Disabled people who work in sheltered workshops are employees and as such are entitled to basic workers’ rights, the National Labor Court declared last Sunday in a precedent-setting ruling. Sheltered workshops employ people with disabilities, usually in a separate work environment and with exemptions from labor laws, with their stated goal being “rehabilitation” of the disabled people into the workforce.

In the ruling against Matash, an organization that operates rehabilitative employment centers for people with disabilities, plaintiff Haim Zer was recognized as an employee, which entitles him to a pension, vacation pay, severance pay, and compensation for lack of a pre-dismissal hearing. He was awarded a total of 20,000 shekels (about $6,200.)

“The right to work includes the right to equal and active participation in society, to live independently with dignity and to realize the abilities of the working person,” stressed National Labor Court President Varda Wirth Livneh. “It’s a legal obligation on the part of the employer. This is the law, and they are not above the law.”

The plaintiff, Haim Zer, was referred to a rehabilitative employment center in accordance with the decision of a committee of the Ministry of Health. He worked for Matash for nearly 12 years, with a rehabilitation allowance of between 11 and 13.5 shekels per hour (about $3.40 to $4.20 per hour). The minimum wage in Israel amounts to about 29 shekels per hour (about $9 per hour). At the end of his employment, Zer filed a lawsuit with the Labor Court, claiming that there was an employee-employer relationship between him and Matash and that his rights as an employee had been denied.

“Serious concern for the violation of the appellant’s right to dignity”

Matash and the state, on the other hand, argued that there can never be an employee-employer relationship between a disabled person and a sheltered workshop, because the purpose of the relationship between the two parties is that of rehabilitation.

The ruling held that “the recognition of the appellant as an ‘employee’ does not have a purely economic significance. The fact that the appellant was paid for years at an hourly wage of 13.5 shekels (including a bonus, otherwise he would have earned only 11 shekels about $4.20 per hour), while it has not been proven that his ability for employment was less than normal, presents a serious inconvenience and raises deep concerns about the right of the appellant to respect and to live with dignity.”

Oren Hellman, founder of the Equal Opportunity Initiative for the integration of people with disabilities into the labor market, told Davar that he was familiar with cases of disabled workers being paid between three and four shekels per hour (between about 95 cents and $1.25).

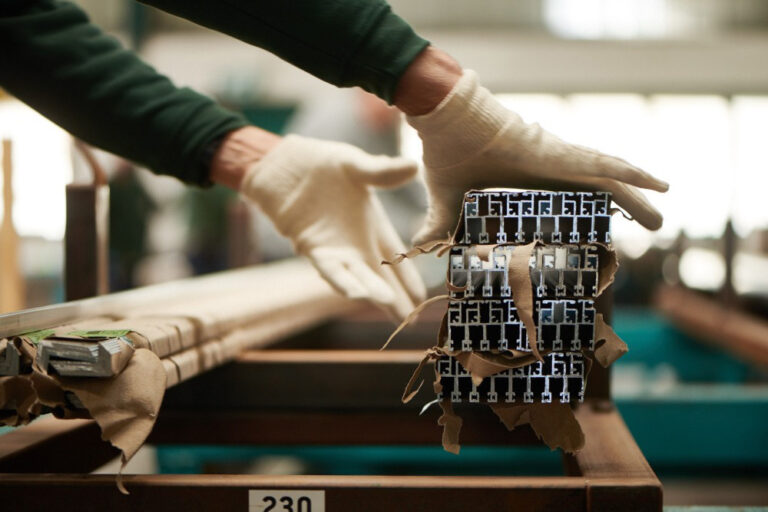

“In one case, a mentally disabled employee who worked in the production of jewelry in a sheltered workshop, told me that the products she produces are sold for thousands of shekels but she receives a few shekels per hour,” he said.

Judge Sigal Davidov-Mottola, who wrote the majority opinion, stated: “Even if the sheltered workshop is a unique enterprise and a framework that has several objectives in keeping with the state’s commitment to take active steps to integrate people with disabilities into the labor market, it is still an enterprise whose characteristics are sufficiently similar to a job in the free market.”

Sheltered workshops represent an “employee-employer relationship”

“The claim that a person who worked for the advancement of the sheltered workshop, came in every day and worked, is not entitled to the basic protective rights granted in the relevant laws, simply because in light of his disability he did not fit the free labor market, and therefore all his work over the years merely ‘resembled’ work and was intended entirely to teach work habits and get to know a normative work environment — in my opinion, this is not in line with the basic principles of the Equality Law,” Davidov-Mottola said.

According to Davidov-Mottola, there is nothing from a legislative standpoint that would impede the recognition of a sheltered workshop as a workplace where an employee-employer relationship exists.

“Sometimes the relationship has more than one goal — in our case, a dual employment and rehabilitative goal. The employment goal is itself enough to establish an employee-employer relationship,” she explained.

Only when the evidence shows that the employee’s contribution in a given case is marginal, when the work component is negligible compared to the rehabilitation component, can it be determined that a disabled person is in fact not an “employee.” This was not proven in Zer’s case.

The ruling further emphasized that “the very fact” that the current economic model “of any sheltered workshop is based on the possibility of not providing its employees with basic protective rights — certainly does not justify claiming that a disabled worker in a protected enterprise is not for all intents and purposes, an employee.”

“The current ruling of the Labor Court is excellent, but it is not enough”

Disability activists such as Hellman are pleased with the court’s ruling, but feel that it needs to go even further.

“There is no equality in the labor market, there are those who receive higher and lower wages, but there are also basic rights that every person deserves to receive. These [disabled] people have been excluded and deprived for years,” Hellman said.

Hellman described how the sheltered workshops that were established in Israel in the 1950s and 1960s, when the treatment of people with disabilities was different. According to him, this led to the establishment of a norm whereby people with disabilities work under an ostensibly rehabilitative framework but in effect, work for many years without basic rights in frameworks that do not even integrate them into the general community.

“The current ruling of the Labor Court is excellent, but it is not enough. The ruling gives an important message, but these are things that will require changes in legislation,” he said, noting that although the court has recognized the obligation to uphold workers’ rights, it has said that sheltered workshops are still not obliged to pay their workers minimum wage.

The sheltered workshops were designed to provide vocational rehabilitation: training, teaching of vocational skills, accompanying and providing placements for workers who were supposed to advance from the workshops to eventually work in the general community and the free labor market. But critics say they have not lived up to this goal.

“In practice, what happens is that people get stuck there for decades, and those who run the workshops have no interest in them advancing,” Hellman said. “What needs to happen now is legislation that will limit how long a person can be employed in a rehabilitative setting in a sheltered workshop, and in particular will create incentives for such workshops for the quality placement of workers in the general labor market.”

Hellman made it clear that he is not in favor of closing the sheltered workshops, nor does he believe they will close.

“I do not want to throw the baby out with the bathwater,” he explained. “If the sheltered workshops close tomorrow, it is clear to me that people will be out of work and have no frameworks for employment, but I am definitely in favor of reducing them.

“A lot of money goes into [sheltered workshops] and perhaps that money needs to be invested in incentives and adjustments for employers in the free market that will encourage them to employ workers with disabilities, or in individual support and training for disabled people in regular workplaces.”

According to Hellman, blind people are referred “very easily” to sheltered workshops, and often work in them for many years. He recounted a recent visit to the Jerusalem School for the Blind.

“I met brilliant, intelligent and talented young people, and I tried to understand why such young people are actually forced into monotonous work in sheltered workshops earning below the minimum wage,” he said. “Why shouldn’t the state invest more in them and encourage them to pursue academia, a profession, a respectable job?”

“It’s important to understand that these are good, productive people like any other person," Hellman explained. “They are not employing them as a favor.”

This article was translated from Hebrew by Leah Schwartz.