Israeli taxes are deeply unequal, according to newly released data. The National Tax Revenue Report for the years 2019-2020, released two weeks ago by the Chief Economist of the Finance Ministry, shows that Israel’s tax system brings in less revenue and distributes the tax burden less evenly than other countries.

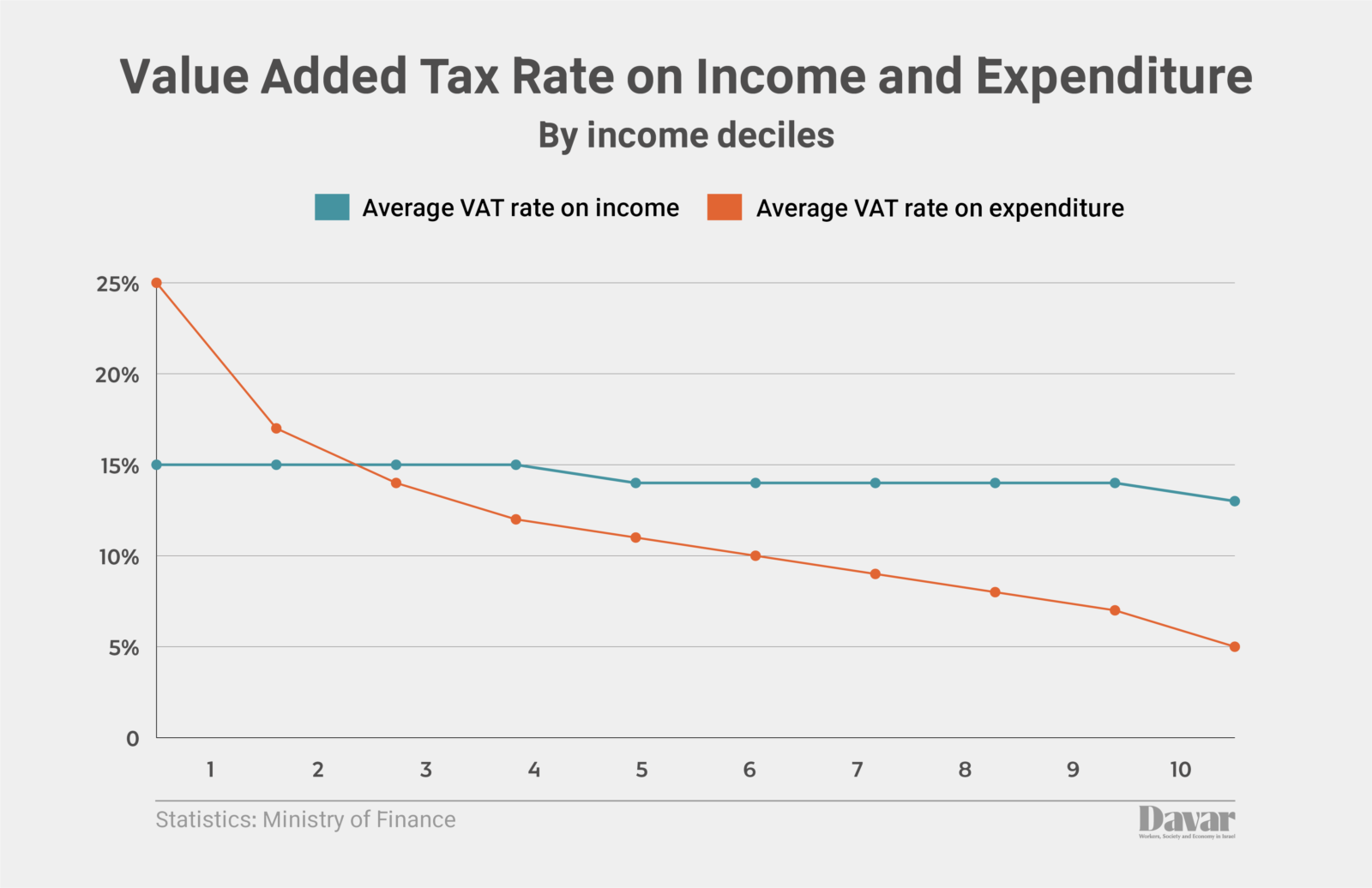

Tax collection is divided into direct taxes, which are collected proportionally based on one’s salary, and indirect taxes, which are collected along with the purchase of certain items. Direct taxes are an example of what economists term a progressive tax, meaning that rate of taxation increases along with the amount of money being taxed, whereas indirect taxes are a regressive tax, meaning those with less money must pay a higher proportion of their income. Subsequently, progressive taxes tend to spread the tax burden more evenly while regressive taxes contribute to socioeconomic inequality.

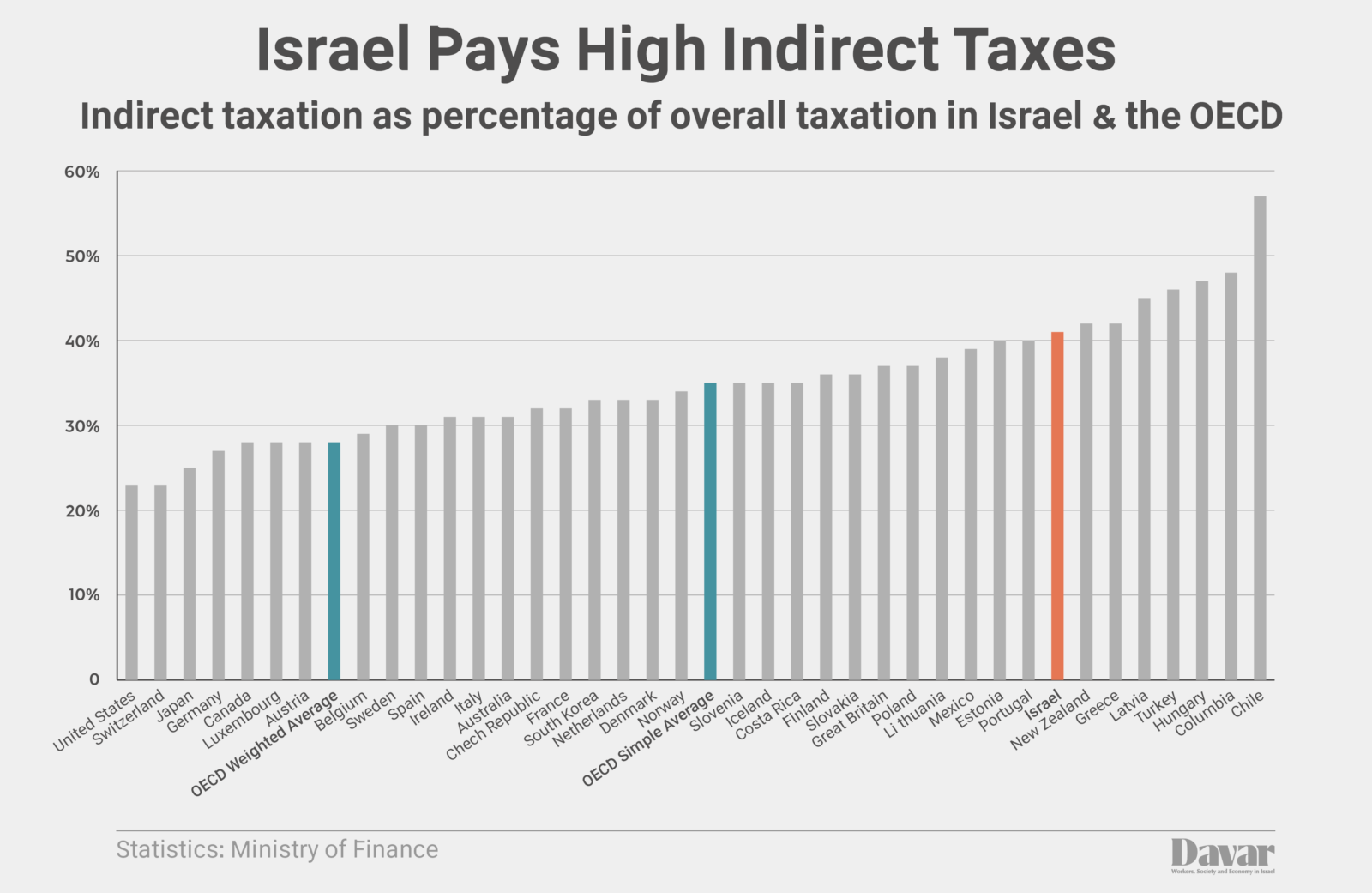

According to the Tax Revenue Report, indirect taxes make up 41% of all taxes collected in Israel, compared to an average of 35% in OECD countries and a weighted OECD average of 28%. Israel’s proportion of tax revenue collected from indirect taxes was one of the highest among developed countries.

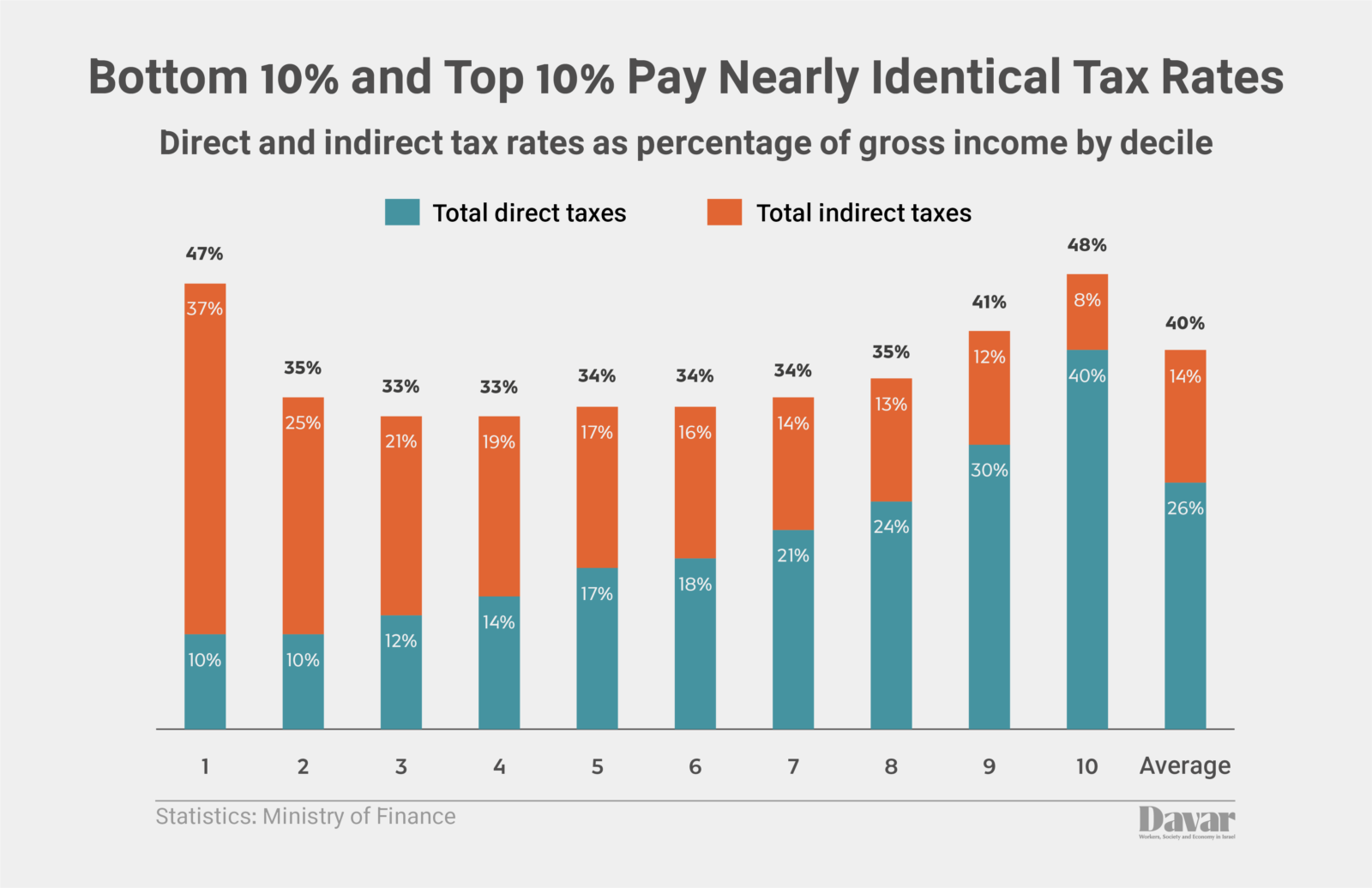

Because of the structure of Israel’s tax system, the effective tax rates of the richest 10% of the population and the poorest 10%, in terms of percentage of gross income, are nearly identical. Members of the bottom decile end up paying 47% of their income in taxes, with 10% of their income going to direct taxes and 37% of their income going to indirect sales taxes. Those in the top decile pay 40% of their income in direct taxes and 8% in indirect taxes for a total of 48%.

The high indirect tax rate experienced by the lowest decile is less extreme for the second and third deciles, which respectively pay 25% and 21% of their income in the form of indirect taxes.

Direct taxes offer some degree of balance to the overall picture. The top decile pays 40% of its income in direct taxes, including 22% in income taxes, 11% in social security payments, and 7% in corporate taxes. For members of the ninth decile, 30% of their income goes to direct taxes, including 13% to income taxes. The lowest deciles do not pay income taxes, but do have social security and health insurance payments deducted from their salaries.

In 2021, nearly half of the Israeli population had an income below the minimum threshold for which income taxes are required. Of those who were ineligible for income taxes, 75% fell in the lowest tax bracket, earning up to 6,290 shekels ($1,927) a month. The remaining 25% did not pay income tax because they received tax credits or other exemptions. The report also revealed a stark gender divide, with 61% of women being ineligible for income taxes compared to 37% of men. This was attributed to women receiving lower salaries and more tax credits.

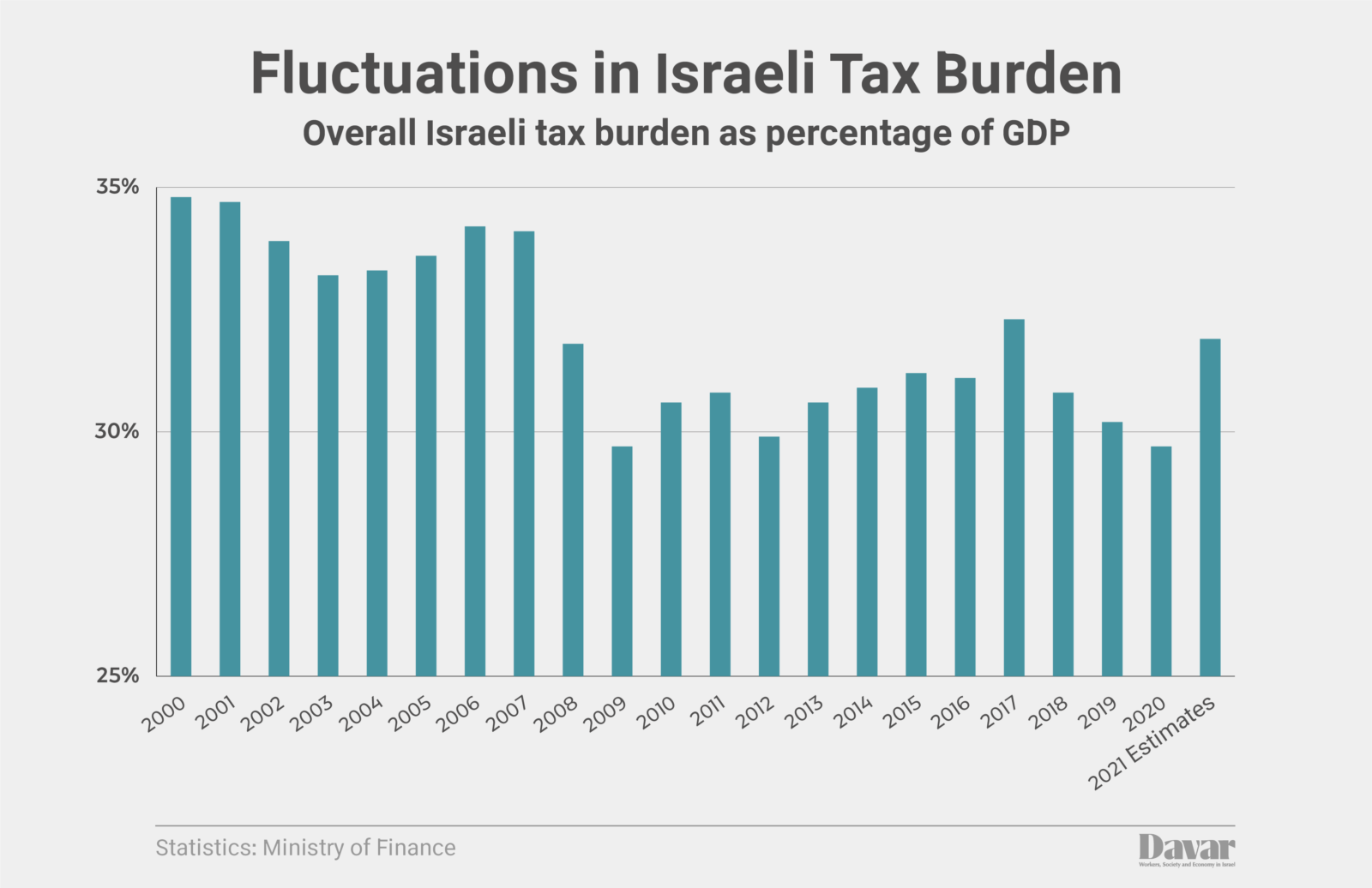

The country’s overall tax burden stands at 29.7% of its GDP, falling below the OECD average of 33.5% and the weighted OECD average of 30.9%, which takes into account the differing sizes of the nations’ economies.

The multi-year average for the Israeli tax burden is down from 35.5% of GDP. The tax burden was lowered sharply in the early 2000s as part of a government program to reduce taxes, but has been more stable in recent years, despite fluctuations created by various tax operations, such as a recent crackdown on shell corporations.

In 2020, at the onset of the pandemic, collection of corporate taxes dropped by 9.9% after 20 years in which it had increased at a yearly rate of 3.3%. Corporate taxes are the government’s third largest source of income, bringing in 38.3 billion shekels ($11.73 billion) in 2020. 91% of corporate taxes were collected from the 21 thousand corporations that make up the top decile of corporations by income.

Taxation accounts for 71% of the cost of gasoline for Israeli consumers. Israel’s excise tax on gasoline is the second highest in the OECD, and its excise tax on diesel fuel is the highest.

The largest tax benefits in Israel are offered for savings and real estate. Pensions and army-financed college funds, which are exempted from taxation, constitute 40% of the total amount offered in tax benefits, coming out to 31 billion shekels ($9.5 billion) a year. Tax benefits as a whole stand at 61 billion shekels ($18.69 billion), making up 5% of Israel’s GDP.

This article was translated from Hebrew by Sam Edelman.