The new neighborhood in Kibbutz Kfar Aza overlooks the heart of Gaza City, less than five kilometers from the settlement fence, with the perimeter fence standing. In times of war, this distance translates to less than 15 seconds notice to find a shelter. "These are the Wallerstein housing units," points out Shai Harmesh, former head of the Shaar HaNegev Regional Council (a council responsible over the populations of the northwestern portion of the Negev). "Without Wallerstein, these units could not have been built."

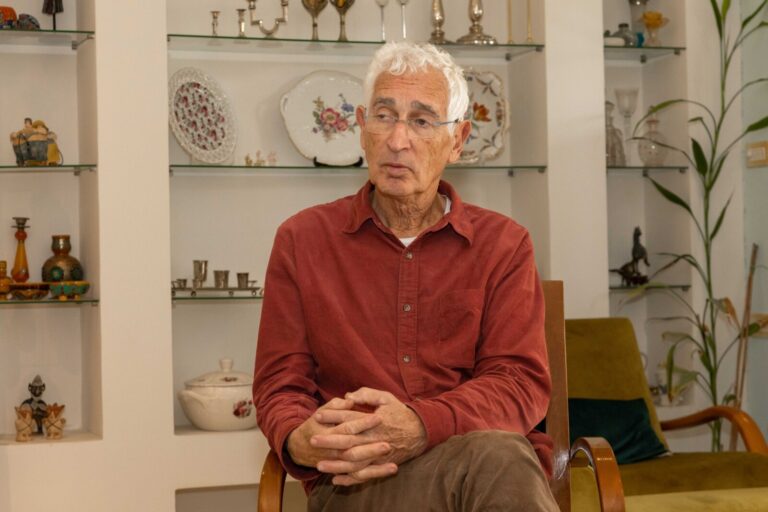

Pinchas Wallerstein (74) is the former head of the Yesha Council (an organization of municipal councils of Jewish settlements in the West Bank) and head of the Binyamin Regional Council in the West Bank, currently living in the settlement Ofra. He first arrived in Shaar HaNegev on behalf of the Negev and Galilee Ministry after 2014 Operation Protective Edge, while the kibbutzim in the area were in demographic collapse. Until then, Wallerstein knew the area mainly from the other side of the fence, as a leader in the 2005 struggle against the disengagement from the Jewish settlements of Gush Katif in Gaza.

Wallerstein was one of the first settlers in Samaria and a student of Hanan Porat, a right-wing Orthodox rabbi who sat in the Knesset for several years throughout the 80s and 90s. Despite this, Wallerstein insisted on speaking to Davar about the current rifts in Israeli society in Kibbutz Kfar Aza, where 80 percent of the votes in the last elections went to center-left parties.

Along with Harmesh, a member of the Kibbutz Movement and a former member of the Knesset on behalf of Kadima, Oshrit Sabag (48), coordinator of demographic growth in the nearby Kibbutz Nahal Oz, also attended. When they both heard that Wallerstein was interested, they signed up without asking for more details.

Many compare the struggle for judicial reform, this period, to the period around the disengagement from Gaza in 2005. Do you see a similarity in terms of the intensity of the public debate?

Sabag: "No. The intensity is greater today."

Wallerstein: "I do, it definitely reminds me of the disengagement."

So it's a matter of point of view?

Wallerstein: "For sure. It reminds me of the days of disengagement, mainly in terms of the split in the nation. When I saw the recent demonstrations, it was clear to me that they were not really about legal reform. It's a fight for identity. The demographic changes and the current coalition scare those who feel they will no longer have the right to be 'free in their country', free in the sense of secular. People with whom I have had conversations for many years call me with real anxiety about the identity and character of the State of Israel. I understand that, a government made up of Agudat Israel, Shas, Smotrich and Ben Gvir – even to me it’s a little scary, so it's clear to me that the liberal public is even more afraid."

Another common question is that of the limits of the struggle.

Wallerstein: "Pushing the limits today is causing great anger on the right. What does my wife say? The media is not activated, it is activating. They resorted to wild measures from moment to moment, blocking roads. When I blocked a road during the days of disengagement, they immediately handcuffed me and took my fingerprints.

"I want the protesting public to define the boundaries of their protesting. Where is the red line that will not be crossed? The discussion about the army, about volunteerism and reserves, it makes no sense for me to tell them anything about it. But I expect them to [respect them], as we did back then in Kfar Maimon.

"I'm also not sure that the demonstrations are now under control and that there is someone who can say: 'Please evacuate now because this is what has been decided.' Once decided, the struggle turns from changing the decision to cementing it."

"The Haredim have an advantage. We had disagreements, but also a clear leadership"

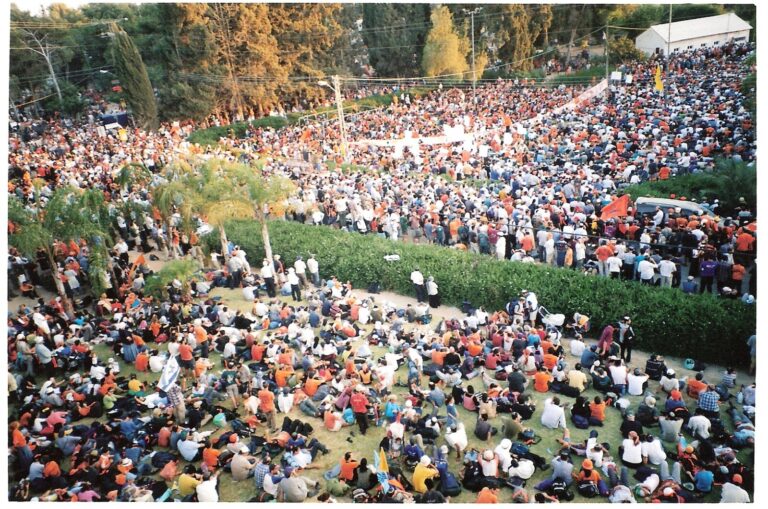

Wallerstein, as one of the leaders of the struggle against the disengagement plan, led a moderate line, which culminated in the dispersal of the protests in Kfar Maimon. In July 2005, thousands of protesters and activists gathered in Kfar Maimon near Netivot, with the intention of breaking through the fences and continuing to the settlements of Gush Katif, in order to make the evacuation more difficult. A group of rabbis and activists at the headquarters of the struggle, including Wallerstein, prevented the event, which could have ended in a sharp confrontation with the security forces and the police. For this, Wallerstein paid a price: in 2008 he was forced to resign from the position of head of the Yesha Council.

"The anger towards me continues to this day, and you can see it in the comments on my Facebook,” he said. “It was a difficult dilemma whether to continue, there could have been an uncontrollable confrontation. One of the rabbis told us angrily: 'Of course I would not raise a hand against a soldier. But I wanted blood for blood after that soldier hit me.' I told him I wasn't prepared for that to happen."

Today it is not always clear who is leading the protest. Was it clear to you?

"The Haredim have an advantage. We had big disagreements among ourselves, but also a clear leadership."

Were you in control all the time?

"We were in control, but it was at the cost of yelling, crying, and anger. We had to deal with tensions within the community. In a religious system, there is also a hierarchy. The head of the Yeshiva at Merkaz HaRav at the time was the old Rabbi Shapira (Rabbi Avraham Elkana Kahana Shapira). Even before Kfar Maimon, there was a phase where they scattered ‘Ninjas’, (bent nails), and oil on roads. We went to the rabbi of the leaders of the struggle and told him: 'This is forbidden. It endangers human life.' There were several rabbis sitting there, he looked at one of them and said: 'Did you hear? This will not happen again.' And it really didn't happen again."

What is your personal position regarding the judicial reforms?

"I don't like the prosecutor's office and the court, but I have priorities. As soon as there is a final decision by the court, I respect it. I would like all the proposed changes and I am ready to give up most of them. Political unity is more important. Rabbi Druckman used to say: ‘Little by little'. What is agreed upon now is less than we would like, but for me, what is agreed upon is better than anything else – to start. This is religious Zionism."

This is not the position of the religious Zionist party.

Wallerstein: "We, the leaders of Gush Katif, planned to issue a joint statement in this spirit. If the Prime Minister had not announced that he was stopping for talks, we would have published it."

Sabag: "It could have had a great meaning. What is jarring for people is the charging forward. You yourself say, a government that contains extremist elements and does not contain a broad consensus of the people is unstable. Perhaps this is also true for the previous government. We have reached a situation where the centrist blocs cannot sit together. So we get into situations that displease a significant portion of the public."

Wallerstein: "It's clear to me that for Lapid, the goal is to topple the government, and for Gantz, the goal is to solve the problem. That's why the polls turn in Gantz's direction. It's not just Gantz himself, it's his entire attitude.

"On the right, the bigger problem is the need to take revenge. People tell me: 'You screwed us with your compromises in Kfar Maimon, we will not forget or forgive, and now it's time to make up for what we lost.' Homes were destroyed and people were sent to live in trailers. It took years until they moved to permanent homes. And the joy on the sidelines; you'll probably find pictures of people standing with signs against the evacuees right when they were being evicted.

"It's a question of whether you're ready to get out of your bubble and try to see the other person, and it doesn't matter if he's ultra-Orthodox or a distinct leftist. You need to understand what bothers him, what's important to him, how he lives."

Didn't the disengagement from Gaza discourage you from the thought of unity?

"In the end, I experienced the story of disengagement as something that requires entering into a religious perspective. What is my relationship to the State of Israel, which was established by secular people? What is my religious relationship to them? Once you reach a decision on this issue, it is no longer a dilemma. It dictates the nature of your life. That's why I also felt a mission to come here, to the settlements surrounding the Gaza strip. I don't care who the people here vote for, I see them as pioneers. As Trumpeldor said: Where the plow passes, there the border passes. We are now two kilometers from the border.

"For me, my arrival here was really a departure from my bubble. Here, in Kfar Aza or Nahal Oz, a rocket alert is a waste of time. Theoretically you have 15 seconds, but in the end, not even that. I remember one evening when I was in Ofra, they announced a rocket alert, and then they announced that it was a false alarm. I called a friend in Nahal Oz and told her: 'How lucky it was a false alarm.' She answers me: 'You fool, don't you understand that with this alarm I must choose which of my children to grab?'. Then I began to understand what it means to choose to serve these people. To be connected with them in heart and soul."

"There is an absolute connection between community resilience and demographic growth"

During Operation Protective Edge, in 2014, when Wallerstein arrived in the area, the Israeli settlements surrounding Gaza were suffering from a severe social and demographic crisis. Beyond the mortar and rocket fire, the exposure of the attack tunnels dug by Hamas under the settlements undermined the basic security of living in the area.

"We collapsed within a month,” Sabag explained about Nahal Oz. “Out of an education system of 80 children from the age of zero to 12, we were left with about 40. Each settlement had one terror tunnel – here, they found five. Several times we received text messages: 'Stay at home and close the doors', each time for a few hours. It was nerve wracking even if you're not in the settlement, and it happened at least five times during Operation Protective Edge.

“At least they proved I wasn’t crazy," she added with a half smile. "I said that every night I could hear motorcycles, and a tunnel with motorcycles was indeed found."

In the nine years that have passed since Operation Protective Edge, Nahal Oz, bordering the perimeter fence, not only recovered, but even tripled in size. The three testify that in most of the surrounding settlements the situation is similar.

Why do people come here?

Wallerstein: "When I came here, I knew there was an absolute connection between community resilience and demographic growth. I said: 'Stop marketing. Rally people around the flag and they will come.' They improve housing, but they also know that they are closer to the border. Therefore, to be in the company of such people and in their community is a privilege."

Harmesh: "I don't think people here speak Zionism. People come here because they are tired of meeting their neighbors only when they take out the trash. People are looking for community. And the kibbutz knows how to provide that."

Sabag: "That's a very good question. Before I started marketing, I researched it – what brings people to such crazy places? What Shai said is the number one parameter: community. I interviewed a lot of families who also spoke on a strong Zionist ideological element. The economic aspect is also a consideration.”

“Society houses" is a method to develop land and build housing within the kibbutz by the cooperative, sell the apartment to the new resident and use the money to build the next house. How did this idea come to Shaar HaNegev?

Wallerstein: "Starting in the 1980s, except for the purpose of absorbing the immigrants from the Soviet Union, the state greatly reduced government construction. This method was the method by which we built in Judea and Samaria."

Harmesh: "Wallerstein is the one who promoted this idea of society houses before the government ministries. In September 2014, the day after the ceasefire, he came here for a meeting with the director general of the Prime Minister's Office at the time, Harel Locker. We had to convince them to recognize the difference between the settlements of the front line, adjacent to the fence, those that absorbed the strongest orders of magnitude of the fire during the operation, and the other settlements. Locker then opposed our demand for assistance of a billion and a half shekels for the construction of 250 society houses. He told us: 'Who will come to live here?' He claimed that the houses will remain empty. I told him: 'If you don't build, they won't live here anymore anyway.'"

Harmesh: "Wallerstein has a golden share here. In the midst of the greatest crisis, he came with the knowledge and abilities of the settlers, which we have lost since the great crisis of the Kibbutz Movement. His rights here have no end or limit, because he was the one who made the expansion possible.

“What happened here is a miracle. Despite everything, there has been astonishing demographic growth throughout the settlements along the line. Kfar Aza has doubled in size, next year it will have a thousand people, of whom 250 are children. It managed to maintain an education system despite all the crises. There are regional councils here that knew how to overcome financial crises and provide good services. There is a college here that is now a huge anchor of employment, of education and it also brings young people here. And another patent invented by the Turks – a train. I arrived today from Tel Aviv in a little over an hour."

The public that comes to the kibbutzim are mostly settled people above 30 who have left the big city.

Harmesh: "Of course it's also a matter of money, living in the city is expensive. I also had the privilege, as a legislator, of passing the law of tax benefits for those living around the Gaza Strip. But money is not enough to come to a place with bombs falling on your head."

Sabag: "Pinchas is usually shy, but on the day we accepted 20 people for membership at once, in June 2016, he was the last that I went to thank, simply because I knew that when I reached him I wouldn't be able to stop crying. He ran all over the country from north to south to open another way, another path, to get another signature. Not everyone believed in us and he was the one who pushed."

What do you think is the basis for the connection between you and these communities? Is it simply a human encounter or are there shared beliefs?

Wallerstein: "It took me a while to move from a mental state to an emotional state. Everyone I talk to will say that they are in favor of unity. But to transfer it from the head to the heart is a different story. It is to be sure without a doubt that I admire Oshrit who lives in Nahal Oz, or Renana Manir Oz of Hashomer Hatzair. You go through some kind of switch that requires you to refer to a pioneer or a Zionist. Then, when you get to the political debate, you remember that some of them are people you cherish and appreciate and try to understand what deters them so much. I hate the word compromise, from the values side. It is not true."

Why?

"Because in order to build a society you need everyone. If you want a healthy society, you need the majority of the public involved. A society that is only left or only right is a disaster for the country. What can be done when politicians intensify the wars and destroy lives? But as far as I'm concerned… I didn't like it when they formed the current coalition, and I don't blame one side, because it doesn't matter to me who is 40 or 60 or 20 or 80 percent to blame. We are here, and that's why I also wanted us to be interviewed here."

This article was translated from Hebrew by Etz Greenfeld.