli society recognizes what you and your family have gone through to reach Israel?

Young people do not know the story. When I meet with them and speak with them, they are completely stunned at how a person can walk for a month on foot, barefoot, through the desert. And there is also of course the mental suffering and trauma which follows you for the rest of your life. When we got here nobody offered us social workers or psychologists. Quite the contrary, we had to prove that we were imprisoned."

“I am recognized as a Prisoner of Zion, but in order to get the status and benefits you have to fill out forms, which I have not. People who have been imprisoned for a month, two months, fill out the forms and receive benefits but I have no energy for those questions. The government ministries should verify that I was in prison because all the names were written down, should I prove to them what I’ve been through?”

“And there is also of course the mental suffering and trauma which follows you for the rest of your life. When we got here nobody offered us social workers or psychologists. Quite the contrary, we had to prove that we were imprisoned.”

Despite his anger over the lack of recognition on the part of the government, Ayasa is filled with meaning each time he meets with young people to tell them his aliyah story. Recently, he finished writing down the stories of members of his family and village, and he hopes to find an editor who will agree to edit them. “the young people I meet are dying to know, and already are passing it on. We must remember, write, memorialize and tell the story. People should know that we are here in Israel, and rightly so. Each family that made aliyah has its own story, even those who weren’t imprisoned or Prisoners of Zion. Every oleh has a family member who made the journey, who made it through the suffering, the hardships and the hunger.”

Alongside Ayasa sits Lior, his second son, who has just celebrated his twelfth birthday. “Each and every time that Dad tells me these stories, I feel like I understand how they did it a little more. I tell myself: ‘OK, I think I get it.’ And then, it doesn’t make sense again. It’s unbelievable, what they did. When he was my age it was already all behind him. It’s an amazing story that Dad became a Kes after all he went through. Iמ the future I really want to tell this story to our generation and to those to come. I am sure that they would be both proud and astounded like me.”

I tell Lior and the rest of the kids: That was me there. That’s my story, our story. It’s important that they understand what we went through in order to reach Israel. Will they be faithful and pass in on? That’s the educational mission.”

His little sister, Shilat, read out a letter that her father wrote to the students at the memorial event at her school last year. “Every Passover, just as we pass on the story of leaving Egypt to the next generation, remember that we too, your forefathers, left Egypt,” he wrote.

“I tell Lior and the rest of the kids: That was me there. Your Dad. Not even your grandfather, or someone from the past. That’s my story, our story. It’s important that they understand what we went through in order to reach Israel. Will they be faithful and pass it on? That’s the educational mission."

“The dream for Jerusalem is not just a dream of the Ethiopian community. It is a dream of many other communities who paid very heavy prices. Every story has its own uniqueness. It pains me to see people leave Israel. Some people are going back to Ethiopia to settle down. During coronavirus we saw suddenly how people from all corners of the Earth are dying to come back to Israel as soon as possible, and how Israel sent airplanes all over the world to bring back the Israelis. That just shows that when you’re in need – there’s nowhere like Israel. It’s a shame that sometimes we get taken for granted, it’s like they say, when things are going well – you forget.”