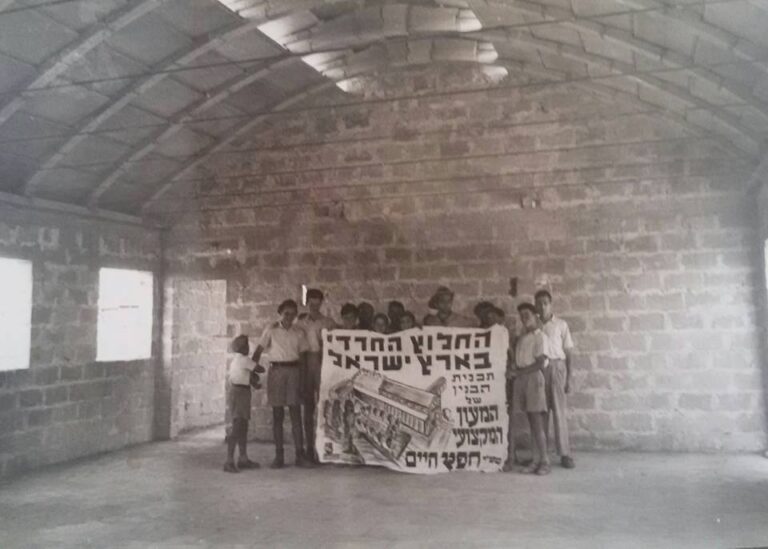

The story of the Haredi kibbutzim is rarely told. Haredi Jews are a group within Orthodox Judaism characterized by strict adherence to Jewish law and traditions, in opposition to modern values and practices. Kibbutzim Mahane Yisrael, Yesodot, Sha'alvim, and Hafetz Haim were all established by ‘Poalei Agudat Yisrael’ (Workers' Association of Israel) — a trade union and Jewish political party from Poland. Their Haredi members worked in the fields, absorbed Jewish immigrants, fought at the borders, and maintained a cooperative lifestyle.

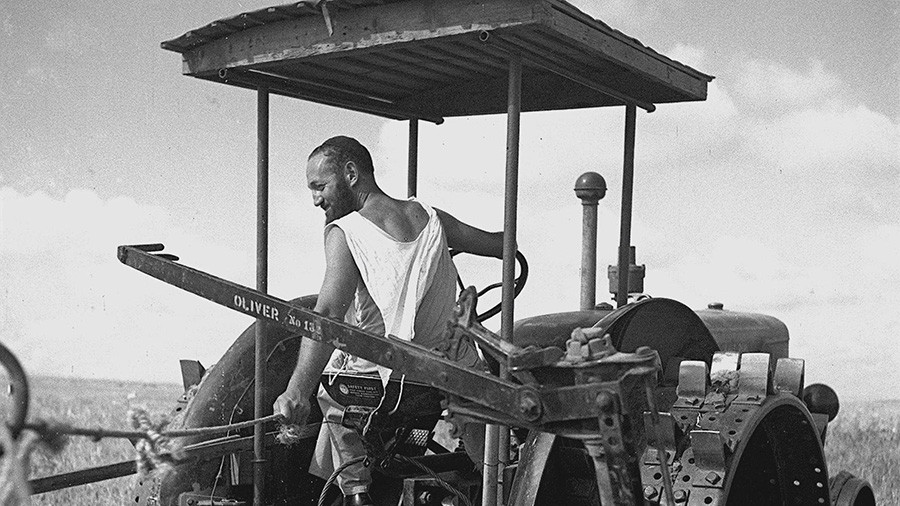

"My grandparents were Haredi, and they were also kibbutznikim," said historian Dr. Noa Rosen, whose doctoral thesis investigated the development of Haredi kibbutzim. “On one hand, they strictly observed the halachot (Jewish laws and traditions), and on the other, they drove a tractor and plowed fields. People are always surprised to hear that."

"The character of the kibbutz today more closely resembles ‘national-religious’,” a term used to refer to Israelis that advocate observing Jewish ritual, along with integration into Israeli society, and a positive attitude towards Zionism, said kibbutz member Karen Hamiel. "The founders of the kibbutz immigrated from Germany. They didn't look like the Haredim in Bnei Brak, but they were Haredim, they called themselves Haredim, and one of the expressions of that was being anti-Zionist."

If they were anti-Zionist, this begs the question – why would they establish a kibbutz?

"At the time, the meaning of anti-Zionist was not an opposition to immigrating to Israel, but rather opposition to the Zionist movement, which was trying to turn Jews into ‘the new Jew’ — strong, self-reliant, and physically active,” Hamiel said. “Our grandfathers wanted to preserve the old Jew, with the beard, the kippah, the peot (sidelocks), the study of Torah and the mitzvot."

The founders of the Haredi kibbutz immigrated from Germany as part of the Haredi socialist movement Poalei Agudat Israel.

"They rebelled against the Haredi rabbis of their time by engaging with the Zionist movement," Rosen said. "Agudat Israel was against Zionism, and even in Israel they were not treated warmly by the Zionist institutions because [the Zionists] did not know what to make of them. They called themselves the people of the 'Third Yishuv', because they did not identify with the old urban Yishuv that lived on commerce and halukka (charity funds for Jewish residents of the Land of Israel), and on the other hand, they did not identify with the New Yishuv which, as far as they were concerned, did not observe Torah."

The story of the Haredi pioneers is not often told, despite their contribution.

"They were a minority group within a minority, both among the Haredim and among the kibbutznikim,” Rosen explained. “Haredi men who work are a minority of the Haredi minority, let alone Haredi farmers who drive tractors and plow fields. For this reason, this movement is not widely studied or well known."

Karl Marx alongside Moses

The Haredi kibbutz is not a movement in and of itself, but rather a part of the Poalei Agudat Israel, a minority of whose people immigrated to Israel before and after the Holocaust. Although the movement was not necessarily Zionist, after the establishment of the state of Israel it was recognized as a “settlement movement”, and today fourteen communities belong to it, including nine moshavim and two kibbutzim. Of the four Haredi kibbutzim established by the movement, Kibbutz Mahane Israel, near Dovrat in the Jezreel Valley, was dismantled and abandoned, and Kibbutz Yesodot became a cooperative moshav. In this way, today only two Haredi kibbutzim remain, Sha'alvim, in the Gezer regional council, and Hafetz Haim, near Gedera. Both joined the Kibbutz Movement and were later privatized.

Hamiel emphasizes that the movement’s goal is to support Haredi workers, not married Yeshiva students, in contrast to most Haredi communities today.

"To this day, Kibbutz Hafetz Haim is committed to this concept and also the principles of the Zionist movement. Army enlistment is mandatory for every man who wants to be accepted as a kibbutz member; the same goes for two years of national service for women,” she says. “There are no exceptions made about this. And this is one of the reasons why over the years [Poalei Agudat Israel] has moved closer to the ‘knitted kippa’ movement (a nickname for national-religious) rather than the Haredim in Bnei Brak."

Rosen says that members of the movement spoke in favor of socialism and denigrated capitalism in the same words used by Karl Marx, and saw this as a part of Moses’ religion. One of the founding letters of the association reads: "The Torah has never made an alliance with the exploiters. The Union of Poalei Agudat Israel demands from the respected Torah scholars amongst our people that they will protect zealously the socialist fury of the Torah and in the name of the Torah speak loudly and publicly against the greed of capitalism."

The movement's kibbutzim in Israel joined the Union of Kibbutzim, a secular movement that was connected to Mapai (a predecessor of the modern Israeli Labor Party) and not to the Religious Kibbutz Movement. Rosen sees this as self-evident. Her mother’s grandparents are founders of Hafetz Haim and her father's side are founders of the national-religious kibbutz Lavi.

"The religious kibbutz of 'Hapoel HaMizrachi’ (a political party and settlement movement representing religious Zionism) was a red flag for them," Rosen said.

One of the interviewees in Rosen's research, a member of Hafetz Haim, told her: "When we would visit my grandparents at Kvutzat Yavne (a national-religious kibbutz), my mother would say that even the water there is not kosher. You must not eat or drink there, because the dishwasher in the dining room is not separated for dairy and meat. They didn't want us to visit our aunt in Yavne so that we wouldn't be corrupted. She had no problem with us visiting Givat Brenner (a secular Socialist kibbutz), for example."

The interviewee explained that their parents would argue on the subject, but in good spirits.

"Father would tell Mother that Hafetz Haim is not a real kibbutz, because they decided that the reparations from Germany would be transferred to the members and not to the kibbutz. Mother would say that the national-religious kibbutz does not observe mitzvot properly because they do not set aside donations and tithes, and do not make sure to keep a shmita (Jewish law which mandates that seventh-year land is left to lie fallow and forbids all agricultural activity)."

The year of shmita was the primary bone of contention between the national-religious kibbutzim and Haredi kibbutzim.

"The national-religious kibbutzim of ‘HaMizrachi’ were based on the permission to sell land based on Rav Kook's ruling, a ruling not accepted by the Haredi rabbis still living in Eastern Europe,” Rosen explained. “Kibbutz Mahane Yisrael, for example, made a living purely from tilling the land, and the shmita year threatened their livelihood."

Mahane Yisrael was founded in 1925 in the Jezreel Valley and was the first Haredi kibbutz. It fell apart twice in the first decade, but the lands remained in the possession of Poalei Agudat Yisrael, so it was settled a third time in the mid-1930s. When the establishment of the kibbutz began, for the first time, its members had to deal with the shmita year of 5698 of the Hebrew calendar (1937-1938).

"Even so, they lived in poverty," Rosen said. "The Zionist institutions did not help, and their community in Europe hardly helped either, because it required contact with the Zionist institutions. So Haim Shenor, the treasurer of the kibbutz, addressed the rabbis and asked them for permission to work the land in the shmita year. After the rabbis flatly refused, Shenor addressed Rabbi Avraham Yeshaya Karelitz (the Chazon Ish), who was close to the members of the movement, and a sort of spiritual authority for them.

"He explained to him that without growing produce they would not be able to buy food and would starve. Rabbi Karlitz replied that any kind of agricultural work during the shmita year is like eating chicken in butter (an act prohibited by Jewish dietary law). Adherence to the prohibition led to the dissolution of the kibbutz for the third and last time. Until then, it was the only kibbutz of Poalei Agudat Yisrael, until the establishment of Kibbutz Hafetz Haim.”

Hafetz Haim was founded by married Yeshiva students who wished to establish “a local creation in memory of Rabbi Hafetz Haim.”

"In 1933, they went to Rehovot with the aim of renting land and working it," Hamiel said. "They probably seemed strange to the local farmers, who were in no hurry to entrust their land to them. In those days, there were Haredi farmers in the moshavot (private farming communities) as well, but they operated according to Rabbi Kook's permits, which Poaeli Agudat Israel did not accept. In the end, they found someone who agreed to lease them the land near Gedera."

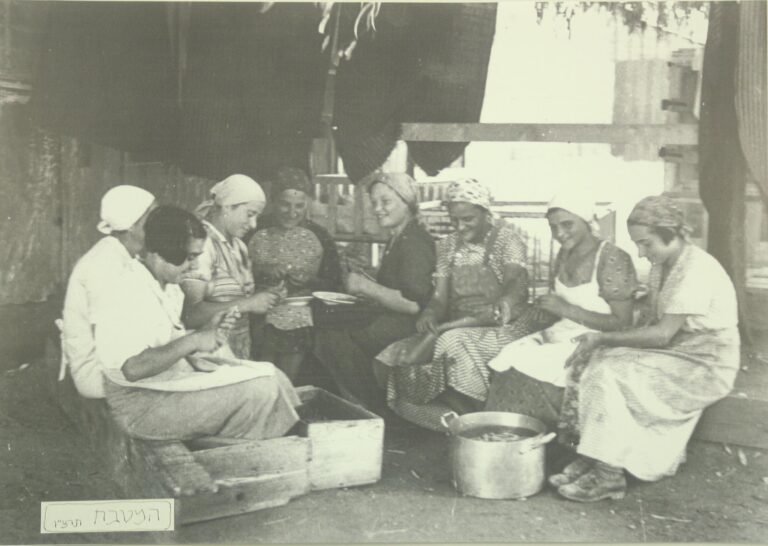

Hamiel, who researched the kibbutz’s history, says that in the beginning only men were allowed to reside on the land they worked.

"After one couple got married, it was decided to accept women into the group as well," she said.

In 1936, they realized that in two years the year of the shmita would arrive. They spoke with the Council of Torah Elders for consultation. The council had no solution, and it passed the question to Rabbi Chaim Ozer of Vilna, who also did not know how to answer.

"We’re talking about very smart people, but for 2,000 years no one dealt with the mitzvot related to the land of Israel itself," Hamiel explained. In the end, they appealed to Rabbi Karlitz, who would go on to help them find a solution.

Chief Rabbi Yitzhak Isaac Halevi Herzog (grandfather of the current president of Israel) invented one of the proposed solutions. He developed, together with Karlitz, the “shmita plow”, which moves the soil a little and creates a false representation as if it is cultivated, but not in a way that can be sown.

"This was a time when those who didn't plow their land lost it," Hamiel said. "They didn't make bread with this, but at least they could keep the land. To this day, we are careful about this matter — if you had come here in the last year, you would have seen that all our land is fallow."

To get through the shmita year without starving, Rabbi Hauser organized a donation that helped the kibbutz members purchase their first cows.

"Despite fundraising, they reached the brink of hunger, and families who had children left the kibbutz," Hamiel explained. "In the same year, Mahane Israel also disbanded. It's not as if the Jewish masses opened their wallets for them. But the donation of cows later led to the invention of the ‘Shabbat observant automatic milking’ — more on that later.”

After the first shmita year, another Haredi group of immigrants from Germany settled to work the land in Kfar Saba. The groups made contact and decided to unite as soon as one of them found land for settlement. In 1940-1944, the groups went through difficult years. The war in Europe caused them to lose contact with the great Torah scholars of their generation, and in the end, it turned out that most of them perished in the Holocaust. Life in Israel without any support from Europe and the Zionist institutions was burdensome and bitter.

Meanwhile, David Ben-Gurion began pressuring them to join the Zionist movement.

"His interest was clear — he wanted to gain recognition from the British that he is a representative of all the Jewish people and not just of the labor movement," said Hamiel. "His researchers describe it in [Ben-Gurion’s] own words: from a class to a people. Therefore he offered them work, land, and weapons if they would only pay the price and join the Zionist movement."

Hamiel claims that only when they arrived at the point of ending the kibbutz or joining the Zionist movement, the members of Hafetz Haim agreed to join the movement. It happened in 1944, during the war when they did not yet know what happened to their brothers in Europe.

"The Chazon Ish gave them reluctant approval to join the Zionist movement. With their inclusion in the Zionist institutions, they received the lands of Kfar Szold near Gedera, after Kibbutz Kfar Szold gave up and moved north, and Kibbutz Hafetz Haim has been located there ever since. The Zionist movement saved them, and perhaps one of the reasons for the Chazon Ish's agreement is the bitter fate of Kibbutz Mahane Yisrael. In any case, this was the first time that a Haredi group joined the Zionist movement."

The origin of robotic milking and hydroponic farming

"From the moment Kibbutz Hafetz Haim joined the Zionist movement, their contribution to the establishment of the state was enormous, and unfortunately, due to modesty, it is not recognized," said Rosen. "That's why Shai Reichner, head of the Nahal Sorek regional council, is investing in the establishment of the ‘Haredi Pioneer' (HeHalutz HaHaredi) museum, which will commemorate the work of the founders of the kibbutz in various sectors of the establishment of the state."

The members of Hafetz Haim’s contribution began with the absorption of refugees of the Holocaust.

"Because of their diasporic appearance, the beards, the Haredi clothing, it was most effective to mix the illegal immigrants arriving in Israel among them,” Hamiel explained. “The members of Hafetz Haim happily agreed to this — they would receive news every night about the point where a smuggling ship would dock, go to the beach, and rush to mingle with the immigrants and bring them to the kibbutz."

The great advantage of bringing immigrants to Israel through a Haredi kibbutz was that it reminded the immigrants of home, as opposed to the rest of the labor settlements that were foreign to them.

"Many of the refugees of the Holocaust were afraid to immigrate to Israel because they feared the lifestyles practised there such as the secularism and the clothing. They felt at home at Hafetz Haim,” Hamiel said. “They realized at Mossad LeAliyah Bet (a branch of the Haganah that facilitate Jewish immigration to British Palestine) that it was of great significance to send the members of Hafetz Haim to camps in Europe because they have the ability to deal with problems that the secular kibbutznikim simply did not understand."

Yosef Bacharach, one of the first rabbis of Hafetz Haim, was a rabbi as well as a scientist.

“His life goal was to use modern science to enable the establishment of the Land of the Torah in Hafetz Chaim," Hamiel explained. "He worked day and night on solutions to problems that arose in the fields of agriculture and halacha."

One of the remaining famous stories is about the development of kosher automatic milking. In 1946, due to increasing tensions between Arabs and Jews, it became too dangerous to allow Arabs into the Jewish settlements, which led to the end of milking on Shabbat by non-Jews. Other communities found non-kosher ways to get by, but for Hafetz Haim it was a complex halachic issue. On the one hand, the prohibition on animal cruelty requires milking the cows to prevent a buildup of milk in the udders causing suffering. On the other hand, there is an absolute prohibition on milking on Shabbat.

"Rabbi Bacharach heard about a robotic milking machine abandoned in the streets," said Hamiel. "This is the first machine that arrived in Israel from Sweden to one of the kibbutzim, and in that kibbutz, they could not make it work and claimed that it harmed the cows. Rabbi Bacharach took the machine and ordered an engineer from the Swedish manufacturer, who, together with the Chazon Ish, installed it so that it could milk on Shabbat. It was kosher certified and worked excellently, and following the success, additional milking machines were ordered, also in secular settlements."

Bacharach was killed in the War of Independence. He was a combat medic and accompanied one of the convoys bombarded on the way to Jerusalem.

"It was a great loss. He was a rabbi and an important scientist in the kibbutz, along with kibbutz rabbis Rabbi Hillel Bruckenthal and Rabbi Kalman Kahana, who convinced Ben-Gurion not to sign the Declaration of Independence on Shabbat," said Hamiel.

Rabbi Bacharach's legacy, using science to renew kosher Hebrew agriculture, continued in Hafetz Haim.

Meir Schwartz, a Holocaust survivor who was one of the founders of Hafetz Haim and who died last year, began conducting experiments in the late 1940s in growing agricultural produce without soil. According to him, he got the idea to grow vegetables in concrete beds filled with gravel from his friend Binyamin Mintz (later Minister of Postal Services and Deputy Speaker of the Knesset).

“He conducted the experiments in the afternoon, outside of working hours, because the kibbutz members did not believe that anything would come of it. He wrote in his memoirs that there were those that ignored his experiments, which was insulting. Some were angry with him, mocked him, and claimed that he gave the kibbutz a bad name as filled with idiots because it is obvious that plants cannot grow without soil,” Rosen said.

"There were only two friends who supported him. One of them was my grandfather,” Rosen went on.

In the shmita year 5712 (1951-1952), Schwartz was already able to grow vegetables without soil, in a method that was then known only to a few, called hydroponics. Via experiments he conducted, he specified the different variables required to grow plants in gravel, refined the chemicals that must be added to the water and developed methods that, in the future, would be used all over the world.

"The success of hydroponic agriculture in Hafetz Haim led to an increased interest in the method," said Rosen. "Ben Gurion wrote to him that the method might help settlers in the arid Negev. Later, he opened a research institute and advised governments all across the world. Even NASA invited him to teach them about hydroponics to test the potential of growing vegetables in space. He became a known name around the world and served as president of The International Society for Soilless Culture and as president of The International Society of Religious Researchers. All these are thanks to the observation of the shmita.”

Kibbutz rules and modesty rules

Over the years, Kibbutz Hafetz Haim has become a significant tourist hotspot for the Haredi sector. Every year, hundreds of thousands of tourists visit the only water park in Israel that is completely separated between boys and girls, at the hotel that holds ‘Badatz’ kosher certification (a strictly orthodox kashrut certification), which does not have a TV in the rooms, and each room has its own separate sukkah.

"As children, we used to work in the tourism industry," Hamiel recalled. "If it wasn’t enough to wash all the dishes in the kibbutz dining room, then you could always wash more dishes at the hotel."

The kibbutz developed unique traditions.

"In terms of clothing, there are modesty regulations added to the kibbutz regulations, but it's not black Haredi clothing. It's not like in moshav Yesodot, where you end a day's work on the tractor, shower, and then change into Haredi clothing. For us, it's clothing more reminiscent of the national religious garb," she said.

The kibbutz's laundry also operated a little differently from other kibbutzim.

"Among the Haredim, it is forbidden to assign numbers to people," explained Hamiel. "I think this was greatly intensified in the Holocaust. That's why we don't have numbers on the clothes. Instead, we simply embroider the name of the person to whom the clothes belong."

Another characteristic that is unique to the Haredi kibbutz, and related in Hamiel's opinion to the burden borne by Holocaust survivors, is the large number of children.

"I am the eighth of ten children, which is really not unusual here. The feeling is that there was compensation here for everything that was lost in the Holocaust."

Hafetz Haim was one of the first kibbutzim to discontinue communal child-rearing and Friday night dinners in the dining hall. In contrast to the national-religious kibbutz, most of whose kibbutzim remain cooperative to this day, the Haredi kibbutzim were already privatized two decades ago. Hamiel relates this to the communal-Haredi nature of the kibbutz, which was privatized in 2000 and has since operated in a collaborative model of 'the renewed kibbutz'.

This article was translated from Hebrew by Jonathan Epstein.