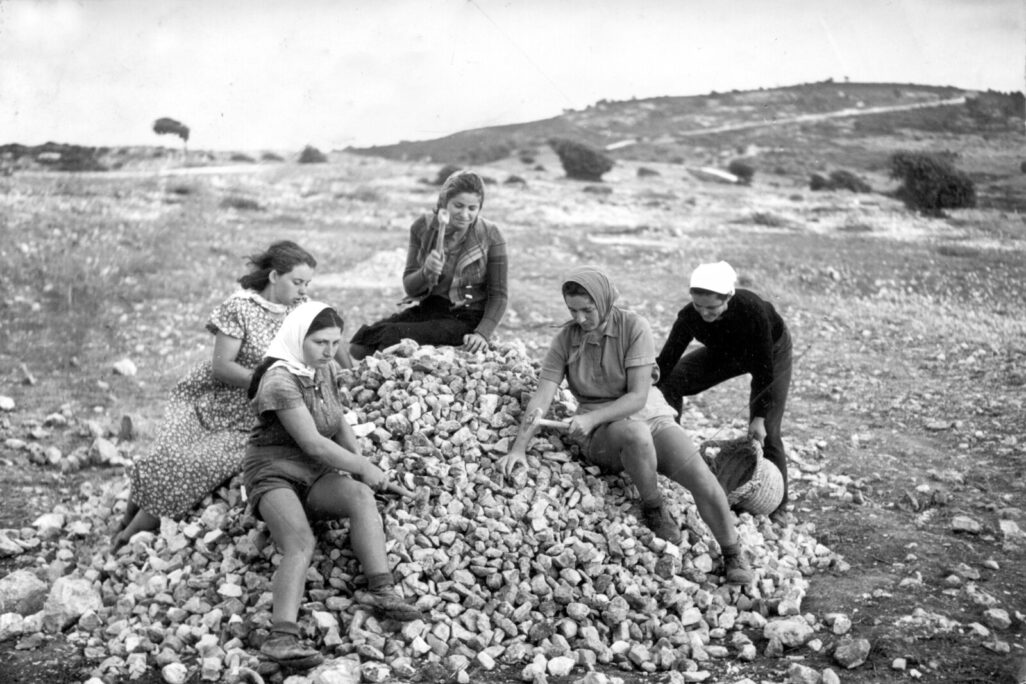

When Dr. Tamar Schechter was researching Rachel Katznelson-Shazar, labor unionist, political activist, writer, and founder of Israel’s first women’s magazine "Davar Hapoelet," she came across a wellspring of forgotten materials in a file named "Female Members of Kibbutz:" a compilation of personal writings from one hundred women of the United Kibbutz Movement, who founded kibbutzim and lived the bittersweet lives of the early pioneers.

"This file is mandatory reading for every woman living in this country," Schechter told Davar. "30 years before women's writing was understood in the West as what we now call the second wave of feminism, decades before the struggles for the right to abortion, for women's right to their own bodies, one hundred kibbutz members stood up one after the other, opened up these issues, expose the desires of their hearts in deep texts, gently and with a lot of wisdom. There is a protest in these documents, there is hope, there is a lot of love and pride for the collective enterprise, and of course there is also pain."

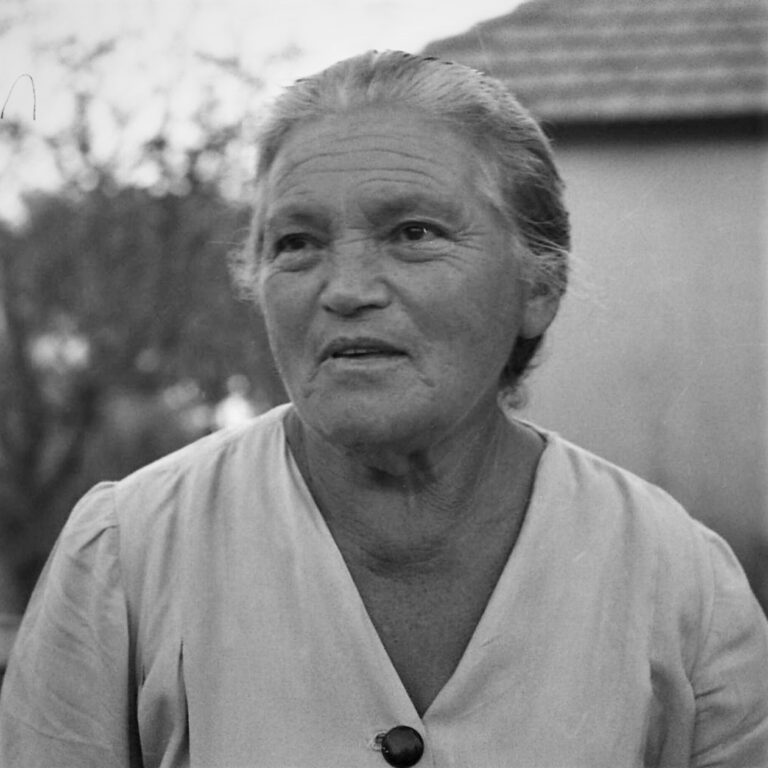

Schechter, 78, found evidence that this was the first of many files, and turned her discovery into a research project. Her research is now being published in the book "To Draw From Silent Lips – Studies of the 'Female Members of Kibbutz' File" published by the Kibbutz Movement archive Yad Tabenkin.

"Israeli feminism grew up in the Histadrut and the kibbutz," she said. "In the early 1930s, shortly after Virginia Woolf published her book 'A Room of One’s Own', two kibbutz women understood the revolutionary importance of female writing and the publication of the life stories of their pioneer friends, and dedicated a decade of their lives to publish an illuminated file of kibbutz members."

The editors’ vision

The compilation, first published in 1943, was edited by Lilya Basevits and Yocheved Bat-Rachel, who were among the leaders of the Histadrut and the Kibbutz Movement.

"In this file, the society will narrate its life," reads the opening of the book. "Let the society say what is in its heart, its thoughts and aches in the questions of the kibbutz and the movement.

Basevits and Bat-Rachel immigrated to Israel from Eastern Europe after World War 1, in the Third Wave of aliyah.

"They were strong women and leaders even in the diaspora," Shechter explained. "Bat-Rachel was an activist in the He-Chalutz [Zionist pioneering] movement, Basevits was an underground Zionist activist in Russia and was even imprisoned for it. They came to Israel and were among the founders of Kibbutz Ein Harod and the United Kibbutz Movement. Over the years they held leadership positions in the Histadrut's Women's Council, the Zionist leadership and the United Kibbutz Movement.

“Basevits was a member of the editorial board of 'Davar Hapoelet', the first women's monthly magazine in Israel, for around 40 years from its founding in 1943,” she continued. “During the founding period of the magazine, Bat-Rachel and she conceived the dream of giving voice to female kibbutz members – a book that would contain their pioneering stories."

The few who responded to the call for submissions were mostly women who already published their words in kibbutzim bulletins and Davar Hapoelet regardless. Basevits and Bat-Rachel insisted on giving a platform specifically to women who don't usually tell their stories, and to that end they met, interviewed, and convinced women to speak for several years.

At the launch of her first autobiographical book "If Only an Echo" (1981), Basevits said: "My vocation in life was not only to write but also to dictate. I put a lot of initiative and effort into this, I encouraged friends to write or take notes from their experiences. And I don't know what I did more: whether I wrote myself or I wrote others."

The project saw the light of day after almost a decade of hard work, and over the years became a milestone for the kibbutz movements and the women of Israel.

The confessions: from the first kiss to breastfeeding friends' babies

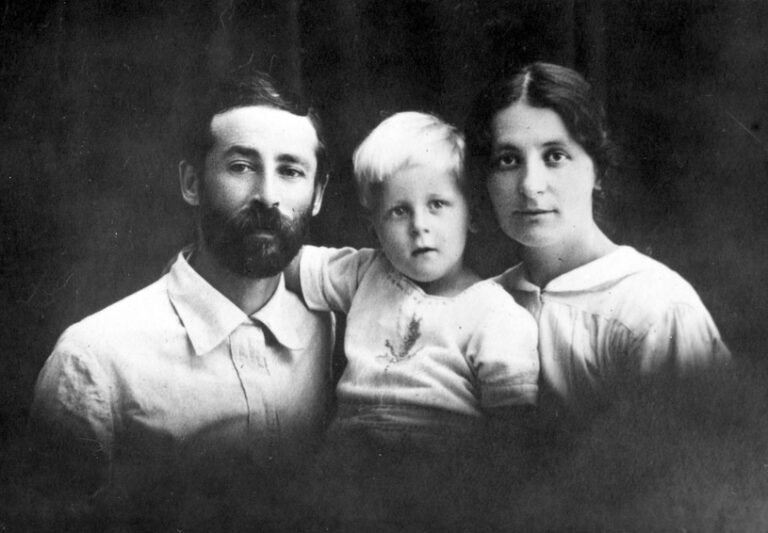

The file opens with the life story of Atara Sturman, one of the few women accepted into the Hashomer defense organization, which was already seen as a chauvinist organization at the time the file was published. She deals with the stigmas of the male fighters against the women, while revealing intimate details that were not usually shared at the time, such as her first kiss with Haim Sturman.

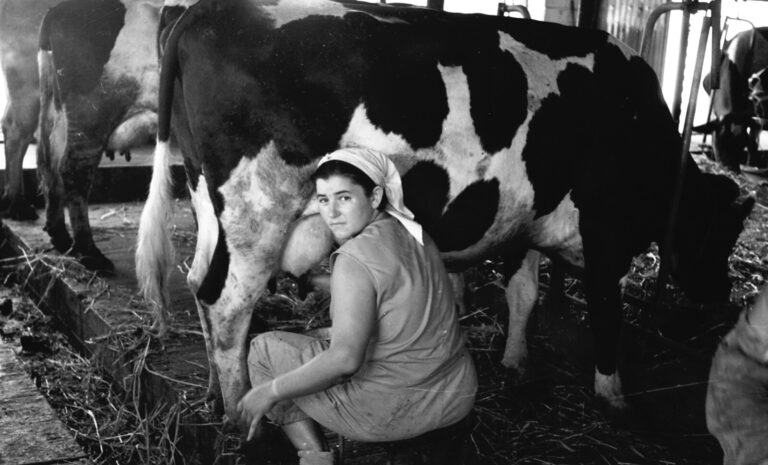

She tells about failed pregnancies, about life as a pioneer in Moshav Tel Adashim and early settlements Sejera and Kvutzat Kinneret, about her first appearance in Ein Harod with her baby Moshe in her arms, which provoked resistance amongst the pioneers. She includes stories about how the first cooperative nursery developed, established right in the marshes of Emek Harod under conditions of constant security threats, malaria, and countless other problems.

"Many dilemmas fell on the shoulders of Atara and her friends, the women of the second aliyah," Schechter explained. "Already in their third decade of life, they were considered the elders of the tribe, and they had to teach the young women how to take care of babies in the absence of their parents who remained in the diaspora.”

Schechter continued to describe how women on the kibbutz would breastfeed each other’s babies in the case of one mother unable to provide milk, explaining that “they saw this as an expression of their commitment to each other and the sense of kinship of the kibbutz members who are like family. Basevits wrote about this in one of her notes: 'A member who shirks her duty or fulfills it unwillingly, [it will] never be forgotten.'"

Schechter noted that there was extensive documentation about dilemmas of breastfeeding; that Atara wrote down her personal deliberations about feeding her friend’s child, the exhaustion she felt of providing for two babies, and the fears of its physical toll on her body.

"Outside of this file, this is a subject that almost nothing was written about in those days, certainly not from the eyes of the mother who breastfed another child, or of the mother whose son was being breastfed. Both of them suffered from the process," she said.

There were other taboos on women on kibbutzim. Limiting children was encouraged via contraception and abortion, "due to financial difficulties and perhaps pioneering ideology," Schechter explained.

"Women who gave up having children at all, or forwent birth of a second and third child, they internalized the conventions of society," she continued. "The ardor of pioneering fulfillment, which took over them as it did the men, softened the feelings of pain and frustration. Even women whose maternal desires were intense, internalized the accepted social concept, and recognized the need to mobilize the economic and social resources in another direction."

In contrast, Eva Tabenkin, wife of leader Yitzhak Tabenkin, resisted the social pressure to terminate pregnancies, and "demanded that the women be fully sovereign over the decision whether to continue the pregnancy or terminate it," Schechter said.

"Her writing indicates that she is aware of the shame and confusion in the souls of the women and the dilemma they faced – to listen to themselves or to respond to the social demand to give up the pregnancy."

Reliable documentation or kibbutz propaganda?

The compilation has been previously used as source material by researchers, on topics such as early public education, the status of male pioneers’ wives, and the integration of women in defense, agriculture, and industry. However, according to Schechter, these researchers treat the book as a collection of literature or even kibbutz movement propaganda.

"Some claimed that this book is an advertisement for the kibbutz and does not tell the truth, as if the purpose of the file is to convince women to join the kibbutz,” she said. “Other researchers claimed that it is indeed an advertising book, but one can also learn from its truths about the life of the women in the kibbutz."

Schechter does not believe the compilation should be classified either way.

“I believe in the editors, who explicitly wrote that the goal of the book is first of all the women, and the dialogue between the women and the men in the kibbutz. That is the goal. Beyond that, I am not looking for the facts. Their struggles have already been researched and everything has already been told. I am looking for what is written between the lines; the mental reflections of the hundred women who participated in this file,” Schechter explained.

"I use a method of qualitative research, in which in-depth interviews are conducted and through which I break into the depths of the interviewees' souls. So it is true that I do not have female interviewees, the speakers in the file are no longer alive, but I have evidence that they left behind. I am careful not to put words in their mouths.”

The unique female voice

The file was a huge success at the time, causing waves among the leaders of the Yishuv, including David Ben-Gurion and Abba Ahimeir, intellectuals and kibbutz members. Many praised the unique point of view of the writing and the exposure of the world that was hidden from the public eye. It was printed in three editions over two and a half years, and was a sort of local bestseller. Kibbutz members testified themselves that their membership changed after reading the file.

But the file's contribution to women was the most important. Already in its first days, the compilation crossed borders and reached the Yishuv recruits in the British army. Chana Agmon and Leah Krupnik, who were serving in Egypt at the time, wrote about the happiness and hope that the writings brought to them and the soldiers who served with them.

"It is important to disseminate it to all the Hebrew soldiers," Leah Krupnik wrote in Davar in March 1944, "because it tells about the participation of the female members in the building of the country and their suffering, which is not always known.”

Moshe Musinzon of Kibbutz Naan, who served as part of the British brigades in Italy, was also very impressed. "I don't know why," he wrote in February 1944, "but the way you are able to write, no man will ever write."

Haviva Reik, who completed parachute missions in Slovakia, took the file with her on a mission from which she did not return, despite the requirement not to take heavy objects. She received it as a parting gift from her friends at Palmach on the night she left for the mission, and the book accompanied her on her final journey.

On the eve of her capture in the mountains of Slovakia, the book was buried along with her walkie-talkie and other personal items in the forest. It was found after the Second World War, and today it is displayed in Beit Haviva, the center that was built in her memory at Kibbutz Ma'anit.

This article was translated from Hebrew by Hannah Blount.