"I was amazed at the pettiness of the members. Every little thing became a 'problem' and there was a certain amount of 'screwing up.'" This is how Zivia Lubetkin, one of the leaders of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, described her impression of life in the Land of Israel in 1946, in a letter to her partner and co-leader of the uprising, Yitzhak Zuckerman, who was to immigrate to Israel a year later.

The critical tone of Lubetkin, who only three years earlier led one of the largest armed resistances to the Nazis, reveals the tension in which Lubetkin and Zuckerman lived after they immigrated to Israel, and the many challenges they encountered in Israel after the uprising and the Holocaust: the establishment of a kibbutz, the shaping of memory and the education of future generations, social and national struggles, and also “small” problems of everyday life.

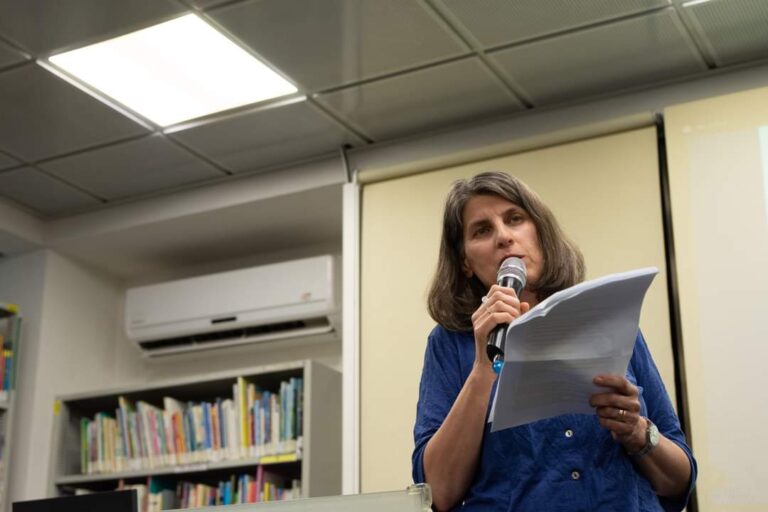

"The difference between the tension of the Holocaust and life in Israel is not exactly an 'either-or'. It is much more complex than that," said historian Dr. Sharon Geva, author of the new book "Everything Else Is Immortality – The Story of the Lives of Zivia Lubetkin and Yitzhak Zuckerman,” which recounts their lives in Israel after the Holocaust.

Rebuilding after the uprising

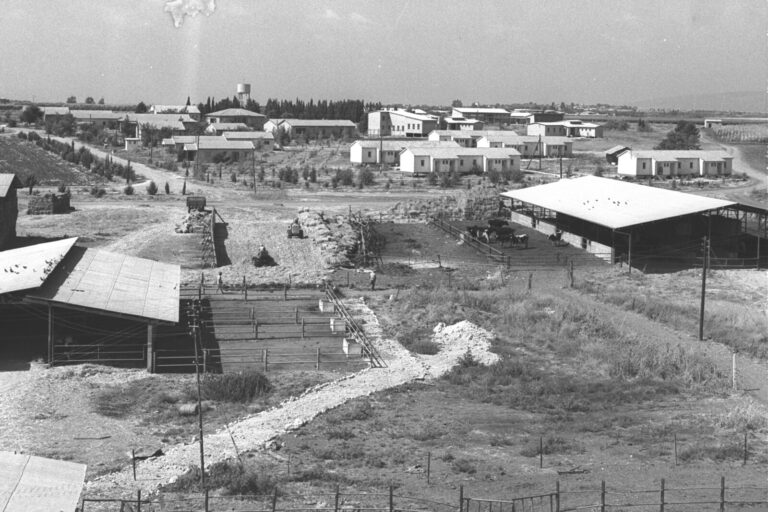

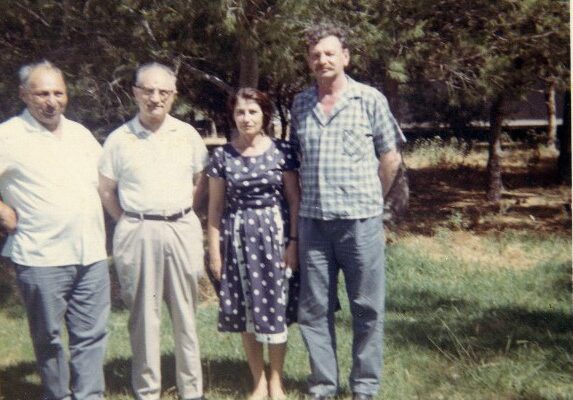

Lubetkin and Zuckerman were members of the Dror youth movement in Poland, and were among the leaders of the uprising against the Nazis in the Warsaw Ghetto in 1943. Zuckerman was outside the ghetto during the uprising itself, and took charge of supplying weapons to the uprising, while Lubetkin remained among the fighters, and was among the few who survived. At the end of the war, they were active in the Bricha (“Escape”) movement, which worked to help Jews to immigrate to Israel. They themselves then immigrated to Israel and were among the founders of Kibbutz Lohamei HaGeta'ot (the Ghetto Fighters Kibbutz) located in the Western Galilee, and the Ghetto Fighters House – a museum bearing witness to the legacy of the uprising and the first museum in Israel to commemorate the Holocaust. Their relationship began during the war, and later they got married and started a family.

Geva chose to focus on the life and struggles of the two after the Holocaust.

"The questions of how to carry on with their lives are very big, issues of a settlement being created from the ground up, of a kibbutz that needed to establish its own membership and community,” she explained. “Both were also active in national issues – the reparations agreement from Germany, the Eichmann trial, the relationship between Israel and Germany and the challenges of the memory of the Holocaust in Israel. The Ghetto Fighters House that was established in their kibbutz competed with Yad Vashem for the first place, and this was a big thing."

According to Geva, the point of her book is to deal with the gaps between “historical challenges and the difficulties of everyday life, some of which can be considerable.”

“It is about the tension of how to build a life after this huge event, juxtaposed alongside the fame and glory they received in Israel – how do you live with this?” she continued. “They did not plan for this to happen to them, they didn't think they would even survive the uprising or the Holocaust.”

Between Masada and Warsaw

One example of the daily tensions between the memory of the Holocaust and life in Israel is a debate at a 1964 kibbutz meeting of Lohamei HaGeta'ot, about the participation of the 10th and 11th graders in the excavations at Masada, to be led by the archaeologist Yigael Yadin. The kibbutz secretariat, led by Zivia, objected to their participation in the excavations, but some of the members thought otherwise.

"It will instill in them the desire to get to know the country, enrich their experience, there is so much more to be gained by it. How will the youth be molded if it is not there?" said one of them. Lubetkin justified the opposition from the secretariat: "It is hard to see how the excavations will be an experience."

Zuckerman disagreed, referring to the tragic heroism of the Masada story, where Jewish fighters committed mass suicide rather than submit to the Romans. "The decision of the secretariat is puzzling to me," he said. "Masada should not be compared to just any historical site. A week of participating in the excavations could contribute a lot to the children's education."

"One gets the impression that he supported the participation of the youth in the excavations, because he saw it as an opportunity to take part in a national undertaking and give the youth a unique experience," explained Geva. "But in Lubetkin's eyes, it was simple. She did not see Masada as an example or as a role model: neither during the Holocaust, as a leader of the underground who did not spare herself, nor from the distance of time as a fifty-year-old woman, mother of two teenagers, and the secretary of a kibbutz."

Still, Masada did not let the two go. In 1963, member of right-wing movement Beitar, Chaim Lazar-Litai, published a book about the Jewish Combat Organization in the ghetto, calling it “Masada of Warsaw.” In 1968, Rachel Yanait Ben-Zvi, wife of the second President of Israel, Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, wrote a letter to Lubetkin and Zuckerman in which she stated that "Masada will not fall a second time.” In his 1973 speech at the annual memorial to commemorate the Holocaust and heroism, Chief of Staff David “Dado” Elazar compared the heroism of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising with the heroism of Masada.

The ghetto fighters' struggle continues

It came as something of a surprise to Geva to uncover in her research just how fragile Kibbutz Lochmei HaGeta’ot was, with difficulty recruiting both members and funds.

"On the one hand – these two are 'Heroes of the Holocaust and the Rebellion' with their accompanying public status, and on the other hand, it was surprising to see how hard the work was, and how much they had to go back and forth in order to get money,” she said.

Geva cites the example of the correspondence between Rachel Yanait Ben-Zvi and Zivia, where Ben-Zvi expresses great appreciation for Zivia. But when it gets down to it, politics wins out, as Geva explains: Ben-Zvi is the president's wife, from another party, and therefore supports the National Memorial Authority, Yad Vashem, not the Ghetto Fighters’ House.

The difficulty in recruiting new members, while shared with other kibbutzim, was particularly difficult in Lochmei HaGeta’ot because of its strong association with the older generation of Holocaust survivors. This had a deep effect on the kibbutz.

"In the 1960s, the state of the economy almost totally depended on restraint – a far cry from the days of an established kibbutz,” Geva said. “This represented a generation of people who were older than members of other new kibbutzim, and the fact that there was no middle generation between the generation of the parents and the children, created a very heavy burden there."

Remembering the old days

In the book, Geva describes Zivia and Yitzchak's room, where hundreds and thousands of guests would come over the years, many of them uninvited, "passers-by, or Israelis who happened to be around, or perhaps distant acquaintances, all of whom would just turn up, and it was impossible not to let them in.”

“Zivia and Yitzhak’s room was also full of very close friends, who would keep coming back,” she went on. “They would talk about the time of the Holocaust and the underground, and also about memories of Warsaw and Krakow before the Holocaust. It was like sitting shiva."

She clarified that it was like a shiva in its comforting aspect.

“At a shiva we also laugh, we also remember and we recount the same stories over and over again, and here it really didn’t end; it was an experience that brought a certain comfort,” she said. “It's the kind of thing that today it is harder for us to understand.Today calling can already be seen as a kind of invasion of our privacy, and even more so when people simply just turn up at the door."

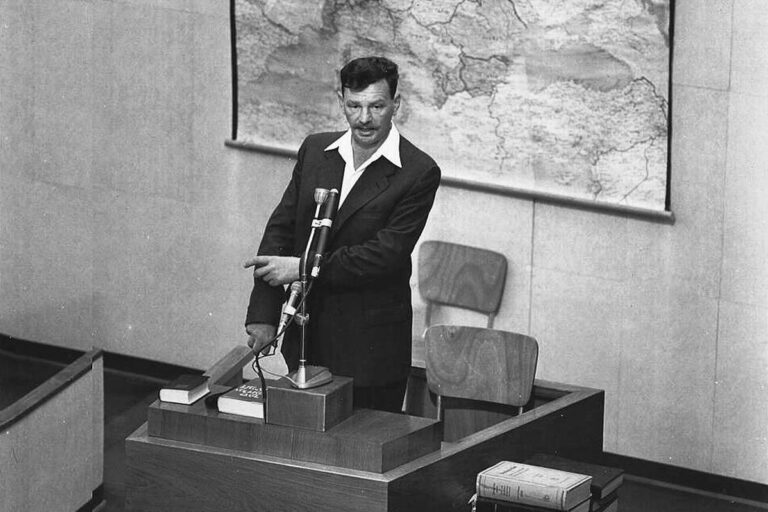

The Eichmann trial

One of the stories that Geva reveals in her book is the quiet drama behind the testimony of Lubetkin and Zuckerman in the Eichmann trial. Miki (Menachem) Resh was a police investigator in Unit 06, which was established for the purpose of the trial, and a Holocaust survivor himself. After quite a concerted campaign, Lubetkin and Zuckerman agreed to testify, and Resh was sent to the kibbutz to collect their testimonies. However, in his report to the unit, Resh recommended that they should not testify in the trial at all.

"I am not sure if his knowledge is based on actual memory, or if he is relying on what he learned after World War II from documents," Resh wrote about Zuckerman. "He describes various events beautifully, but tends to spin them out. It is difficult to understand precisely what he saw himself and what came to his attention through hearsay."

He wrote about Lubetkin that "she does not remember dates, times and numbers at all. Everything that was said in her testimony was taken from books or from the mouth of Yitzhak Zuckerman. For this reason, her chronological account is also not good."

Resh's opinion was rejected. Lubetkin and Zuckerman became key witnesses in the trial, recounting the underground and the rebellion from the witness stand. The trial itself had a special nature, as a combination between a criminal proceeding to determine Adolf Eichmann's guilt and punishment for his crimes, as well as a public accounting with both Israeli and international educational and political implications.

"What intrigued me was the personal letters"

Geva, a senior lecturer at the Kibbutzim College and a historian at the Ghetto Fighters House, cannot pinpoint the exact moment when she decided to write a biography of the Lubetkin Zuckerman couple, which will deal exclusively with their lives in the Land of Israel, after the Holocaust.

"It's a long project, and these two people are always very close to my heart," she said.

Her previous books focused on women and their place in Israeli society: "To the Unknown Sister: Holocaust Heroines in Israeli Society” and “Women in the State of Israel: The Early Years.” Geva developed a special relationship with Zivia Lubetkin, who was among the women she wrote about in her first book.

Geva explained her motivations behind taking on this new work, about two people whose lives are already commonly written about.

"For the Israeli public in general, at least during some periods of time, they were well-known figures, but with regards to the research, not enough was written and not on this scale,” she said.

“Also of importance in the creation of this book is the cataloguing of the Zuckerman archive in the Ghetto Fighters' House, which happened in recent years under the leadership of the archive's director, Anat Bratman-Elhalel. This gave me a very large amount of materials and historical sources that have not been studied before. These include diaries and memoirs, but what is really interesting are the more obscure sources: personal files, minutes of kibbutz meetings."

"Try to give as complete a picture as possible"

In addition to documents and certificates, Geva based her writing on recorded conversations she had with friends as well as with visitors, among them the poet Haim Guri, younger members of the youth movements in Warsaw, and kibbutz member and underground courier Havka Folman Raban, and others.

"Without a doubt, I had many, many sources – for these are public figures,” she explained. “But with regard to the more personal material, this is not always kept. Sometimes there is an official document, and then in the margins they write about it by hand – it is a kind of interpretation that comes from somewhere else, and it is necessary to put it in the context of the times."

Geva maintained that while she has love for Zivia and Antek, she tried to portray them in a way faithful to the reality, which sometines includes unflattering aspects.

“It's one of the gifts that you can give to such characters, because it turns them into well rounded characters, a man and a woman,” she said. “”No one is perfect. My goal was to reflect these personal concepts. The goal of a historical book, as opposed to heritage books, is to try to give as complete a picture as possible."

This article was translated from Hebrew by Rose Angela.