“My dominant experience, currently, is grief,” Jenny Sividia told Davar in an interview in November, six weeks after surviving the Nova rave massacre at which her brother, Shlomi Sividia, was murdered along with more than 360 other civilians. “It’s the trauma that’s guiding me now. Every action of mine currently revolves around having lost my brother.”

Sividia, 41, is an organizational psychologist, a doctoral student in gender studies at Bar-Ilan University, and the mother of two young children. The family lives in the city of Hadera in central Israel.

Since Oct. 7, Sividia has been wearing three separate hats: psychologist, grieving sister, and survivor. She spends her time at the Healing Place, a treatment center for survivors of the Nova massacre and families of victims, working to try to prevent the development of post-traumatic stress disorder in other survivors.

“People deal with trauma in different ways,” Sividia says. “I am discovering about myself that I am the type whose life gets turned upside down. My way to handle the fact that my brother isn’t alive is to manage my life according to the impact of what happened. Everything I was doing beforehand—what I researched, what workplaces I was seeking out—needs to change, so that I can tell myself, my brother wasn’t killed in vain. Only recently have I understood that that’s called post-traumatic growth. The trauma turns into organic waste that supports something’s growth.”

I met Sividia in November by a coffee cart in the central moshav of Herev Le'et, next to her younger daughter’s kindergarten. Friends and acquaintances who see Sividia stop to give her a hug and ask how she’s doing. “My story of survival is a story,” she says. “But mostly I want people to know that I had a brother, his name was Shlomi, I loved him, and he was murdered.”

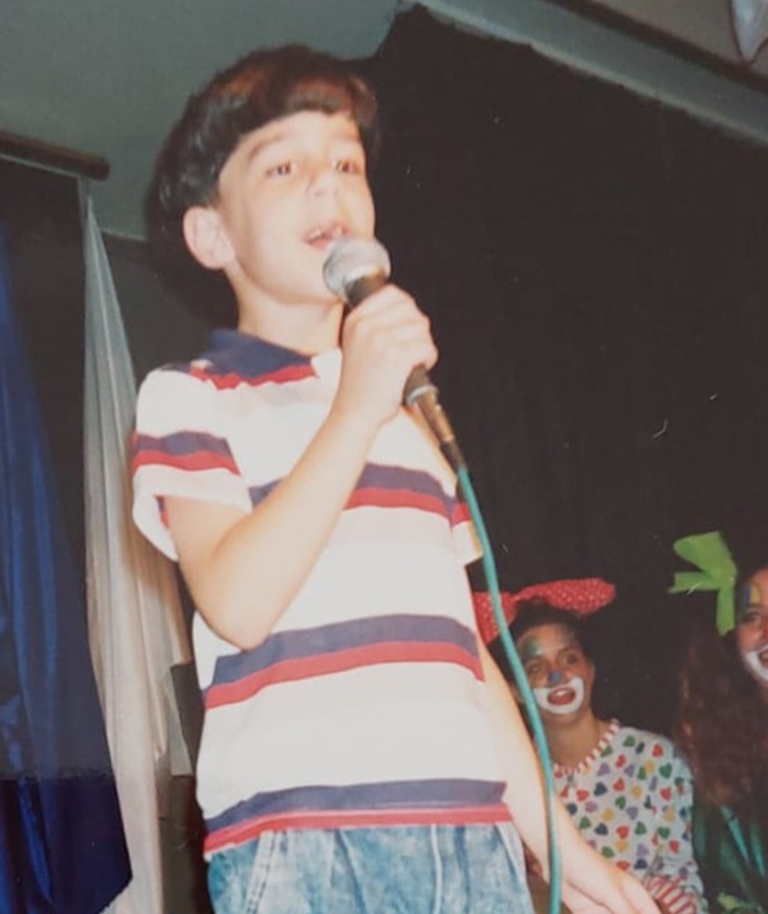

Shlomi predeceased Sividia, his only sister, as well as their two parents and his two children, both under 5 years old. He was 37 when he died. Shlomi was a high tech worker who put in 13 years at the same company. He loved humanity and, more than anything, music. “The musical notes flowed in his veins,” Sividia said of her brother. “He played guitar, he would sing, listen, perform, make playlists. He loved all genres, mainstream and underground. He knew artists that no one else knew, from Israel and abroad. And he really loved trance. He would go to parties for the music. He didn’t even dance, he just wanted to hear new tracks, like people going to a concert.”

“HaYehudim was one of his favorite bands. When we buried him, it was clear to us that music would be a meaningful part of the funeral, and HaYehudim came to sing at the funeral with [Israeli singer-songwriter] Rona Kenan. [Musician] Shai Tsabari came to sing at the gravestone unveiling.

“Shlomi’s life was music, and everything song reminds me of him. On his gravestone, we wrote, ‘He learned life, a man of love and giving, touched the hearts of many on his special path.’ And I didn’t understand how true that was until I met everyone from his life at the shiva. In the end, we decided to also carve the sentence, ‘Every song is an inescapable memory,’ from [Shlomo Artzi’s] song Fields of Irises.”

It’s quiet by the coffee cart. Birds are chirping calmly and the number of people around is unthreatening. Sividia takes a deep breath before starting to share her and her brother’s story:

“I had never previously been to an outdoor party. I had always wanted to, but life and parenthood led me to another place. I decided to buy tickets to Nova as a present for Noam [Lev-Ram], my partner of the last year, who was turning 45. Noam is really in the scene, and since we met we talked about going to a big one. I thought to myself, what’s better than planning a surprise and going together?

“I meant to find tickets for a party for the weekend of Oct. 20-21, the weekend of his birthday. I called Shlomi to ask about a party on those dates. He said that he hadn’t heard of one, but if he heard he would tell me. I kept looking, and somehow I heard about Nova. They said it was a great party, 4,500 people, the best production of the year, international, lots of recommendations. I decided to buy tickets. I didn’t update Shlomi.

“Noam and I got to the party on the night between Friday and Saturday, around 1:30 a.m. The party was just starting. The big stage was in the process of being put up, and everything had not quite started. There weren’t yet a lot of people there, and suddenly I saw someone who looked like Shlomi with a woman I didn’t recognize. I ran over to him. ‘Shlomi, no way, what are you doing here?’ He looked at me with a weird look and said, ‘But you said you were going on the 20th and 21st, why didn’t you say you bought tickets?’ So I met him and his girlfriend Lily for the first and last time. They had been going out only four months and that was the first time that someone from the family was meeting her.

“I wanted to rest, and we settled down at the big tent of ‘Good People’ [the volunteer organization associated with ELEM – Youth in Distress, an Israel group that supports at-risk youth]. Shlomi and Lily settled down next to us and we started talking. Lily asked me how Noam and I met. I told her and asked how they met. She laughed and said that they met on a dating app. Shlomi laughed and said that he felt bamboozled, because he had wrote in the preferences that he was looking for someone in the area of Rishon [in central Israel] and she is from Omer in the Negev and showed up on the app just because she had been working in the area.

“We spoke a bit. Shlomi was a bit disappointed that the event wasn’t organized enough and at such a late hour the big stage still hadn’t been put up. He compared it to the party he had been at on Rosh Hashanah, which had been better organized.

“And then one of the photographers of the event came. I called to him, and Noam and I posed for a picture. Shlomi told him, no thanks, but he still caught him in the frame, in the background. The picture was the last one, and it was uploaded later among the pictures of people who were at Nova. So there is, somehow, a photo of the four of us together, three hours before it all started.

“Later on, once they had also put up the second stage, Shlomi was really enjoying himself, I think. We didn’t manage to talk too much about how it was. We danced until the morning came. I really enjoyed the party and was really impressed by the community. There were incredible people and a really good atmosphere. Lots of beautiful people, smiling, looking at each other, dancing. People shared with each other, always offering food and drink. It was amazing. I thought that the atmosphere was just right for me.

“At 6:30 we started hearing booms. There wasn’t a siren. For the first seconds we thought they were fireworks. Before we lifted our heads, I told Noam, ‘How cool, they’re treating us to fireworks.’ And then I picked my head up and understood that they were Iron Dome interceptions.

“We’re Israeli. It’s all good, interceptions, we know what to do. Noam and I were good ‘old people,’ we lay down on the floor with our hands on our heads, but in the field there were all sorts of responses. At that stage there were a lot of people on drugs that were tripping and weren’t totally with us, and there were people freaking out, yelling, running around, filming. No one understood what was really happening.

“After a few minutes they turned off the music and yelled over the PA, ‘The party’s over, everyone here go home.’ I called Shlomi. He told me, ‘What a bummer, we just got to the car and now we need to go all the way back to get our stuff.’ I said, ‘Cool, go back to get the stuff and we’ll meet at the parking lot.’

“At the parking lot there were lots of people who couldn’t find their cars. There were those who really left their stuff and ran, left straightaway. In retrospect we know that the first to leave were kidnapped. Noam and I saw all the chaos at the exit. We didn’t yet know that there were terrorists, and we saw that the barrages weren’t ending, there were more and more. This wasn’t a regular barrage. We were afraid to get in the car, to wait in a traffic jam, that a rocket or shrapnel would fall on us. We decided to wait in the parking lot. Shlomi and Lily waited with us.

“We waited about 45 minutes. Around 7:15, the barrage had calmed down a bit. We had no idea that we were at the peak of the event, that terrorists had taken over villages and that there were terrorists on the road. Shlomi and Lily decided to go home. We didn’t have the patience to wait in a traffic jam, so we stayed. That’s where our paths diverged.

“They left, and a little while later we started hearing shots that sounded relatively far away, and there was a sort of muffled barrage. Around 7:45 I got a phone call from Shlomi. He said that they had nowhere to go, that they were stuck at a roadblock because there was a suspected terrorist infiltration. He said that they had left their car at the side of the road and ran to hide. He said, ‘We got really far from the cars.’ I said, ‘Good.’ It made sense with the fact that I was hearing gunshots. I thought, how many terrorists infiltrated, four? Five? Ten? There’s the army, there’s the police, they’re managing the event. We’ll wait here for a moment while it ends and we’ll go home. There was stress, but everything was under control.

“The shots still sounded far away, but they weren’t stopping. After about 15 minutes I sent Shlomi a text and asked if he had returned to his car yet. He said no, that they were still hiding. I assume that his car was left somewhere before highway 232, and he presumably went on foot to some shelter, because they found his phone in a shelter.

“Meanwhile we understood that the shots were already not so far away. People started shrieking, ‘There’s terrorists here, there’s terrorists here.’ Noam and I got in our Renault Kangoo and drove out of the main exit. We got about a kilometer away and got stuck. We saw lots of cars standing in place and people sitting outside of cars. It looked to us like some sort of demilitarized zone—there’s a war behind us, it’s being managed, and here it’s safe. We’ll stay here for a moment until they finish handling the event and we’ll continue home.

“We stopped the car and waited. I called my parents, and I remembered that neither of us hand told them that we were there. My dad told about a rocket that fell next to their house in Ganei Tikvah. I said anxiously that there were no sirens at all. Afterwards it turned out they had been texting with my brother, who said that he was at home in a safe room and unable to talk.

“As soon as I hung up, I heard Noam yell, they’re shooting at us. I suddenly saw a cloud of dust and people running toward us into the party grounds. I saw people running out from the party toward us, and the terrorists coming toward us, closing in on us.

“We turned around and went back into the party grounds. At this stage they were shooting people on the grounds, and we went in that direction. I heard people shrieking, ‘Let us out, they’re shooting us, get us out of here.’ Noam stopped every few meters and got someone into the car, and someone else, and another two, and another one. All together there were 13 people in our car.

“At some stage a woman got in who was shrieking, ‘My husband stayed behind, he didn’t manage to get in, I think they shot him. I have four kids. Get him out of here, so they don’t end up orphans.’ Another guy got in and yelled, ‘Take me to the hospital, they shot me in the hand.’ Everyone was hysterical. I turned around and said, ‘Guys, calm down. Everything will be okay. We’ll get you home and we’ll get you to the hospital.’

“We started driving and looking for how to get on the highway. We had no clue what was going on outside of the party grounds. The car was heavy, and terrorists were attacking us from everywhere. We tried to avoid holes, and at some stage we entered a forest. Somehow we succeeded to connect to highway 232.

“We had the option to turn left or right. In retrospect, I can say that it was right in the direction of [Kibbutz] Re’im or left in the direction of [Kibbutz] Be’eri. To the right we saw a totally open road, but full of smoke in the background. To the left we didn’t see much. We made the ‘illogical’ choice to turn left. In retrospect, that was the decision that saved our lives, because those who went in the other direction were just massacred.

“We came to a place where we couldn’t go forward because there were a lot of cars standing. We kept hearing shots and we decided to leave the car and to start fleeing on foot. We all got out of the car and started running. Suddenly I heard a boom and a blast and my ears were ringing. I didn’t stop. Noam shrieked, ‘An RPG fell here.’ We ran on the road, and we realized that wasn’t a good idea. We saw a dune, and next to it, some kind of thicket, and beyond that, a grove. We passed the dune and the thicket and kept running, bent down so that the thicket would hide us.

“We ran into the bombing, but at that stage I didn’t see or hear anything except for shots. I got into some sort of survival mode. Everything just disconnected except for what was helpful to my survival. I felt like an animal running away from a predator. Nothing could stop me. I didn’t see the corpses, I didn’t see the terrorists, I didn’t see anything that could shake me. In retrospect I know that we were really standing on corpses. I was there with shorts and a crop top, my whole belly was exposed. Only when I got home did I realize that I was full of cuts. At the time I didn’t feel anything.

“We found a giant thicket and decided to hide inside it. I started going in and I saw two figures from the direction of the plowed field. I asked Noam if they were guys from the party or terrorists, and I understood that there wasn’t much chance that partiers would come from there. It’s definitely terrorists. And we can’t hide here.

“We ran again. I don’t know how much, but I felt like it was kilometers. Luckily we were wearing sneakers. There were people there with heels, with flip-flops, barefoot. We can to a big bush with a lot of branches and leaves and there were a lot of people there. We hid there and we heard shots from everywhere. There was a picture there that I will never forget: in the bush, on the ground, there was a hole, really shaped like a grave. Someone small got in, covered herself with her coat, and looked like the ground.

“Noam was in Golani [infantry brigade]. He told me, ‘Improve your position.’ I told him, ‘There’s a woman there, I can’t lie on top of her.’ I tried to get in among the leaves without stepping on her. We were in the bush for about 15 minutes. The whole time there were shots and then quiet. Shots and quiet. People in the bush spoke, which was the most stressful. I was afraid that in the moments of quiet they would understand that we were hiding in the bush and shoot at us.

“In the bush, I opened my phone. The time was 8:44. I sent Shlomi a message, ‘Is everything okay?’ He wrote me, ‘Everything’s okay, where are you?’ I didn’t even see the ‘Where are you?’ I saw ‘Everything’s okay’ and I calmed down. I closed my phone.

“Suddenly we heard a yell, ‘Everyone who’s here, the terrorists are here. Run to the other side.’ We jumped out of the bush. We started running back. In retrospect I can say from people who were there that anyone who didn’t jump fast was shot there a minute after we left.

“Then I saw the first corpse that I remember. I recognized her because of the blue shirt of ‘Good people’ from the tent of ELEM – Youth in Distress. That I sat in. I stopped for a moment. I heard a man’s broken scream, ‘She was my student, I can’t believe it.’ Noam told me afterward that there were many corpses, but I only saw her. The moment I saw her I understood that this wasn’t an event that people get injured at and a second later our forces show up. I heard someone say, ‘Bro, put her in your car and we’ll save her.’ They answered, ‘I checked her, she’s dead. Run away.’

“We ran back to the car. All the time there were gunshots. We got to the car, we got in. Other people got in with us. And then someone put his head in the car and said to Noam, ‘Bro, what are you doing? They’re spraying the cars [with bullets]. Get out fast. Escape on foot.’ We got out of the car and ran. We heard shots and glass shattering. I looked back. They had sprayed the car with bullets.

“We got to a pomelo grove. Noam, me, and two other guys who had been with us in the car, Shalev and Hadar. We hid underneath one of the trees. I opened my phone. The time was 9:11. I sent two messages—one to my brother, I asked if everything was okay. He didn’t respond to that message. The second message was to my ex, the father of my daughters, who was with the girls. He has family in Be’eri and a good friend in [Kibbutz] Mefalsim, and I hoped that he wasn’t visiting either of them with the girls. I wrote, ‘Please tell me that you’re not in the [Gaza] envelope.’ He answered, ‘We’re not.’ At that moment a weight lifted from my heart. Like for a moment everything was okay.

“We were underneath a tree, a big tree that overflowed upwards with leaves and hid us. Shalev and Hadar sat bent over, Noam lay on his belly, I sat and lowered my head. I didn’t see what was going on around me. I just heard screams, and then shots, and then the screams stopped. Again screams, again shots, again the screams stopped. In between were screams of joy, Allah hu akbar, ya shabab, tael, tael.

“The shots got closer. I started to feel the blast, like the bullets were passing by my ear. I kept covering my eyes. Another blast, warm pieces fell on me. They were shooting explosives and also shoulder-launched missiles. The booms were from every direction and close to my ear. We couldn’t speak or move. Every so often I lifted my head and whispered to Noam, ‘Shlomi isn’t answering me, Shlomi isn’t answering me.’ Later on Noam told me that at that stage he was imagining his funeral. What people would say, what song they would sing, who would come, who would come to his house and start to organize his things. I don’t know why, but for me it was clear that I was getting out alive.

“We sat underneath the tree for close to five hours. It turned out that what Noam saw, and I didn’t, was that they entered the grove and shot the people in the trees. Two terrorists passed by our tree. There was a drone that they launched in order to track people, and it seems that the leaves of our tree were dense enough to hide us from above. Our tree, they missed.

“At a certain point I started smelling smoke. I realized that the grove was burning, and the fire was coming toward us. A few minutes passed and I heard the fire grazing the trees, and I started to feel the heat, and then the sparks too. We understood that we couldn’t stay in the tree, that we had to go. Through unbelievable luck, we suddenly heard, for the first time in those five hours, shouting in Hebrew.

“We left the tree and ran toward the shouting. We passed from row of trees to row of trees, and meanwhile we checked that the paths between them were empty. It was like that until we got to the last row of the grove. There we saw police forces on the highway next to a tank.

“We put our hands up and shouted, ‘We’re from the party, don’t shoot,’ so that they wouldn’t think we were terrorists. They gathered us around a tree where they were a few survivors who had made contact with the police. There were still shots, and the police offices shot back. The police officers, those heroes, put the tank and other armored vehicles they had there as a cover for us and they fought. Every so often they shouted to us, ‘Get down, lie down, put your hands on your heads.’

“Every few minutes a police car came to take us to the direction of the [Kibbutz] Urim gas station. After about half an hour, it was our turn. Noam and I got in a giant Toyota with an open trunk, with many other people. We started the drive, and in that stage I recognized the dimensions of the atrocity on the side of the road that we decided not to drive down.

“I saw many corpses—of civilians, of soldiers, of police officers. Corpses spilling out of the cars, corpses lying on the sides of roads. And most of all, I smelled—fire, smoke, blood, dust. At a certain moment I chose to close my eyes, and I covered them with my hand. A man sitting next to me said, ‘How can you close your eyes?’ I responded, ‘How can you not?’ Noam, who saw everything, told me that the rest of the way was even worse.

“We got to the gas station, and I needed to find Shlomi. That was all that mattered to me. We waited at the station, and a few minutes later, they came to bring us to the police station in Ofakim, which was already cleared of terrorists and became a sort of gathering place for survivors from the party. They also brought captured terrorists there. We sat there, and we saw that they were bringing in terrorists who had been shooting at us a moment before.

“In Ofakim I really started making phone calls, with 12% battery and no charger. There was someone who escaped with a charger and we took turns with it. I started updating all my friends, still not my parents. I sent a picture of Shlomi and asked them to publicize it everywhere, to start looking on lists of the injured, on lists of survivors who had gotten to lots of kibbutzim and gathering places. Meanwhile, I found myself asking people to tell me what had happened to them. I felt that it was my duty as a psychologist.

We met up with a woman who had been in the car with us, and a couple we had seen on the way, and Shalev and Hadar who were with us under the tree, and I was excited that they were okay. Every so often civilians came bringing their children to reserve duty and took survivors back home.

“I was sure that Shlomi was injured or hospitalized, or, worst of all, injured in the field and still undiscovered. I didn’t dare consider anything else. Every time someone went home, I said to Noam, ‘No, there’s no way I’m leaving here without Shlomi.’

“An hour passed, and another hour, and another hour, and there was still no information about him. I gathered all that I knew about Lily—she’s from Omer and she’s in her thirties. I uploaded a post to Facebook, and within an hour I found the phone number of her family. I called them, explained the situation to them, and we started a joint phone tree.

“Toward 5:00 p.m. a police officer entered and said that anyone who didn’t leave the station now would spend the night there, because there’s a curfew. I changed course and understood that soon my battery would die and I would have no way of searching for Shlomi. My head said to head home, my heart said no. But I decided to go home. The return was very complicated emotionally. I felt that I would get to my sofa and go to bed and abandon Shlomi.

“We went to my parents’ house in Ganei Tikvah and the search continued. In party clothes, with endless burns, cuts, and the sea of dust that was on me, I went with my dad to a control center that was established by Lahav 433 [the Israeli crime-fighting organization] in Lod, to look for Shlomi. When we got there I saw all the families. At first I asked them to show me pictures so that maybe I could identity them, but after six or seven that I didn’t recognize, I couldn’t anymore.

“The police officer questioned me, and I asked my father to leave. I wasn’t capable of telling my parents what had happened there. I gave all the details. Shlomi’s phone was still on, he just wasn’t answering. We called all the time. The next day, in the evening, someone answered the phone who explained that he was a volunteer who had found the telephone in a burned down bomb shelter.

“The gears started turning. It was already Sunday evening, the next day, and we were sure that that same night we would get a knock on the door [informing us of Shlomi’s death]. And we didn’t get one. And the gears started turning again—maybe he’s still alive, maybe his phone fell and he escaped.

“The next day, his telephone got to 433. We went to take it and saw that his phone was in one piece, without even a scratch. Just a few flecks of blood. I said, ‘Wait, his phone’s in one piece, there’s no indication that something terrible happened to Shlomi.’ The gears started turning again, maybe he's alive, maybe he managed to escape. I told my mom, ‘I’m his sister, I feel that he’s alive.’ And my mom said, ‘I’m his mother, I feel that he’s not.’ And I said, ‘Maybe he’s a hostage, but what’s better, dead or held hostage?’ And that’s how a very stupid conversation came to be.

“On Wednesday of that week they identified Lily’s body. Only then did I think that maybe Shlomi was dead. And on Friday we got the knock on the door. Six days after, relatively fast compared to many others. Two officers came. My mother passed out. And then there was the shiva, and the grave unveiling, and now there’s life afterwards.

“I really hoped that they shot him, that he wasn’t blown up, that he wasn’t burned, that he wasn’t injured and died of blood loss, or any other scenario involving suffering. I wanted to know that he had the fastest death involving the least suffering possible. This week we learned that he was shot in the heat. I breathed a sigh of relief, what luck, he died on the spot. That’s all we know so far. That he was shot in the head a few times, that there are no other marks on his body. We don’t know where, or when, we don’t know what happened to him until then.

“The first time I really understood that Shlomi was not alive was when the gravestone designer sent us the text that my mom and I wanted to have written on it. I saw the text all written out, mostly his name on top, in bold. It was the first boom—my brother is underneath the ground. I assume that there will be many others like that. The first year of mourning is full of firsts.

“On Sunday will be his first birthday without him, afterward the first holiday without him, his kids’ first birthdays without him, driving without him, vacation without him. I’m waiting for more realizations like this. And ever since I have the feeling that I’m alone in the world. It’s crazy and it’s really not true. I have a great partner, daughters, parents, a family, amazing friends. I am really not alone in the world. But he’s my only brother.

“I already understand that relationships aren’t necessarily for a lifetime. Things happen, friends switch out, people break out, at some point my parents will also pass away, I’m hoping between the ages of 100 and 120. But a brother is forever. It’s the only relationship in my life that I conceptualized as forever. It was supposed to be me and my brother against the world, beyond relationships, beyond the death of our parents in their old age, beyond relocations, beyond everything. That’s a hurdle that I think will be extremely difficult for me to get over. After the passage of almost two months, the adrenaline of survival has evaporated. The understanding that Shlomi is dead is only getting stronger.

“We were called after a couple—our grandpa and grandma, my dad’s parents. They moved to Israel from Turkey. My grandpa was called Solomon and my grandma was called Ojeny, and her nickname was Jenny. When I was born, it was decided that Ojeny wasn’t an option, but among Turks it’s a custom of respect to name children after the grandfather and grandmother when they’re still alive, so they decided it would be Jenny. When Shlomi was born, they decided to call him after grandpa’s Hebrew name, Shlomo. But nobody ever called him that. He was always Shlomi.

There were three and a half years between us, and it was always the two of us versus the world. Our parents, Eli and Aviva, worked hard, and we were latchkey kids. Basically since I was in second grade and he was in kindergarten, I would go home from school, pick him up from kindergarten. We would come home alone. The food was organized for us in containers and I had to heat them up, and then we would do homework together. That’s how we grew up together, a lot of two, with a very enveloping and inclusive parenteral structure, but a lot of time at home just him and me.

“He was always my little brother, the cutest and stickiest. My mom says that when I went with her on my Bat Mitzvah trip and he was at home with dad, he only wanted for Jenny to come home. We would have fights where we got on each other’s nerves, serious things. We had lots of things we didn’t agree about, but in the end, it didn’t matter how mad he got at me or me at him. If I needed something, Shlomi was always there. If he needed something, he knew that I was there for him. When I was pregnant with my youngest, I didn’t feel good and I needed to go to the emergency room. It’s most natural to call your mom, but I didn’t want to worry her, so I called Shlomi, who came without hesitation.

“He was stubborn, it messed with me. A man of principles. If he believed something he would stand for it, and not give up, no flexibility. From small things to big things. He would always argue with my mom about how she wanted to give them ice cream, and he said no, because they ate a lot of sugar. She insisted that it’s allowed at grandma and grandpa’s, and he just didn’t give up on his no on the ice creams.

“But there was a lot of giving and love between us. He was a person of love, a people magnet. He had many friends. He collected friends throughout all the periods of his life. Only at the shiva did we understand how many. Closer, less close, from so many circles—from high school, from the army, from the neighborhood, from work, fans of this band, fans of that band, people from the group of divorcees who play music, people from basketball. Relationships were very important to him.

“He would lose his temper at me that I didn’t tell him things. About half a year ago, he had a harsh conversation with me that he wasn’t willing for us to become ‘siblings only at holidays.’ He got mad at me that I didn’t call and I didn’t share things with him. Luckily, I listened to him, and for the past half year there was a lot more closeness. Our conversations were basically around romantic relationships, that neither of us really succeeded at throughout our lives. Maybe excluding my last go, and maybe what could have developed for him.

“From all the stories at the shiva, what most moved me was what a friend from work told. Only then did we discover that he learned Russian. No connection to his ancestry. He had older Russian neighbors in the building and he wanted to communicate with them and to figure out if they needed help. That’s the person who he was.

“He was also an incredible father. His time with his kids was always sacred, and you couldn’t bother him when he was with them. Now I think that maybe it’s lucky that his kids are small. There are some who will say that it’s an advantage that it happened at a young age, but I don’t know. The younger one goes around a lot saying, ‘Do you know that my dad died? Dad died, dad died,’ like some sort of mantra. On the other hand, I am not capable of thinking of the possibility that my nephews won’t remember that Shlomi was their dad.

“I think a lot about my parents. I admire them. They only had two children, both of whom were at the party. One was murdered, one survived. I don’t know how they are managing to contain the complexity of the relief and the joy of the one’s survival and the weight and pain of the other’s loss.

“At the beginning, I had a lot of shame. Like I said, my brother was stubborn. He said he was heading home now. I didn’t argue with him, I knew there was no point. But if I had only convinced him to stay, told him to wait, if he were to have stayed with me, maybe he would still be alive. I told this to my mom, and my mom looked at me and said, ‘Either you would both be alive or you would both be dead.’ Since then I’ve been trying to get rid of that shame.

“I think that now I’m into scripture—this is what happened, this is fate. I was there at the party for my first time, he was there and we met by chance. Seems like I needed to say goodbye to him. That’s what needed to happen. We need to deal with that. He was martyred. His soul is ascending to the highest realm without a lot of suffering. I think that if you’re going to die, it’s a pretty good deal. At least for him. A little bit less so for us.

“When Noam and I spoke on the phone at night before sleep, he would also close with ‘golden dreams.’ Since they told us that they found the body, he tells me, ‘May Shlomi come to you in a dream.’ That’s the official send-off. I put a picture of him next to my bed to encourage it.

“I am trying to engage with telling the story, that people will hear that there was a Shlomi. His friend who worked at [the Israeli branch of the American company ServiceNow] did a few projects. They collected laptops and distributed to children who were evacuated from the [Gaza] envelope with the idea of doing it in Shlomi’s memory. They’re also making a music room and a scholarship in his name.

“I have a lot of thoughts about how to commemorate him. Maybe to create a fund that supports upcoming musicians. I find myself writing many passages to him, speaking to him. As a first step, I got a tattoo. At the shiva one of his good friends approached me and told me that he wanted to get a tattoo and he was considering three lines from three different songs. I understood that I need to pick one of them and get it in his memory. I chose ‘Only love exists among the ruins,’ from the song Within the Pipes by [the Israeli band] Algier. In the end, I decided to get rid of the ‘only.’ Among the ruins where the two of us were, there was not just love. There is also hope.”