Labor organizers Miko Tzarfati and Keren Ofek are each fruits of starkly different Israeli societies. In the twenty years that separate their generations, Israel’s labor market underwent seismic shifts, and with the realities of working life, social perception of the union shifted as well.

When Miko Tzarfati first joined the Israeli Electric Company union, Israel was still a case study of a progressive society and boasted low rates of inequality. The government, however, adopted an aggressive neoliberal agenda in the 1980s. It privatized industries and cut public spending, which led to a decline in the middle and working class' share of income.

In 2011, social justice protests rocked Israel, creating greater awareness of economic inequality. In the past decade, over 200,000 workers have unionized, and income inequality has dropped steadily. This renewal had a personal impact on Ofek, whose inspiration to become a union organizer came from the 2011 protests.

Tzarfati is 62 and has worked at the Israel Electric Corporation for almost 40 years. The Electric Company is one of several formerly public companies that the Israeli government voted to privatize in 2015. He’s served on the workers’ committee since 1994, and has led the committee since 2003. He represents nearly 20,000 people, including the company’s retirees.

Ofek is 42 and works for Partner, a telecommunications company in Israel. She’s worked there since 2007 and helped lead the effort to unionize the company’s 3,000 employees in 2014. Partner’s unionization was part of a wave of unionizations of communications employees, including at major companies Cellcom and Pelephone. She’s now the chair of the workers’ committee at Partner.

Ofek and Tzarfati had only met in the hallways of conferences before they joined Davar for a joint interview. Their stories shed light on the challenges and success of Israel’s labor movement over the past several decades, and what the future might hold.

Miko Tzarfati – 1980s

What inspired you to get involved in union organizing?

Tzarfati: "I do not define myself as a member of a workers' committee. I am a socialist at heart because that’s how I was raised. Growing up, we valued equality."

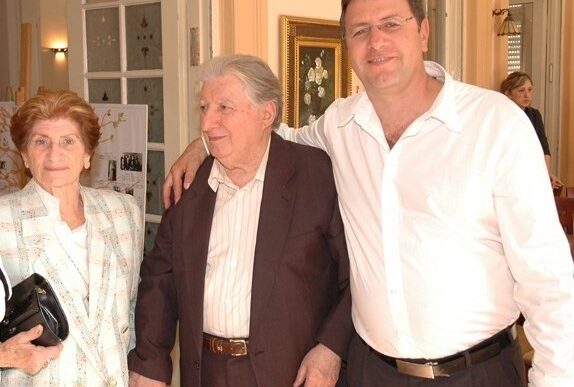

"I grew up in a very simple house. My father, Rafael, was originally from Thessaloniki. He was a Holocaust survivor and worked at the Tel Aviv port until it closed. Then he worked casual jobs. My mother, Tzila, was a housewife all her life. We grew up in North Tel Aviv, and I shared a bedroom with my two brothers. We were very happy."

"When I was growing up, you couldn’t tell which kids belonged to which family. The daughter of Ernest Yefet, the CEO of Bank Leumi, was part of the same youth movement as me – the Machanot HaOlim. No one would have been able to distinguish us or our siblings. We lived in an atmosphere of equality. No one was above anyone else, everyone shared with each other, and we were happy. When Likud came to power in 1977 and privatization, American influence, and consumerism increased, the socioeconomic gaps in the country began to grow."

It sounds like Israeli society was a lot more equal back then than it is today.

"There have always been socioeconomic gaps in Israeli society, but there have also been periods when society was more equal," he explained. "In recent decades, economic policy has changed and the gaps have grown."

"Over the years, I saw how the Histadrut went from a strong and dominant force in the country to an out-of-touch organization that was in danger of not existing at all. When I was growing up, in the 1960s and 70s, I didn’t really care about unionization because of how the Histadrut was operating at the time. There was a culture of “protect me and I’ll protect you.” I grew up feeling very antagonistic toward that."

So how did you get involved in union organizing?

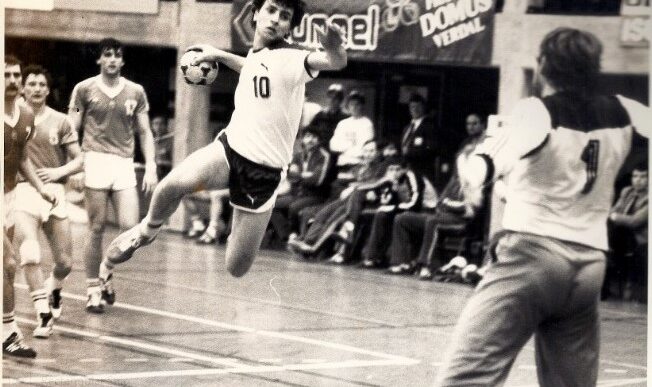

"The late Yoram Oberkovich, chairman of the legendary workers’ committee at the Electric Company, was my handball coach. I was the team captain, and because he knew me as a leader on the team, he wanted me to work at the Electric Company. I learned a lot from him.

"Eventually he asked me to join the union activities at the Electric Company. He said to me explicitly: “Miko, I need you.” After I joined, I slowly encountered all the issues that the IEC was facing. I soon felt like the company’s problems were my problems. I was slowly drawn into this world. I realized I did want to address the existential problem facing the Electric company."

"In the 1990s, the Israeli government ended the Israel Electric Cooperation’s exclusive right to provide electric power in Israel, which dated back to the British Mandate. Then they wanted to dismantle the company completely, even though there was no economic or political reason for doing so. Of course, this was an attack on the livelihoods of tens of thousands of workers. That showed me how much the Histadrut had declined, how much it was suffering from bad publicity.

"At that point, the Histadrut had a public image that was created in the times of Yehoshua Peretz and the militant strikes in the port of Ashdod in the late 1960s."

Despite his criticism, it is important for Tzarfati to show respect to the organizers that came before him. "I do not say this to condemn those labor committees, but rather to point out that they were outdated organizations. They were brutal, in a way that caused damage to the state. When I took over the leadership of the organization, I decided to take a different approach. I couldn’t change the dynamic overnight. But I at least tried to make sure that my colleagues at the electric company understood the benefit of being unionized."

It sounds like you went through a dramatic shift, from antagonism toward organized labor to assuming the leadership of a strong union. How did that happen?

"The story of the closure of the Ata factory and the workers' struggle there had a big impact on me. [Ata was a major textile and clothing company in Israel.] Everyone knew Ata and wore Ata's clothes. The late Pini Grove was the chairman of the Ata labor committee, a man of strong values. In 1985 they wanted to close Ata. The factory and the workers went on a big strike. They received a lot of attention in the press. They hated and slandered Pini. In the end, Ata went bankrupt and they closed the factory. Then they interviewed Pini. He appeared on TV and cried. Suddenly he got sympathy from the public."

What did you learn from that?

"I thought to myself, 'It's better to be hated for being strong and taking care of people than to just give up and get a bit of sympathy. I learned you have to fight for the people.”

Keren Ofek – 2011

What about you? How did you get involved with union organizing?

"My story is different. I grew up in Givat Sharet in Beit Shemesh. My family was politically conscious and leftist. Our Polish roots showed. We rested every day from two to four p.m., my mother made sure we read books. My political education started from the time I was young. Principles, values, norms – they were part of my upbringing. My mother, Lilach, is a teacher, and my father, Haim, is a small business owner."

Did your upbringing influence your choice to be a union leader today?

"I don't think there is a connection, but I have a story from high school that shows how I got started. The summer before 10th grade, my mother thought I should take the final language exam. She and her friend prepared me for the test, butthe school refused to let me take the exam (which is typically administered in 11th grade).

"When I started 10th grade, I was bored in language class because I had already studied and prepared for the test. Our teacher was not very good and I would correct her all the time. I felt it was impossible to continue, she taught so poorly and it ruined the class. One day I said to the other students, 'Don’t enter the classroom, sit in the hallway.' The teacher came and called us in to class, and I told her: 'No one is going to enter the classroom. Don't even try, it's a waste of your time.'”

Did you get in trouble?

"Of course they called me to the principal's office. I sat with the principal for three hours, talking about motivation and ambition, about life, and in the end the teacher was replaced. I didn't even get a suspension."

How did you start working at Partner?

"I studied electronics and was hired by Partner as a contractor employee. When I was hired, my mother said, 'Just join the company and be nice to everyone, don't do anything.' That's how I worked for two and a half years. Being employed like that was relatively okay, but I felt like a second class worker. On holidays, they would tell the employees chag sameach and give them gifts, but not to me. I did not think I would stay at the company for so many years.

"I did not know about the Histadrut, except for my grandma's stories about having a red member’s booklet. I did not think I would form a union, not at all. Employees, labor law, benefits, what is and isn’t included in a pension plan – the more I was exposed to labor organizing concepts, the more I fell in love."

So what motivated you to start organizing?

"The big protest of 2011 started a wave of unionizations. Visa CAL was the first, followed by Pelephone and Clal Insurance. At Partner, we saw what was happening and we wanted to do it too. The social climate at the time led us to unionize. Another thing that motivated us was that at that time, employees felt that management was unfairly targeting some workers for dismissal.

"Kahlon's reform in 2011 also pushed us toward unionization because it lowered the profits of the cell phone companies, and the workers were the ones who paid the price. [Moshe Kahlon, a Knesset member at the time, initiated a reform that increased competition and lowered consumer prices for cell service.] A lot of workers were fired. If Kahlon’s reform had taken the workers into account, then maybe it would not have gone that way.

"We decided to set up a committee. The guys told me, 'You’re the only one who's got the balls for this, go make a committee.' I never thought I would be a leader, on the contrary, I thought I had no talent for anything. At 16, I was terribly frustrated that I hadn’t found my calling. I guess I found it late."

Tell us about the process of unionization at Partner.

"From August 2013 to March 2014, we brought more and more people into the Histadrut, without declaring that we were forming a union. At that time around 5,000 employees worked at Partner. On March 3, I hurried out of work to get to my daughters, and my manager, then-CEO Haim Romano, called me and gave me a letter calling me to a disciplinary hearing. The next morning, the management received a letter from the Histadrut that we had formed a union and that they needed to withdraw the letter. They withdrew the letters of dismissal and we formed a union.

"It was one of the hardest times of my life. Now, because of the coronavirus, I cannot say it was the hardest time, because now it's harder. When we unionized, my husband was in the army, so he was less available at home, except on weekends. My family helped, but I was alone. It was a very difficult time, but I decided to do it, going head to head with management.

What was particularly difficult?

"We were facing war. Haim Romano actually set up an army in front against us. This was after the Pelephone ruling [the National Labor Court ruled in 2013, following a Histadrut lawsuit, that an employer is not allowed to oppose the initial unionization of its employees]. Finally in September Romano agreed to meet us. And in the end, after a year and a half of negotiations and two months after he left, we signed a collective agreement."

What gave you the strength to keep going?

"I did not take no for an answer. I kept imagining how what I was doing could improve my daughters’ lives in the future. It probably came from my upbringing, the idea that nobody can tell me what to do. I am the one who says what to do, I don’t just go along with the crowd," concluded Ofek.

Generational changes and challenges

Tzarfati: "I think that one of the most important things in building a union is that workers identify with the workplace. [Turns to Ofek]: In the kinds of workplaces you are unionizing, the employees are from Generation Y, they’re not that interested in building an identity around where they work. It’s a lifestyle that I don’t really know how to deal with.

"When I talk about unions with my kids, working in the high-tech industry, they look at me like I’m crazy. Of course, they don’t yet know what it’s like to be in their forties. Right now they are young and beautiful and successful, but life is not always going to be like that. It’s their choice, and I am happy with their choices. But I am confused about how to educate the new generation.

"I feel I have to strike a balance between the current reality and the values I believe in. I believe that a feeling of belonging, of security, can really add value to someone’s life. We have to find a way to navigate the fact that some workers want these things and some really aren’t interested."

Ofek: "I think in the Partner union we have found ways to deal with the generational changes, but it’s hard. The young workers you’re talking about don’t know what I mean when I talk about pensions, but when I tell them we’re having a Purim party they’re quick to sign up.” When we show concern for the workers’ wellbeing, it creates a new kind of loyalty. They think, “you give me something, so obviously I'm with you.”

Union leaders during a pandemic

Ofek: "The year 2020 is the hardest thing I’ve gone through as chair of the committee, even though more and more I feel that 2021 will be even worse.

"Deciding to furlough people is inconceivable, quite the opposite of asking them to work remotely from home. It’s difficult to decide to create pods that make people feel disconnected and lonely. Apparently there has been a 700% increase in calls to aid centers. Some of our workers are among those in need of aid. If your husband is self-employed and not working, or your wife is in the hospital, where are you going to get money? This is the scariest year I've ever had."

Tzarfati: "These days people understand the importance of a union more. Fortunately, in the electric company everyone is considered an essential worker and everyone works. It’s at times like this that people understand the meaning of working in an organized and strong workplace that can make sure workers have what they need.

"Even the political leaders understand that there is no choice but to work together and protect workers. The whole world understands this. Maybe in this respect the coronavirus will help reign in all the reforms."

Histadrut – the next generation

Tzarfati (to Ofek): "I think the work you’ve done is more valuable than what I did as a union organizer. I was born into a union tradition that goes back to the early days of Labor Zionism. I had to preserve it and innovate a bit. But you created a union from scratch, which is much harder. You did a wonderful job and it makes me so proud.

"Keren, I see in you and in women like you, the generation that already holds the baton. I already feel passé. I feel I have to retire. I am 62 years old, I’ve worked with the management of the Electric Company, the Histadrut leadership, and the state leadership in Israel. All the reforms that have taken place to date still haven’t reduced the size of an electricity company by more than a tenth, and I see this as a great thing that I have been able to do. Now I need to make room for the next generation."

Ofek: "Miko, you are amazing, and I am thrilled by your kind words. It is my privilege to be here and speak with you."