“A lot of money was invested in Arab society in the five-year program, but at the same time, [things] went backwards in many ways,” claims economist Dr. Marian Tehawkho, a researcher at the Aharon Institute for Economic Policy at Reichman University in Herzliya. To better understand this contradiction, Tehawkho suggests taking a closer look at what is happening to Arab Israelis in the labor force, especially the young men in the population.

The government’s five-year economic plan for Arab society, known as “Takadum” (“progress” in Arabic), appeared in its first iteration in 2016 as Plan 922 and has led to unprecedented investments in the Arab public in Israel. But in parallel with the implementation of the plan, crime and violence in Arab society has increased, and Jewish-Arab tensions intensified, as could be seen during last May’s Operation Guardian of the Walls.

Many researchers point to the increasing rate of unemployed young people, or young people who are not integrated into the labor force or enrolled in academia, as a possible explanation for the rise in violence in Arab society. Attempting to deal with the phenomenon has become central to any policy proposal dealing with Israel’s Arab sector.

Dr. Tehawkho believes that these young people should be examined in the context of changes in the labor market in Israel, which have a powerful impact on Arab society.

“We are treating this phenomenon as if it were created out of nowhere, but it is important to look at the bigger picture,” she said.

Tehawkho explains that while the government typically takes the approach of asking how young people find employment, she takes the opposite approach, asking “what are the problems and challenges of Arab society, and specifically, [where are] the disparities in the labor market.”

“Economically, when asked how much Arabs integrate into the economy, we look at the employment rate, its quality, and income disparities,” she continued. “Our analysis shows that income disparities are due to gaps in human capital, i.e. the level of education and the quality of education.”

“Arab men are no longer able to integrate into the labor market”

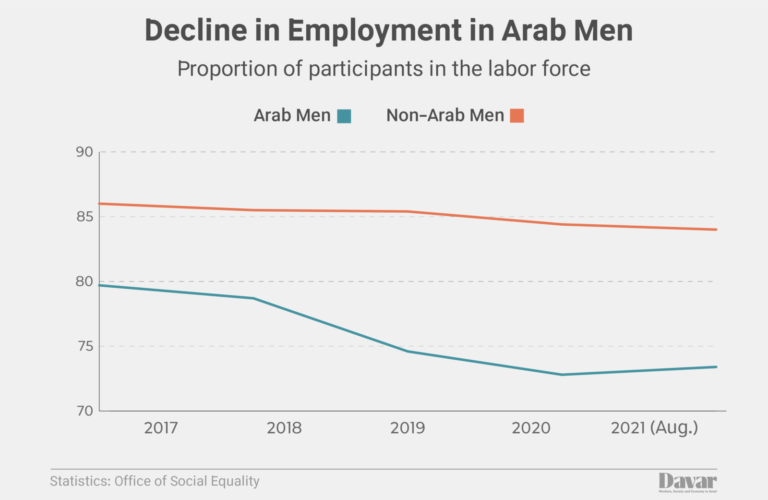

According to Tehawkho’s research, Arab men, in particular young men, are the only population group in which the employment rate decreased in conjunction with the implementation of Plan 922, even before the pandemic.

“The decline in employment among the Arab public was during a period of increased employment among general [Israeli] society. The Israeli economy was trending in a positive direction,” she said.

If in the past, the dialogue centered around the gaps in quality of employment between Jews and Arabs, today there is a new issue, according to Tehawkho. This is the fact that Arab men, specifically uneducated Arab men, are not able to integrate into the labor market at all.

“The level of education did not fall [or] rise, yet the labor market changed,” she explained. “In recent years, the developments in automation and digitization and the demand for high digital literacy have led to an increase in demand for educated workers. The gap created between market demand and the skills and education of young Arab men is widening.”

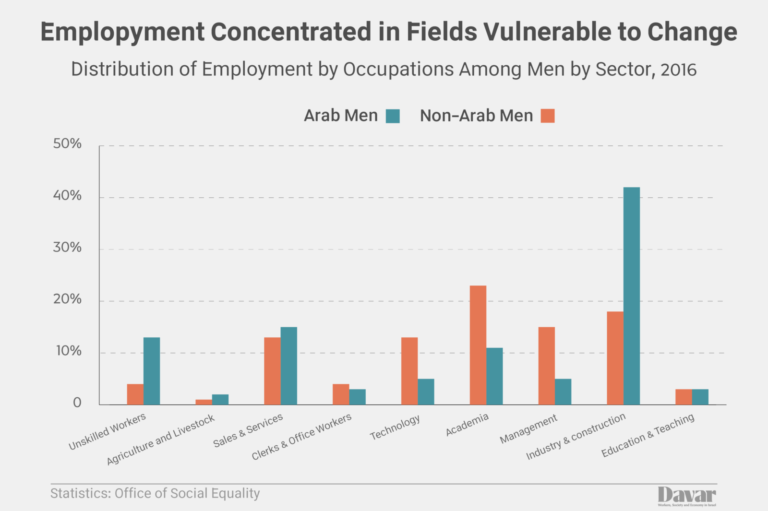

She goes on to explain that this decline in employment is mostly concentrated in the fields of industry and construction. In the manufacturing industry, processes of automation and digitization have essentially eliminated the need for unskilled labor.

“If today, for example, you go to a repair garage, an automated machine is already doing a lot of the repairs, and there is no need for unskilled labor. You don’t need an employee to replace a screw, you need an employee to operate the machine that does it,” Tehawkho said.

“The Jews who were essentially phased out of this field manage to integrate elsewhere, but the Arab men do not succeed. The pandemic further accelerated the transition to automation.”

The construction industry provides employment for between a quarter and a third of all Arab men. While here it is unclear why employment is decreasing, Tehawkho identifies a new phenomenon: an uptick in the proportion of foreign workers, including Palestinian workers from the West Bank. These workers replace Arab-Israeli laborers, despite coming from a similar demographic.

“The goals were not right, and the money did not go to the right places”

The question remains: why have the funds allocated as part of Plan 922 failed to alleviate this declining employment rate? Tehawkho offers her analysis.

“The purpose of 922 was to direct budgets to the underprivileged populations. The plan had no employment targets, and there was no effective examination of where the investments were allocated,” she said.

“Allocating money is not an end in itself. The goals were not right, and the money did not go to the right places, we did not direct the budget to plans that we know work,” she continued.

According to Tehawkho, the new plan “Takadum” is different in that it outlines goals and creates budgets in relation to effectiveness. One goal is the integration of young people into the economy by improving education.

“The Arab education system does not prepare students properly for entering the labor market and higher education,” she said. “Young people currently are under-achieving and lack necessary abilities and skills, like Hebrew and digital literacy.”

Post-high school educational frameworks, such as pre-military programs or “transition years” of professional training could answer this need, but still present some problems.

“So far with ‘transition year’ programs that already exist, they are unable to effectively reach young people with low achievement in the education system, especially boys,” Tehawkho said. “We need to catch them while they are still in the education system, when they are still at the stage of debating what to do with themselves.”

She maintains that there is a need for more information and guidance when it comes to searching for employment, starting in high school.

“For example, a lot of girls in academia study education and teaching. Most will not find a job because the market for teachers is over-saturated, and they will end up in the unemployment cycle,” she said. “We need employment guidance here, which will advise them what to study.”

Older workers, who are already integrated into the workforce, have different needs and therefore, different employment targets set by the 2030 Employment Committee. These targets include direction, skills completion and placement, and must also be addressed as part of “Takadum.”

“A significant part of this is professional training,” Tehawkho said. “We need an organization that knows how to say what the needs are, where the training is and direct these training sessions. There may be overlap with the young people, for example in Hebrew studies.”

“Everyone is in love with hi-tech”

One of the central emphases in the “Takadum” program is entry into the hi-tech industry. Tehawkho says that this is a misplaced effort.

“Arab society has many problems. The difficulty is in prioritizing where to invest each shekel,” she said. “Everyone is in love with hi-tech. To me, it is wrong. Emphasis should be placed on how to help the weaker [populations] integrate more into society and the economy.”

Potential for integration for young Arab Israelis into the hi-tech industry stands at 3%. Meanwhile, 57% of students are not eligible to graduate high school.

“Everyone deals with 3%, and no one deals with 57%,” Tehawkho continues. “Industry and construction do not need them, and then 40% of young people are inactive. This is not surprising.”

Tehawkho points to another problem: the lack of concrete goals for higher education.

“4 million shekels has been allocated for scholarships, that is not enough,” she says. “What is missing is investment in academics and education, and integration in employment.”

According to her, the recommendations of the new five-year-plan are leading in the right direction. But “the question is how to translate them into effective programs.”

No one to see the big picture

Tehawkho warns that despite the cooperation around the program, the lack of coordination between government ministries and the various local organizations may thwart efficient implementation in Arab society.

“It will not work as long as every government ministry develops its [own] plans. The Labor department runs programs, the Minority Sector Economic Development Authority in the Prime Minister’s Office develops its own program and so does the Youth Authority in the Ministry of Social Equality,” she said. “At the same time, there are philanthropic bodies, all of which develop frameworks, but no organization that sees the big picture.”

She explains that the Labor Department appeals mainly to weaker segments of the population and the at-risk youth. On the other hand, volunteer organizations like Ajik work mainly with middle and upper classes, who can integrate into academia and the workforce.

“What about the critical mass, of the 50% that are in the middle?” she asks. “They have no answer.”

“Takadum” defines the issues clearly, but it falls into the complicated network of government agencies, not defining which ministry will implement which part of the program and not demanding synchronization between the agencies once the budgets are allocated.

“My fear is that even in the issue of young people’s frameworks and integration, this is what will happen, because there will be no one body that sees the big picture, has all the information, or knows where it is missing,” Tehawkho said.

“It is not easy to set up such a thing, from the point of view of government ministries. The [internal] bureaucracy can sometimes eliminate plans.”

This article was translated from Hebrew by Zak Newbart.