On a rocky hill near Tel Arad stands a large, brown and white striped tent made of goat skins. Children climb up the hill, while inside the tent, final arrangements are made for another day at this makeshift school, which is known as the Abu Judah Club.

The school opened last week. "Normally, the children attend schools in the area, especially in Kuseife [a nearby Bedouin settlement]," says Abd al-Rahman, an elder of the Abu Judah family. School closures meant to limit the spread of the coronavirus in Israel left many students in this area without a way to continue their education.

Without computers or internet connection in their homes, online learning is impossible. As is the case in many unrecognized Bedouin villages like this one near Tel Arad, phone reception is spotty or nonexistent, so students can’t connect to online classes by smartphone, either. "I need to go up the nearest mountain to get phone reception," says Muhammad Abu Judah.

Just like over 50,000 other Bedouin citizens of Israel, the Abu Judah family lives in a village that the Israeli government does not recognize as legal. Bedouins lived as nomadic farmers when the state of Israel was established in 1948. The vast majority were expelled from the new country.

In subsequent decades the government built new towns in the Negev and persuaded the majority of Bedouin citizens to move into them. But around a quarter of Bedouins living in the Negev remain in tens of unrecognized villages, like the one where the Abu Judah’s extended family opened their makeshift school.

Since villages like these are illegal by Israeli law, they are often subject to demolitions. Residents face long wait times and discrimination when they apply for building permits, and crucial infrastructure such as roads, electricity and water supply are nonexistent.

Schools in unrecognized Bedouin villages have been under-resourced since long before the coronavirus pandemic. The Abu Judah’s village is under the jurisdiction of the Al-Kasom Regional Council, in the northwestern Negev. Throughout much of the last year, the Al-Kasom Regional Council faced off with Israel’s national Education Ministry in an attempt to gain an official budget for schools in the unrecognized villages.

That lack of resources is having consequences. Last year, students from Bedouin communities in the south of Israel recorded the lowest standardized test scores in the country. Israel as a whole recorded the largest educational gap of any OECD country, between Hebrew-speaking and Arabic-speaking students. At the time, the Education Ministry promised to focus on improving education for Bedouin students in the Negev region in the south of Israel.

Now, amid the pandemic, residents of this unrecognized village are taking their education into their own hands. "The idea came from one of our university students, who started teaching four or five kids in a small room, with no Zoom and no internet,” says Muhammad Abu Judah. “I saw, I was impressed, I built a tent, and we started."

"The children are overjoyed, because they are tired too"

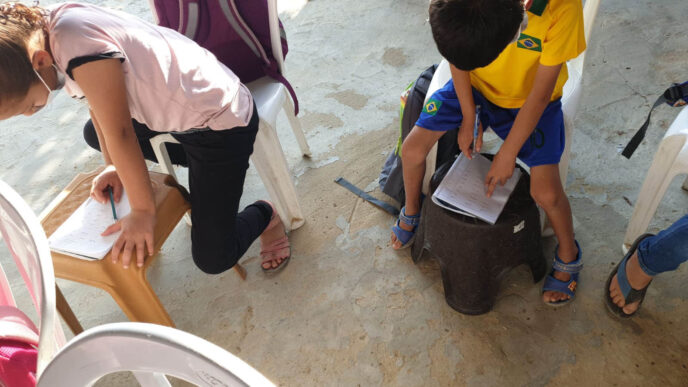

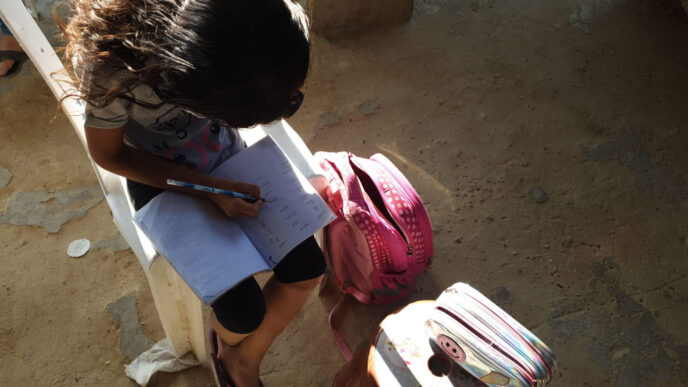

In the tent, some of the children sit on plastic chairs and some on rugs or mattresses spread out on the scrubbed asphalt. Off to the side stand several erasable boards. The children are divided into learning groups of four or five students, by age. Some sit inside the tent, some outside, and another group is in a small room next door. Some sit around a table, while others lean over books spread open on their knees. The teachers rotate between the groups.

"The teachers here are all from the extended family, we all live in the neighborhood," Muhammad Abu Judah says, explaining how the club operates less formally than a traditional school. "They say, 'I’ll come at eight,' and some come at ten."

Abu Judah, a teacher of special education and mathematics, says that the students will receive enrichment in Hebrew, English, mathematics, and Arabic.

The houses of the Abu Judah family are scattered around the hill. In the distance are the houses of Kuseife. It is very hot in the tent, but the children and adults are careful to wear a mask and maintain the required distance.

Abd al-Rahman looks at what is happening in the club, with a big smile on his face. "It saves the kids and saves their parents," he says. "Every day I would see the kids running in the field. They have no electricity here, no computers, so they would run and fall and cross the road dangerously. Now that we have this little school, they are overjoyed, because they are tired too."

At 10:30, everyone goes out for a break and eats food brought from home. A few minutes later, the children gather again for creative activities and crafts until noon. "They return in four groups, if there is anyone who will sit with them," says Muhammad Abu Judah, who seems tired from a long day of teaching.

"Hopefully more parent-led initiatives will start up”

On the opening day, the children dress up for their impromptu class. Muhammad and the rest of the teachers were waiting for them in the tent. The head of the Al-Kasom Regional Council, Salameh al-Atrash, brought basic equipment: tables, chairs, pencils, and notebooks. He promised to bring more comfortable chairs.

"Take advantage of this special opportunity," Al Atrash told the students, "and remember that each of you can, if you want to, be a doctor, a scientist, or an astronaut."

Al-Atrash says he would encourage other parent-led initiatives in the Al-Kasom Council’s jurisdiction. He says that parents are concerned. They are trying to reduce the children’s learning gap. So, they are taking advantage of the fact that many of their family members are teachers. "I hope that the Bedouin Authority will not harm this initiative and that more such initiatives, led by responsible parents, will start up," he adds. The Bedouin Authority is a government organization headquartered in Be’er Sheva.

Muhammad Abu Judah agrees. "I am waiting for the Minister of Education to come and see our conditions," he says. "We maintain all the conditions of the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Health, wearing masks and in groups of four or five."