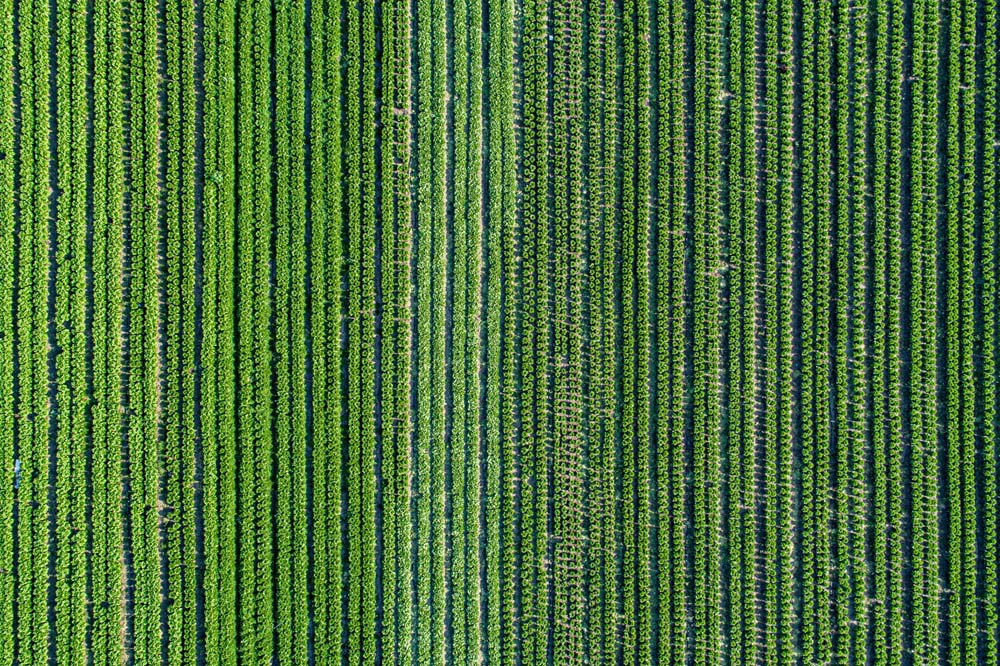

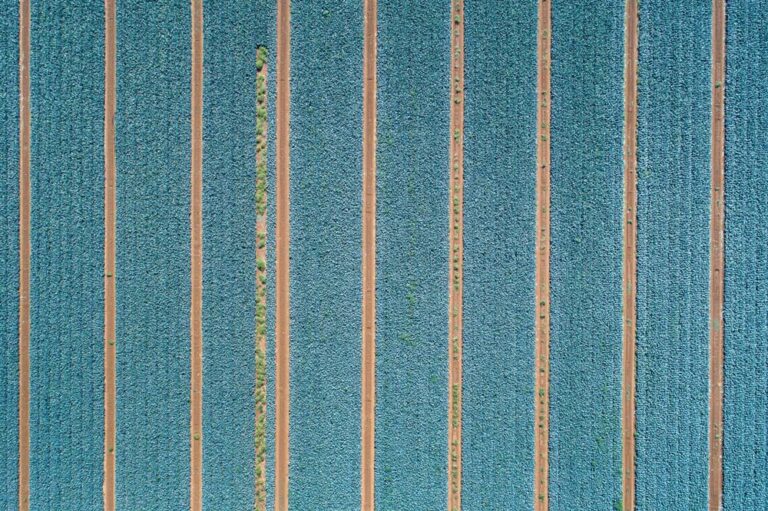

Cabbage beds in the Golan Heights become a spectacular turquoise carpet, mixed fields turn into an iridescent patchwork, yellow paths between almonds create incredibly precise lines. Even the black nylon sheets sprinkled with drying watermelon seeds in the Hula Valley look like a painting created by the hand of an artist.

"These fields that I photograph are palettes of color and texture, which is very interesting to me," says photographer Ilan Nachum, 63, who lives in Tel Aviv. "It's a combination of my love for agriculture, and something that is really more pure. Dealing with texture, color, geometry, is the basis of photography itself."

He photographs these vast picturesque areas using a drone. "I realized that I had to go up high, because when you go up high, you can see far."

"The view from above is inherent in me"

His first encounter with professional photography, with printing in a darkroom – at the age of 12, in a class at a community center – did not last long. He always had an attraction to agriculture. During his childhood in Jerusalem, he loved family visits to the kibbutz. "There is something amazing and beautiful about the kibbutz," he says.

During his military service, he knew kibbutzniks who were, according to him, "the best guys." He met a new friend from a kibbutz, with whom he would volunteer to work on the kibbutz farm.

After the army he studied law, but two years later, he realized that photography interested him more. He loved cinema, often going to the movies at the Jerusalem Cinematheque. To combine his two loves of photography and cinema, he went to study cinematography at the Beit Zvi School for the Performing Arts.

"After school, I immediately got involved in the industry,” Nachum explains. “I was a photographer's assistant for a few years, as is the standard path of development. Starting in 1992, I started shooting independently, mainly commercials and music videos. I went through all the fields; documentaries, features, short films."

In 2012, after 20 years of cinematography, he decided to switch to still photography.

"Some kind of need for personal expression was born,” he explains. “As a cinematographer you are a performance contractor, you express the desires of the director. You can be excellent, with the soul of an artist and crazy technical abilities, but you are always at the service of someone else. If you want to express something of yours, you have to direct. In cinema there are many people, editors, screenwriters, and directors; it's a complex operation. With stills, all you need is a camera and you’re ready to go."

At first, he photographed food and book covers, taught photography, worked as a photographer for the food magazine "On the Table," and photographed magazines for architects and designers. "Today we are used to food being photographed from above,but I was one of the first to take pictures like that," he says with a smile. “I did photographs for Chef Meir Adoni, for the design magazine 'Domus.’ They place the food down, and when photographed from above the food becomes completely flat and painting-like."

"Good photography doesn't need to be explained"

His first photo book was released in 2014. "I was looking for a photo book of Tel Aviv. I couldn't find it, so I said I would make one," he explains. His book "Tel Aviv" describes, through pictures, a day in the city. Instead of page numbers, the time of day appears. Besides the time, the location of the photo appears, without any unnecessary details. "Good photography," he tells his students, "doesn't need to be explained."

Later he returned to agriculture and the kibbutz. "It started with a series," he recalls. "I was at Kibbutz Gesher one evening. I had a camera, so I started taking pictures of some houses at night. My attraction to kibbutz documentation developed, and I went to several more kibbutzim. Meir Aharonson, who was the curator at the time, saw this at the Ramat Gan Museum, and told me it was interesting, he wanted to see more of it. So I continued, and was also drawn towards agriculture in general."

In 2021, he released the book "Wine Country", in which he shows the grape vineyards and wineries throughout the length and breadth of the country. "I broke down all the photographs of the vineyards into the seasons, and returned to the same places every season."

"The farmer is the new Jew"

Nachum explains the difference between detailed documentary-style photography, and taking zoomed-out photos of fields and vineyards from a drone.

"It's not art that aims to document, but rather to give a new point of view,” he says. “I bring a cleaner look, detached from the documentation. It's still a form of documentation because the essence of photography is to document things that exist, but I manage to show a unique aesthetic value in it."

According to Nahum, the farmers are not aware of the beauty of the fields they labor in each day.

"I believe that every action has an aesthetic value, conscious or unconscious. The way you cut a salad, the way you fold a shirt, and the way you plow the field; even if you are not aware of the action, some aesthetic value is always derived from it,” he says.

“I really like the aesthetics of the farmers. They have to plow straight because it's the most efficient method to work the field. When the lines are even, they create this kind of embroidery, like knitting or weaving, and depending on the type of crops, you get all kinds of fabrics. It's not planned, but the results can be amazing."

Looking from above, he explains that the fields farmed by Jews look different from the fields belonging to Arabs. "The social issue and the political issue have an aesthetic expression. Jews in the Golan Heights are given 300-400 dunams to cultivate. [The Arabs] have to settle for an even smaller portion each time and divide it between family members."

While photographing from a distance allows one to detach from the context, Nachum often talks about a deep connection to the land.

"I am very connected to nature, very connected to the Land of Israel. Settlers and right-wing people are appropriating the Land of Israel, but I probably know it the same amount as those who see themselves as great patriots,” he says. “I feel that I tell the local story, an important one. I see farmers as true pioneers. Through agriculture, we built the country and created borders for it. For me, the farmer is the new Jew."

This article was translated from Hebrew by Noah Mirkin.