The stairwell of the Yemin family home in Sakhnin is decorated entirely with Christmas decorations – a Santa Claus, reindeer, snowflakes and Christmas lights. A’araf Yemin, the priest of the Saint Joseph’s Melkite Catholic Church in the city, is busy preparing for Christmas Mass.

As we entered his house, I asked him what it was like to celebrate Christmas in the Middle East, when there is no snow.

“When the Messiah [Jesus] was born in Bethlehem, it must have snowed,” he says proudly, “it wasn’t invented in Europe.”

The Christian community in Sakhnin is very small: in a city of roughly 32,000 Muslim residents there are about 1,000 congregants at Saint Joseph’s, and another 1,000 in the Greek Orthodox congregation.

“They say we make up ten percent of the city, but it’s closer to five percent,” says Yemin, who the city’s residents call “Abuna,” or “our father,” and who also spent nearly 40 years working at the local school.

“All the [Christian organizations] are named ‘Saint Joseph’ after the Virgin Mary’s husband. In our church, we have the Israeli Scouts youth movement, a women’s group, and also a street named after him,” he explains.

In front of the church, a Muslim family parked their car, and went down with their two children to be photographed next to the decorated Christmas tree. As they got in the car and drove away, Father Yemin says with joy, “Everyone here were my students.”

“One rotten apple can ruin the whole crate”

The festive atmosphere in the community conceals the memory of a difficult event from the previous year: two young people from Sakhnin burned down the Christmas tree in front of Saint Joseph’s, and the Christmas tree in front of the Virgin Mary Church that is currently under construction. Shortly afterwards, the tree near Yemin’s church was burned down again. But according to the priest, these events do not represent the sentiments of the entire community of Sakhnin.

“We live together, with good relations,” says Yemin. “We all share the same home, and the Christians in the city are good and respectable people. I worked for 37 years in the school, there is no one in the city who does not have a good relationship with me. The person who burned the tree is only a child [and doesn’t know any better].”

“As a priest of the community and the emissary of the bishop, the relations between Muslims and Christians in Sakhnin are the most outstanding of any community that I know of,” Yemin continues. “There are good relations, joint participation in festivities and in times of mourning, and daily life as well.

“In every society you find some young people, people that like to get a rise out of others and try to tear down everything that we have built,” Yemin says.

Still, the Christmas tree has been set on fire in Sakhnin twice, and when asked if he is afraid, Yemin answers affirmatively.

“Certainly, I’m afraid. The Christmas tree is accessible in the middle of the road; anyone can do anything to it without anyone’s consent. One rotten apple can ruin the whole crate.”

The young people who set the Christmas tree on fire for the first time have been caught, and their trial is still ongoing. Yemin says that the second arson, as the defendants told the court, is related to a video that went viral online.

According to Yemin, the events did not hurt the neighborly relations between the Christian and Muslim communities in Sakhnin.

“The municipality got involved to help keep the calm, and on the same day we had a party here, and we decorated and lit the Christmas tree again.”

“Two weeks ago, the parents of one of the young men who burned the tree [last year] came here and apologized, and we turned a new page,” Yemin recalled.

“We always remember that we are a minority”

For almost forty years, Yemin worked in the education system in Sakhnin, partly as vice principal and for one year as a high school principal. In a city with a Muslim majority, being a Christian high school principal is not common.

“I never ran into any problems,” he proudly emphasizes.

The education system is shared for both Muslims and Christians in the Sakhnin, meaning that children in the community attend the various and diverse schools in the city. To Yamin’s delight, Christmas has also been observed in the city’s education system in recent years, and everyone is happy to dress in red and white and shout ‘Ho, ho, ho.’

When Yemin retired from the school district in 2009, the bishop of the Catholic community in the Galilee, Elias Shakur, called him and asked him to be responsible for the Catholic schools in the north. After four years, Yemin was appointed to head the Saint Elias Institutions Association in I’bilin, where he works four days a week. The rest of the time, he serves as the priest ‘Economus’ – the highest rank a married priest can reach.

Yemin lives as a minority within a minority: he is a Christian in an Arab society that is predominantly Muslim, within the State of Israel whose majority of residents are Jews.

“I hold all parts of my identity together – Arab, Christian, Israeli citizen, Palestinian,” he says. “There is no one identity before the other, but we always remember that we are a minority.”

“Most of the community goes to mass, entire families”

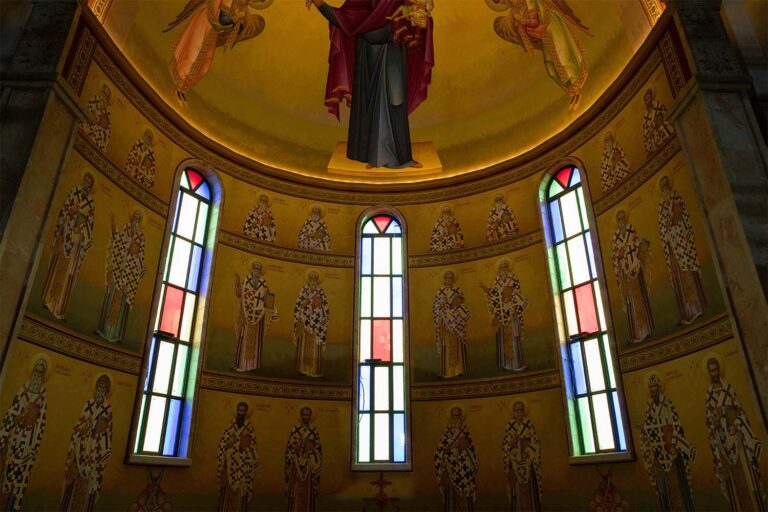

The second church in Sakhnin, of the Orthodox community, has been under construction for over 20 years, since 1999. It is located near Doha Stadium, where the city’s local soccer team plays, with an investment of millions. Its gilded domes are visible at a distance, and the spectacular murals on its ceilings have been commissioned by a Cypriot donor.

The church is not yet open to worshipers, but the large hall and activity rooms at the bottom are bustling with life at this time of year. Last Friday, dozens of children in Santa costumes ran there, in an activity led by the counselors in the Scouts youth movement.

Every Sunday, Yemin holds Mass for members of his congregation at Saint’s Joseph Church.

“Mass begins at 10 a.m., and I arrive before to arrange the benches. Each week, a different family brings offerings to sanctify their dead, and I recount their names in the middle of Mass,” he says.

The choir, which consists of 15 men and women, sings throughout most of the prayer service on Sundays and the rest of the congregation joins in too.

“Most of the congregation come to Mass, entire families, praying, moving one by one to consume the holy wine and bread, the flesh and blood of the Messiah. We conduct festivities and other special occasions downstairs,” describes Yemin.

Yemin continues, saying that at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the congregation began streaming Mass on the church’s Facebook page, with this practice continuing to this day.

Compared to other holy cites, Yemin and members of his congregation decided not to turn their church into a cemetery. In the church there is no commemoration of the dead in special paintings, signs or other religious objects.

“His name is Jesus, it’s important to us”

On Sundays people come to Mass dressed in white, but on Christmas they arrive wearing red. During Mass, they read the New Testament chapter describing the birth of the Messiah, and pay their respects to one another by exchanging gifts. They have a tradition where at the end of the Mass, they hold a bingo game and the Scouts hand out prizes for the winners.

Just before the holiday, Yemin has a request for Israeli Jews.

“Do not say Jesus’ name in vain, it is a profanity,” he says, almost apologizing when asked why he constantly uses the term ‘Messiah’ and not the actual name. “His name is Jesus, it’s important to us.”