In the Asher family, the Iraqi identity is a source of pride. The parents grew up among Arabs in Baghdad and spoke the Judeo-Iraqi language. More than 70 years later, the second generation conceived a card game, "Fours in Pajamas” in order to learn the language and as a salute to their parents' cultural heritage. Davar sat down with the Asher family to hear about their family legacy through their game.

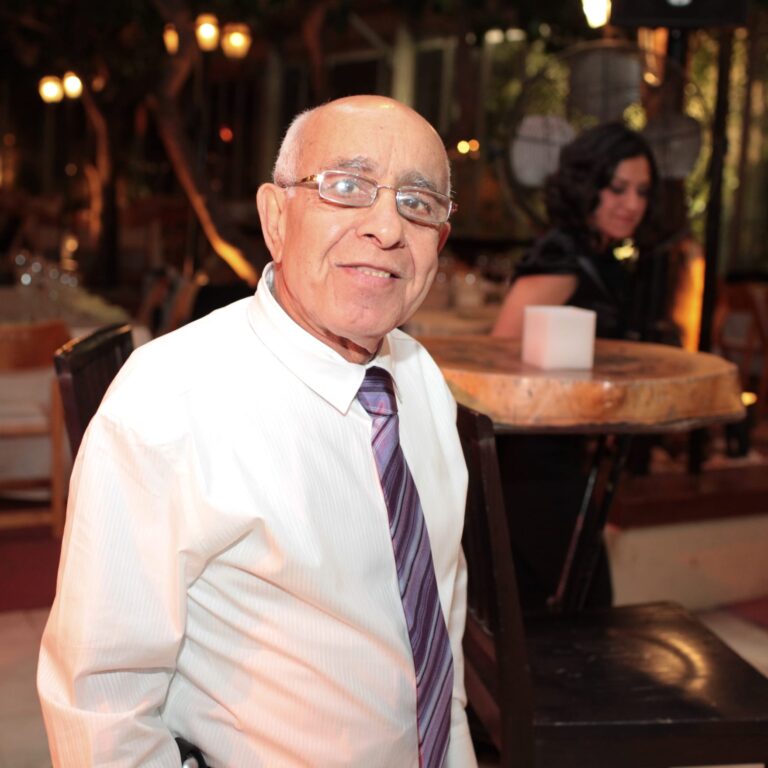

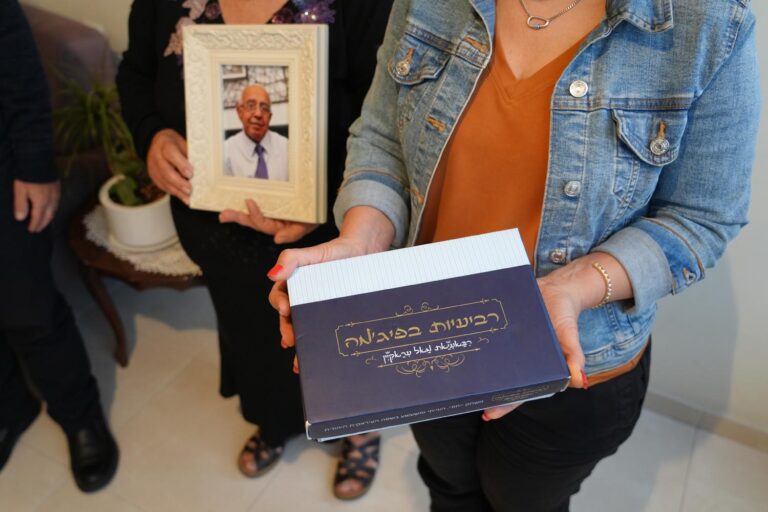

The game is dedicated to the memory of the patriarch of the family, Reuven Asher, who died in 2021. "We feel a commitment to the preservation of our father’s mother tongue and the Iraqi culture that came from it," says the eldest daughter, Sharon Borg. "Just as you donate in a synagogue in someone's memory, this is how we commemorate our father.”

The lizard on the wall

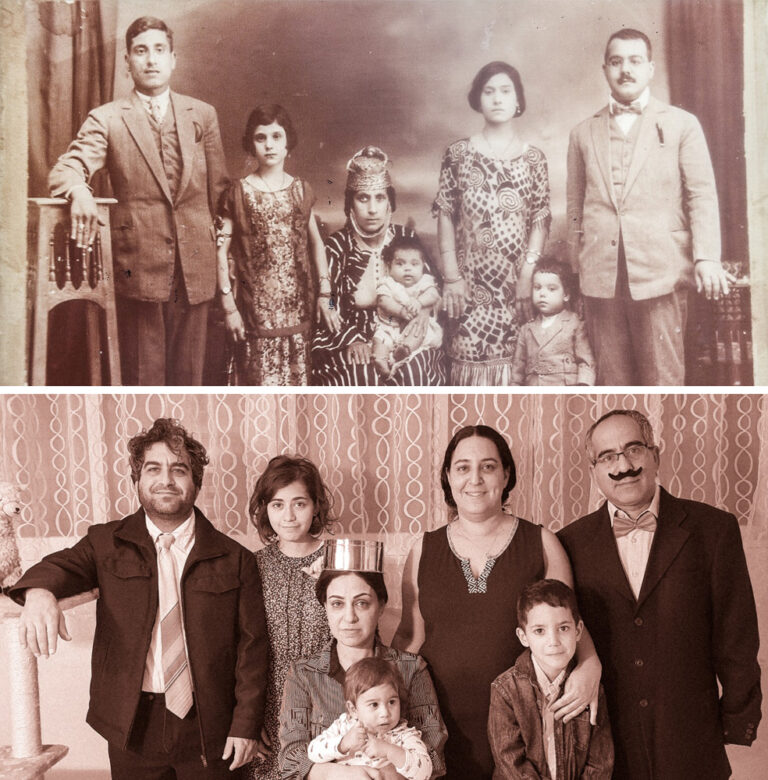

The matriarch of the family, Drora Asher, 78, was born in Iraq and immigrated to Israel with her family at the age of six as part of Operation Ezra and Nehemiah, the mission to evacuate 120,000 Iraqi Jews. She does not have many memories of her early childhood in Iraq.

"We lived in Baghdad in an environment where there was no real Jewish community," she says. "My mother was a seamstress for the whole neighborhood, and my father worked in gold, a jeweler. He wouldn't let us go out. He would say that our friends are our siblings, and close the door . I didn't have any friends outside. They didn't send us to school, only the boys."

Drora explains that there were communication barriers between Jews and Arabs.

“We didn’t speak Hebrew at all. There was Judeo-Arabic, and Judeo-Iraqi. We understood them, and they didn’t understand us,” she says. “The Jews had a warning code against the presence of Arabs, they said ‘there’s a lizard on the wall’, which means ‘be careful, there is an Arab here who is listening.”

After immigrating to Israel, the family continued to speak Arabic at home, but outside, Drora was forced to speak only Hebrew. "It's not good," she says. "Another language is another world. What I know, I wanted to pass on to my children. Kudos to the Russians who came to Israel, they only spoke Russian to their little ones."

Rami, say Coca Cola

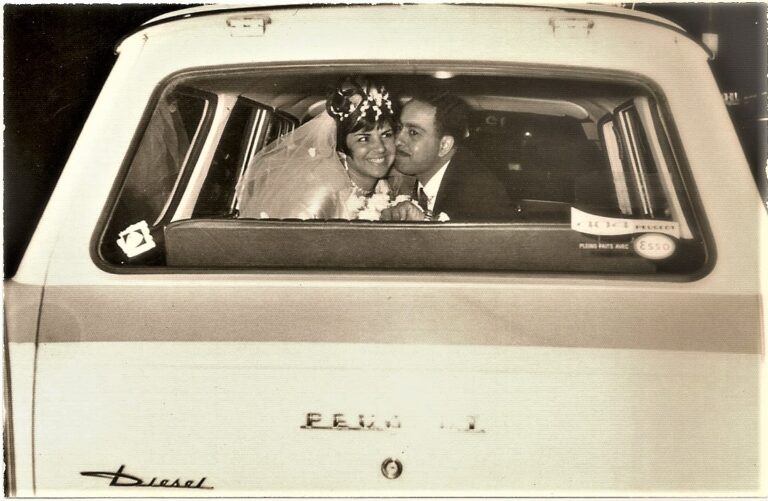

Reuven and Drora married in 1969 and moved to live in Ramat Gan, where their four children were born: Sharon Borg, 50, works in marketing; Rami, 48, a pharmacist and linguist; Meital Pinchas, 44, microbiologist; and Gil, 37, a computer expert. All four of them remember the "language of their parents" very well.

Iraqis, as the cliché says, do not leave Ramat Gan. "At two in the morning, you shout 'Yehezkel, [a traditionally Iraqi name],'" Sharon laughs, "and everyone gets up."

At home, the Iraqi language was widely spoken. "Father never had an accent, he always spoke Hebrew,” she says. “But mother didn't let him. Mother loved the language, so she made him speak it too."

"When Rami was born, as soon as I brought him home, I started speaking to him in Arabic,” Drora recalls. “In Iraqi, the ‘kuf’ (a Hebrew letter) sound is very strong, and when Rami was a year old, all the children in the family would stand around him and tell him: 'Say Coca-Cola,' and laugh at the way he pronounced the ‘kuf’."

"We thought that this language was our private language, and the more we were exposed, we saw that even the slang we thought was domestic, exists in almost every home that speaks the language,” Rami adds. “We realized that this is not just a private or family joke, that there are other people who speak the same language."

Dudu Tassa made all the difference

Apart from just the language, it took the children time to connect to the culture. “I have connected only in the last five years,” Sharon says. “Before that, I found it difficult when mom and dad would listen to songs in Arabic."

“The one who made me connect was Dudu Tassa, [Iraqi and Kuwaiti Jewish singer]” she continues. “His music was like a bridge, the rock and roll he put into it. Thanks only to that did I start to connect. Since then I slowly started listening to Arabic music and enjoying it. It made me explore the culture and my roots more.”

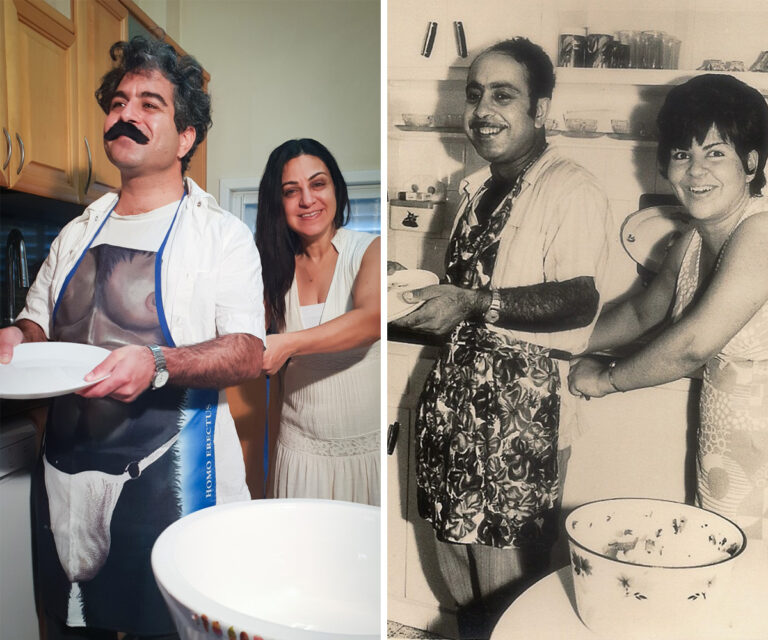

Reuven and Drora stuck to their Iraqi culture. On the occasion of their 50th wedding anniversary, the children decided to prepare a one-of-a-kind gift for them: a card game which is full of words in the language they knew and loved.

"As soon as the idea came up, everything was already running through my head," Rami says. "I have a master's degree in language, I deal with language, Arabic, linguistic editing. This is my true love. Dealing with language, with linguistic humor, this is my field."

"Rami expresses himself through this game,” Sharon adds. “He has this sense of humor, this wit, this way of thinking, so he invented the game."

The family joke becomes a serious matter

“At first we made one non-committal copy of the card game. We collected all kinds of images from Google, we didn't pay attention to the spelling and transcription," Rami says. But after their father passed away, in 2021, the idea developed and grew.

"Father was a man of the people, he saw each human being,” Sharon says. “He had a phone book and he would call people every holiday, birthday, anniversary, even the cashier at the supermarket. So many people of all ages came to his shiva, all the neighbors were here.

“You see there are seven floors here, there are families here, young couples with small children, and I think, what are the chances that such people somehow connected with him? And they came and told us things about him that we did not know. Many told us about a father we knew, but to hear it from so many people, it was very exciting."

The death of their father brought about a change. "Since Dad passed away, we have tried harder to be exposed to Iraqi culture,” Meital explains. “We went several times to Arab music concerts, to lectures, to get to know the people and the culture better, and meeting as a family is also important to us. Joint cultural meetings after our father's passing are a kind of a commemoration of him. We miss him very much in these situations."

During the shiva, members of the extended family were exposed to the game. "It really made them laugh," says Sharon. "It was a bit unpleasant, because we were at our father's shiva, but we realized that there was something wider here than just our immediate family. They asked us to print a copy for them as well. So we decided to print copies for the rest of the family.

"When we were working on it, we realized that we can't just use images from Google, that it has to be done properly. Rami had more and more ideas, and that's how it expanded."

"For the photos of the cooking, we stood and cooked, and Sharon's husband took pictures of the dishes,” Drora explains.

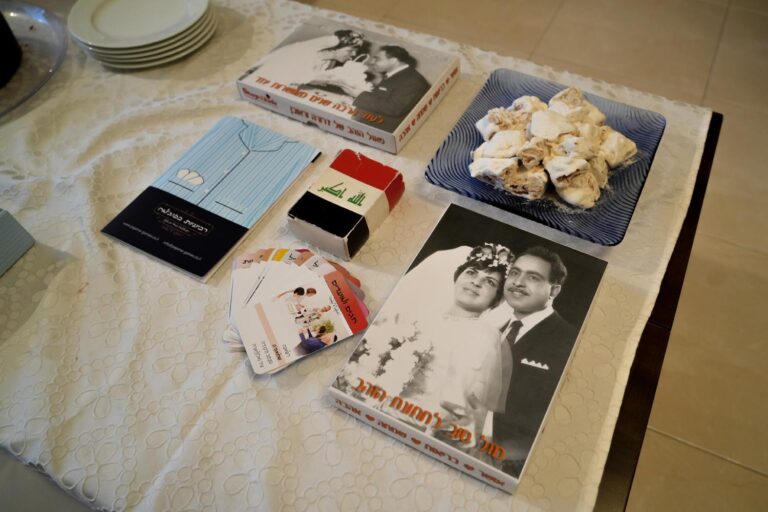

The new and improved version includes 208 cards that are divided into 52 different, unusual categories. Foods such as kubbeh and mahbuzat (pastries); chawain (animals); greetings and wishes, holidays and dates; curses,and badlak dakhtor (how to complain to the doctor).

They made 50 copies for the family, and from there it spread. "Each time more and more orders came, and we would produce more copies," says Sharon. "I didn't believe at all that we would be able to sell everything, and so far it's going really well for us. We also sold a copy to Tel Aviv University, for research purposes."

Among the playing cards there are words such as dishdasha (gown), buma (owl), charpaya (bed), nazach chachma (a sewage cleaner), cheng (prosthetic teeth), jud (rubber bottle hot water), siana (dirt), kizarkort (to suffocate), karnabchit (cauliflower), zarntakh (snail), kafikhir (a large slotted spoon), lachif (down blanket) and chakchaka (rattle).

They set up a website for the game. "We wanted as many families as possible to be exposed to it, enjoy it and learn from it," says Rami. "It was not any of our jobs on a daily basis, but we all united for this purpose. I used dictionaries and professionals.

“We preferred that the translation of the words not be shown on the cards themselves, but in the booklet attached to the game,” he says. “It is important that people learn to read and pronounce the word in Arabic, and not be tempted to just read the Hebrew translation. The game booklet also contains a link to a video where you can listen to the pronunciation of the phrases in the game."

"The reactions to the video are great," says Sharon. "People burst out laughing, and this is our way of preserving the mother tongue and father's culture."

On the game packaging, there is an illustration of their father and a dedication to his memory. "In the presentation of the pronunciation of the phrases, we put pictures of him with his family. It's a language that isn't just words, it's the essence, it's like your soul," Sharon adds.

This article was translated from Hebrew by Nancye Kochen.