“I think a lot of people, especially young people, can find in cooperatives an answer to the needs of their generation,” says Dr. Orna Shemer (51) from Moshav Arugot, a researcher at Yad Tabenkin and the School of Social Work at the Hebrew University. “This is a model that embodies discourse, values, security, employment, friends and the community.”

According to her, a cooperative is generally defined as “an independent association of human beings, who choose to advance their economic, social, and cultural needs and aspirations through joint ownership of a democratically run business system.”

In her research, published in the book “Cooperation in Israel: Past, Present, Future,” Shemer reviews the new wave of cooperatives in Israel, “most of them [being] relatively small and communal,” she says.

“Most have social goals and other values such as sustainability, fairness, local economic development, which connect very much to collaborative ideas in the world,” she continues.

Shemer examined the community guidelines or bylaws of some 20 cooperatives from various fields: consumerism, transportation, mental health care, education, housing and more, most of them established after 2011. Her research is based on meetings with members of three cooperatives: the sound production cooperative “Shomim Chazak” (Hearing Loud); the Jerusalem consumer cooperative “Shelanu” (Ours); and the “Tarbush” cooperative, established by a group of artists in the city of Sderot with the aim of developing local arts and culture.

An attempt to build an alternative economy

According to Shemer, the local community plays an important role in the global cooperative movement.

“Unlike the large cooperatives of the early days of the settling of Palestine in the early twentieth century, which grew out of the hegemony of labor, these new cooperatives were formed just after the social protests of 2011," she says. "They grew out of a protest movement against the existing system, in an attempt to a build an alternative economy.”

Shemer points to rising instability in the workplace as one of the main motivations to found or become part of a cooperative.

“The job market is changing, and more people are being pushed into weak or precarious employment situations as freelancers or gig workers,” Shemer explains. “This necessarily means they have to switch between many jobs, and leads to instability.”

According to her, a cooperative creates a sense of security and stability because of the high levels of partnership between people. And when members pool their resources together, they can reduce additional costs as well.

“The cooperative model revolves around collaboration and partnership. Members divide the collective work fairly amongst themselves, make decisions together and share responsibility for managing the business,” Shemer says. “It is a model that can give some degree of certainty and stability that has practically disappeared.”

Shemer found that within the cooperatives she researched, most of the members were younger, mostly between the ages of 25-45.

“This is a generation that is facing a complex economic reality, with of the dissolution of the welfare state and the stable employment structures that characterized the generation before it,” she explains. “This destabilizing phenomenon happened along with general price increases (on consumer goods) that make it difficult to establish a reasonable life here [in Israel].”

This difficulty that young people face was a common thread that arose in the interviews Shemer conducted.

“What is interesting about the new cooperatives is the emphasis that is placed on the individual,” she says. “The realization of the collaborative idea allows for more individual expression.”

“What really stood out to me was the emphasis on flexibility, openness, ideas of horizontal democratic processes around discourse and dialogue,” she adds.

In her research, she admits, most of the people interviewed came from a middle-class socio-economic background. But in Israel, Shemer says, there are also cooperatives of security guards, shepherds and cleaning workers. And in the past, there was a phenomenon of a factory owned by its workers.

Shemer would like to see more cooperatives uniting working class populations.

“I think this model serves as a good solution for addressing poverty and other difficulties with making a livelihood. And at the macro level, perhaps it is also a solution to the unemployment crisis we are in.”

Hamifletzet: “An initiative of the residents”

Gal Eblagon (34) was exposed to the world of cooperatives some six years ago, when she moved to the Kiryat Yovel neighborhood in Jerusalem.

“After I finished my university studies, I was looking for a place to live that had something to offer young people,” she says. “And more than that, I was looking for a community.”

Eblagon found out about the cooperative bar “Hamiflezet” (the Monster) via a Facebook post.

“I was fascinated by the fact that there was a place set up at the initiative of the residents. Hamiflezet met my need for being part of a community,” she explains. "I showed up once to buy a drink, and the next thing I knew, I was pouring the drinks myself on shift, as a volunteer.”

After that second visit, Eblagon soon joined the leadership of the cooperative and for the last two years, she has served as its chairperson.

The cooperative bar was formed in 2013 when a group of friends from the neighborhood were looking for a place to sit, drink and meet new people. Over the course of three years, the group hopped between different spaces in the neighborhood, meeting at cultural events, music concerts and other meet-ups. Eventually, the group of founders expanded to the point where they needed a more permanent solution.

“After three years, we reached out to the community leaders in the Yuvalim neighborhood for assistance [in finding a permanent place], and we were given a space in the backyard of the community center,” Eblagon describes.

“We renovated the place ourselves – we leveled the area, built up the infrastructure, and that’s how the pub was built.”

Today, Hamiflezet has about 200 members, from young people who have just finished their army service (20-21 years old) to elderly people above the age of 80. Members are required to purchase a share for 1,000 or 300 shekels ($322 and $96 respectively), and to commit to 12 shifts a year to complete the process to be full members.

“Those who join,” says Eblagon, “are coming to connect with the people, the place itself, and with the broader idea of community that Hamiflezet represents.”

“An ideological choice”

“To me, the essence is the choice to take an active role of the community, to take responsibility for the space in which we live,” says Eblagon. “Cooperation is an ideological choice, not just an economic one – on a theoretical level we are choosing to run this place as a social business comprised of full responsibility of its members and the possibility of new people joining and shaping it.”

In recent years, the cooperative has seen other new cooperative businesses around the city being established as part of a program through the Jerusalem Municipality’s Business Promotion Division. And a fifth cooperative pub is soon expected to open.

“We’ve recently began hosting a series of lectures on cooperation at the bar,” Eblagon says. “It is a model that is important for us at Hamiflezet to promote and educate about.”

According to Eblagon, places like Hamiflezet allow the average person to increase control over their life.

“It allows us to go beyond the binary in which we are either consumers or service providers. On an economic level it also opens up a lot of beneficial options for us.”

“Cooperatives can address the cost of living”

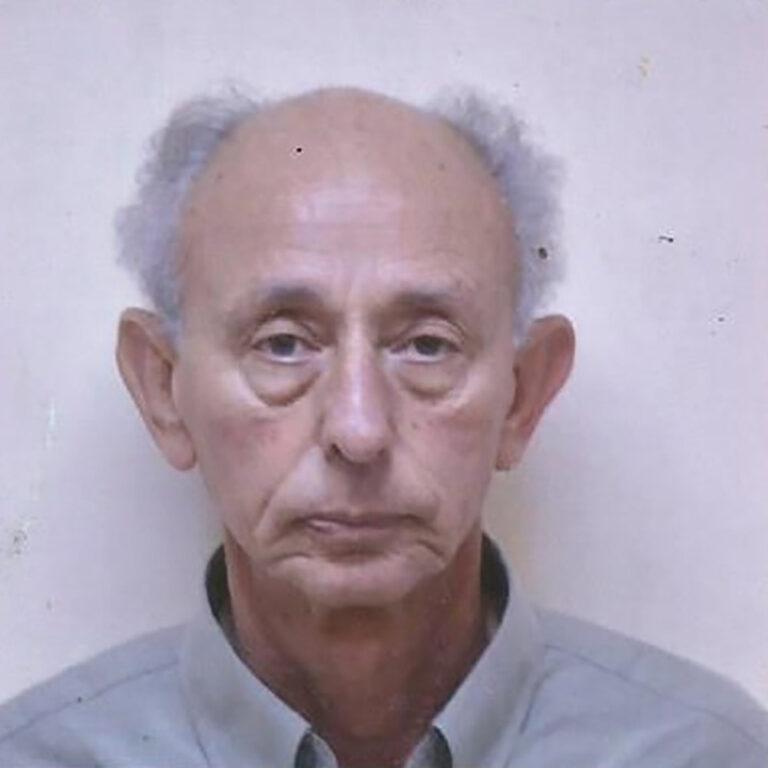

“It can be said without exaggerating that the cooperative established the state of Israel,” says Dr. Menachem Topel, from Kibbutz Kissufim, a book editor on the subject. “Many countries, especially from the developing world, have sent people here [to Israel] to learn how this tool can be used to advance national goals and objectives.”

Alongside the large-scale cooperative initiative – embodied by the mass movement to found kibbutzim and other socialist structures – there were also hundreds of small cooperatives formed during the early days of the State, according to Topel. These small cooperatives were established by private individuals who saw the need for them in: farmers in moshavim, bakeries, taxi stations, and more.

“Cooperatives have a lot of potential, because they know how to give better solutions to the needs of people than the regular capitalist private market,” Topel says.

As an example, Topel mentions Ha’Agala, a small cooperative grocery in the southern town of Mitzpe Ramon, which “jump-started a significant drop in grocery prices in the city, when it served as an alternative to the Shufersal chain, which was the only supermarket where residents could buy their food.”

“Cooperation can address the cost of living and rising prices, as consumer cooperation can reduce the brokerage gaps in direct purchases from manufacturers,” he explains.

In the 1980s, while Topel was on a work assignment on in Latin America behalf of the World Trade Union Organization and the Histadrut, he had the opportunity to work with poor fishermen to help them form a cooperative to improve their lives.

“The fishermen would go out every day with small boats, and without modern equipment,” he says. “They came back every day with a meager catch, and had to sell it immediately, otherwise everything would have gone bad. They lived from paycheck to paycheck.”

With Topel’s help, the fishermen set up a cooperative that allowed them to purchase a 15-person fishing boat built for the high seas and with modern equipment.

“It was only after we established the fisherman’s cooperative, where everyone pooled their resources together and increased output, that two international food companies approached the cooperative to sign a contract with them,” Topel says.

“It opened a window of hope for them that their children would grow up in a new reality. For me, this is the essence of cooperatives and cooperation.”

Every cooperative needs credit

There are currently about 4,200 cooperatives in Israel, with about 120 new ones founded each year. However, around 120 other cooperatives close each year, and thus the cooperative movement fails to grow. The difficulty, according to Topel, lies in the cooperative's ability to establish a line of credit.

“Like any business that has been set up, a cooperative that is making consumer products also needs credit, and unfortunately, today it is difficult for cooperatives to obtain credit from the banks,” he says.

In order to kick-start a more significant cooperative movement, state aid is also needed.

“Many states encourage cooperatives because they understand it serves the community, aids a fairer distribution of social benefits, produces welfare and community networks that reduce the burden placed on the state,” Topel describes. “States therefore enact the appropriate laws and tax breaks that will make it easier for cooperatives to grow.”

Topel gives several more examples of cooperatives on a large scale. In the Basque Country in Spain, there is the huge cooperative federation called “Mondragon Corporation,” which includes more than 80,000 people.

“They have created hundreds of factories there that provide a livelihood, educational and cultural institutions and more,” he says. “There is also cooperative bank, which belongs to all the members and is the driving force behind the success of the cooperative movement.”

Topel also views the recent establishment of the Ofek Credit Association in Israel as a reason for optimism for the cooperative movement within Israel. Through Ofek, local development of a network of cooperatives that relies on a joint bank is possible.

Another example of a cooperative lifestyle is the Scandinavian co-housing model – a model that is currently spreading to other countries. This structure broadly consists of shared housing that includes community spaces like educational and cultural institutions, a collective living room, kitchen and laundry room shared by several apartments. Many of these models are completely cooperative.

“It first developed abroad with the aim of lowering housing prices, but this model also developed a new form of community lifestyle,” Topel says.

In Israel, one can perhaps see this model sprouting in the form of urban kibbutzim.

“In Nof HaGalil, for example, an urban kibbutz rented an eight-story building, and each floor housed an intimate group that maintains a shared bank account,” Topel says. “In a way it’s a kind of small kibbutz, and all eight floors make up one large kibbutz.”

“In order for the cooperative idea to grow and successful,” Shemer explains, “The ideas and values of cooperation need to be embedded in our education. The issue needs to be further explored in academia.”

It is important, she says, that support from the government and the non-profit sector not only include financial assistance, but also training and support for cooperative ventures.

And she maintains that “that the cooperatives themselves need to deepen the bond between each other to help one another.”