“We are constantly recruiting more and more women who want to work, but there is nowhere to go,” said Rena Alturi, 27. Alturi is from Rahat, a large Bedouin town in the Negev, manages the Nazid catering company, which employs mainly women.

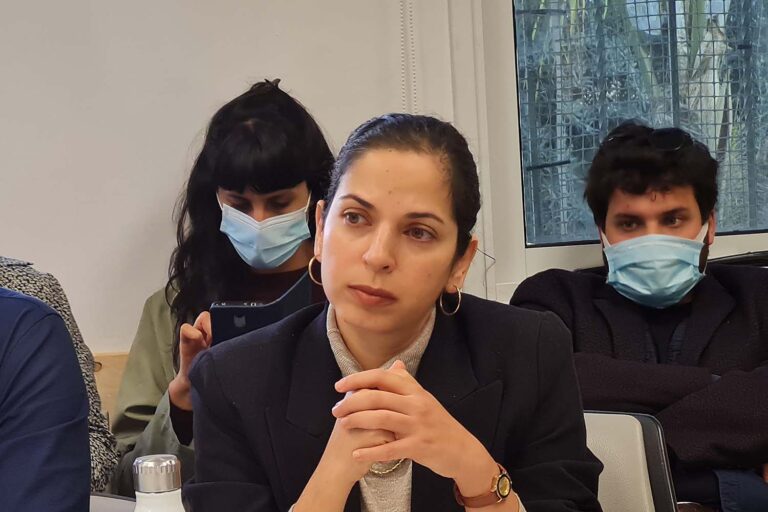

Alturi met with MK Aida Touma-Suleiman, chairwoman of the Committee on the Status of Women and Gender Equality, on their recent tour of Rahat and Lakiya on the subject of employment of Bedouin women in the Negev.

“I would like things related to the progress of women, especially Arab women, to be more in the discourse,” Alturi said. “To work and study, to go out into the world – these are the most important things. I strongly believe that all the women who are currently sitting at home should go out to study and to work.”

First stop: a catering company in Rahat

“Working here gives me a lot,” explained Alturi, who has worked at the company for eight years, since she was 19. “I can be independent and rely only on myself. I started out as a simple employee and today I'm a manager.”

Nazid was established about a decade ago and moved to a factory in the Rahat industrial zone at the end of 2019. It currently employs 170 people, 120 of them women. The factory provides 25,000 food rations a day to children from disadvantaged populations throughout the country.

According to data from the Ministry of the Economy, in September 2021, only 41.4% of Arab Israeli women worked, compared with 81.3% of non-Haredi Jewish women. Among Bedouin women, the most significant barriers are the lack of infrastructure and cultural stigmas, along with a lack of tailored programs to support employment.

“When people are hungry, they’ll eat anything”

“In Rahat, [children] will not eat white rice, so we produce mujaddara and yellow rice. For children in Ashkelon, white rice is produced,” Shai Amira, the factory’s food director, explained.

“But when you’re hungry, you’ll eat anything,” an assembly line worker added, with a laugh laced with sadness.

On the factory visit, MK Touma-Suleiman explained the rationale for the committee's tour.

“We know that the Negev suffers from neglect and discrimination,” she said. ”Whether in the accessibility of jobs, or at the level of infrastructure which prevents people from being able to get to those jobs.”

“We came here to learn what has changed and what else can develop,” Touma-Suleiman continued. “The tour connects three factors: local entrepreneurship trying to provide solutions, women’s organizations and the women themselves, and the authorities.”

Ibrahim Nsasra, a resident of Lakiya, is an entrepreneur as well as chairman and founder of the Tamam Group, which sets up business and social enterprises in Bedouin society in the Negev. He expressed that he would like to see more women from Arab society in high-tech industries.

“The strength and resilience of a state is tested by the most disadvantaged and marginalized groups within it,” Nsasra said.

“The problem is the lack of suitable jobs”

Nsasra recalled a conference on the subject that he attended in 2010, two years after Israel had entered the OECD, when 82% of Arab women in the Negev were unemployed.

”There was talk of employment of women in Arab society in the Negev,” he said. “Smart Jews stood up and talked about it being a cultural problem that wouldn’t let Bedouin women go to work.”

“But even if we look back 20 years, my mother worked, the Bedouin women always worked and labored,” Nsasra went on. “And what I said back then, I still say today: the problem is the lack of suitable jobs.”

Nsasra maintains that the state needs to invest much more in creating paths to employment for women.

“The state pays 25-30% of workers’ wages, it needs to double that, provide incentives, deal with professional training and invest in both the traditional and technological industries,” he said.

But in his eyes, the real investment should be in the education system.

“A child finishes school in the Arab sector without Hebrew, without English and without skills in mathematics,” Nsasra added. “If we want to see the Bedouin community progress, we must take care of the education system.”

“There is no infrastructure to enter the labor market”

Safa Saliman is the deputy director of the Tamar Center, an educational center for young men and women in the Bedouin community. According to her, “Bedouin women want to work.”

”Those who come to our programs are girls, they study science in high school and go on to academia. Among those from Bedouin society in academia, over 80% are women,” she explained.

“But what frameworks do the children have in the afternoon? How many buses leave the villages for the workplace? Women are making progress, but there is no infrastructure to enter the labor market,” Saliman continued.

MK Touma-Suleiman emphasized the state’s role in developing the infrastructure for Bedouin women’s employment, similar to Haredi society.

”When the state decided that it wanted to bring more Haredi women into the labor market, it set up tailored jobs for them,” she argued. ”Today there are entire companies, including high-tech, that employ only Haredi women. I don’t think it should be any different in Arab society. There is human capital, we need to develop jobs that will absorb it.”

Second stop: the Rahat employment center

Nine branches of the Rayan Center, employment centers for the Labor Branch for the Ministry of Economy and Industry, are currently operating in Arab cities. Four are located in the north and five in the south.

”One of the things we’ve done this year is lower the age of participation in the program to 17, enter into schools and work with the principals,” said Gal Ya’akobi, director of population employment at the Labor Branch.

To date, the centers have provided services to about 13,300 participants, of whom 3,302 have been employed. Job seekers from the south come voluntarily to receive assistance in finding work, guidance for professional training, employment programs and courses to improve employment. The center itself employs 110 workers from the Arab community.

The centers usually stand at about 30% placement rates, but most service recipients eventually take unpaid part-time jobs.

Ya’akobi presented the ”Transition Year Program” to the committee, a 9 month program for Arab youth aged 17-24 that provides tools for professional training, combined with subsistence allowances.

“We will also open the program to nonprofits and colleges to expand the program as much as possible,” she explained. ”Currently, most [program] participants are women.”

In the last two years, 6,110 people have applied to the Rayan Center in the southern region, of whom 57% are women. But only 1,323 of them, about 21%, found employment.

”We are trying to incentivize the Rayan Centers in the south with a particularly high monetary incentive, in order to recruit as many women, especially Bedouin women, to choose freely to come to one of the centers for job placement,” Ya’akobi explained.

“We have set ourselves crazy goals in order to locate the unemployed in the Arab community, and reach 20% of them, 9,500 people, by 2024,” she added.

Musa Abu Madigam, director of the Rayan Centre in Rahat, spoke about his own experiences in the Labor Branch’s program receiving the subsistence allowances.

“I was a young man who went through this transition year program along with 70 girls,” he said. “[We were] excited to see our bank account for the first time.”

“We need transportation, employment centers and hospitals”

Musa Elkarini, director of the Rayan Centers in the southern region, added that the most significant challenge is finding jobs.

”We talk about training, but when I go to Kuseife [a Bedouin town in southern Israel] I do not have jobs to place them in, I have to convince the families to let the women go to work in Be’er Sheva,” he explained. “We have thousands of university graduates who are unable to find work, because there is no work.”

“Today there are many women in Rahat with academic degrees who have no employment. There’s manpower, we just need state investment,” added Majid Kamalat, deputy mayor of Rahat.

”Our community faces a very significant challenge,” he said. “In the Bedouin community in the south, 70% [of the population] is under the age of 18. During the pandemic, they couldn’t attend classes on Zoom because there’s a lack of [technological] infrastructure, and so their education went backwards.”

”The time has come for the state to stop caring just about the center, in terms of education, infrastructure and employment,” Kamalat went on. “In the south, we also need transportation, employment centers, communications infrastructure and hospitals.”