For Randy Schoenberg, a lawyer from Los Angeles, Oct. 7 was supposed to be a holiday. He was in a hotel in Tel Aviv preparing for the first screening of his movie “Fioretta,” a documentary about family history that tells about Schoenberg’s travels to Italy with his son to learn about their family history. But before the film’s Israeli debut on Oct. 8, Hamas attacked Israel, setting off the Swords of Iron war.

“On Saturday morning we were still asleep in our hotel in Tel Aviv,” Schoenberg told Davar in an interview from his home in Los Angeles. “And then the sirens started. Obviously I didn’t know what was happening, and I called to ask the Israelis I know. By the evening, I knew that the debut would not take place.”

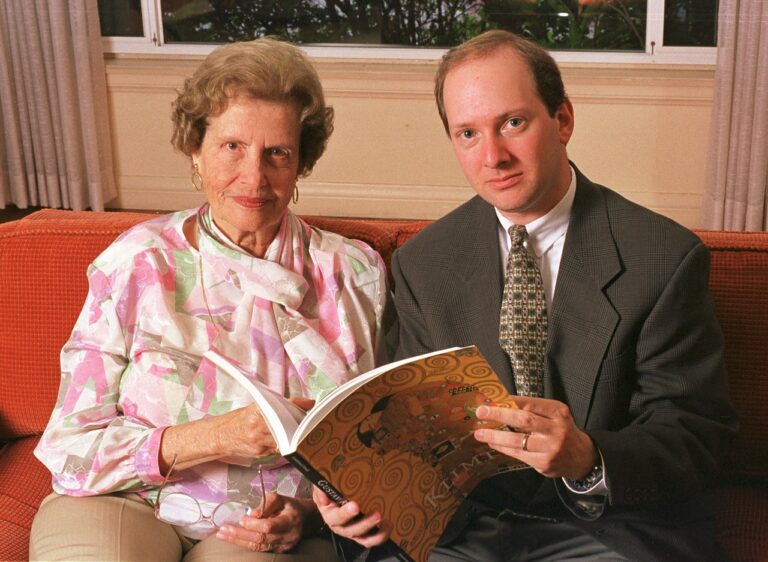

If the name Schoenberg sounds familiar to you, you may have seen the 2015 movie “Woman in Gold,” a fictionalized version of the young Schoenberg’s real-life attempt to reunite Holocaust survivor Maria Altmann with five Gustav Klimt paintings that were stolen from her family by Nazis during World War II.

After a seven-year legal struggle, Schoenberg succeeded in his case against the Austrian authorities, forcing them to return the stolen paintings.

Schoenberg used the legal fees he earned in the case to take on philanthropy and work for the public, including serving as president of the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust. He also devoted himself more seriously to his long-time hobby of genealogical research.

“At age 8 I started researching my family roots, and since then I haven’t stopped,” Schoenberg said. “My family tree grew and grew without stopping. During the coronavirus, I visited my cousin Serena, who is an artist and filmmaker, and I told her that I can draw a single line from our generation to the start of our family 500 years ago. So, she proposed that maybe I make a movie about that.”

Schoenberg returned home and met up with a friend in Los Angeles who introduced him to the Israeli American director Matthew Mishory. “I showed him the idea for the movie,” Schoenberg said. “Matthew’s family is from Eastern Europe and came from a different mentality. He was very skeptical about the cooperation we would receive from the Europeans, but he was very interested in my optimism and he agreed to take on the task.”

At a certain stage, Schoenberg’s son Joey, who was 18 at the time, joined the project as well. “His joining introduced an additional layer that was an intergenerational journey of a father and his son. We’re on good terms. He’s my third son. He wants to be a chef and is interested in clothes and definitely not in family history. It was very interesting to introduce him and to show him that there are other things in the world besides him and besides the present he’s living in.”

“It wasn’t easy to interest him in the topic,” Schoenberg continued. “He’s young, and he’s interested in young people’s things, and some of the time he was bored during filming. But the bottom line is, he enjoyed both being part of making a film and the discoveries we made. It’s sort of like the broad audience that will watch the film—you need to find the shared point of interest and ways to introduce it into the story.”

In a gentle and engaging way, the film shows the connection between Schoenberg’s passion for discovering his family roots and his distance from his son, who enjoyed the opportunity to travel to Europe and wondered what tattoo to get.

“This is the practical expression of the act of searching for one’s roots and passing on that knowledge to the next generation,” Schoenberg said. Throughout the movie, Schoenberg and his son visit graveyards and encounter family members who were kings, mystics, false prophets, and regular people lost to time. These relatives are witnesses to Europe’s past, distant and recent—expulsion of Jews, the Holocaust, communism, and the refugee crisis brought on by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“‘Fioretta’ is a universal story,” Schoenberg said. “Everyone wants to know where they came from. It’s a treasure hunt, after 500 years of Judaism filled with ups and downs, and there are many things that were forgotten, which adds to the importance.”

“The Holocaust has an enormous place in Jewish history, but everyone imagines the Jew like Tevye the dairyman from ‘Fiddler on the Roof.’ But on our journey, we also found a different Judaism, one that’s established, communities that had cultural life and developed science and were integrated into the countries where they lived,” he continued.

Schoenberg grew up in a Reform Jewish household, but he’s been exposed to different types of Judaism throughout his life. “Jews love thinking that they’re different from each other, but they’re really similar, even though everyone thinks that their practice is correct,” he said. “My Hebrew is not so good, but as I continue to read and research more about Jewish history, I’m finding out how similar we are, despite the existence of Ashkenazis and Mizrachis, Reform and Orthodox. Everyone is established on one Torah with different leaders.”

“In the movie we tried to bring tangible things, Jewish objects, documents, certificates, cemeteries, that can illustrate Judaism,” he continued. “In contrast to American cemeteries, lots of time, money, and thought were devoted to European cemeteries. Cemeteries in Europe show in a very lively way the figures that are buried there, and through them you can see the great diversity of people who lived in those communities.”

Months after its intended screening, “Fioretta” premiered in Tel Aviv at ANU: The Museum of the Jewish People last month. Schoenberg is a donor to the museum and is also working with ANU in the development of an app that will allow users to discover their family history and connections to famous Jews.

“Visitors will be able to enter their name and find out within seconds how closely related they are to other visitors to the museum. It turns out that in the end, we’re all connected, and the question is just through which family ties and what’s the distance between the branches of the tree,” Schoenberg explained.