This March, Alex Dancyg, a 76-year-old historian, educator, farmer, and one of the pioneers of the program to send Israeli high-schoolers on trips to Poland to commemorate the Holocaust, was awarded the Jan Karski Eagle Award for service to humanity. This award, created by and named for a fighter in the Polish underground who revealed the horrors of the Holocaust to the Allied nations in real time, was presented to Dancyg in an emotional ceremony in Warsaw. The only thing missing was Dancyg himself, who has been held captive by Hamas in Gaza for 219 days.

“It’s difficult not to notice the spiritual parallels between the namesake and the recipient of this award,” Father Alfred Wierzbicki, the representative of the Jan Karski Educational Foundation in Poland, said in his speech. “They are both people who are able to expand their identities. In the face of the Holocaust, through which, he stated, humanity committed the original sin for the second time, Jan Karski himself became a Jew by choice. Similarly, Alex Dancyg is a Jew who has always served his people and the State of Israel, but never stopped being Polish. He is receiving this award for fostering a collaboration that has changed reality, and for extraordinary achievements in the field of history education. This award is an expression of our gratitude for creating so many sites of friendship and connection, which, although they come from different ideological traditions, all believe in the reality of a better world.”

In his speech, Wierzbicki spoke about Dancyg’s kidnapping. “Alex was among the group of Jews who were abducted from Kibbutz Nir Oz, and fell victim to the violence that he always strongly opposed. He is a man of peace, dialogue, and friendship,” he said, adding, “Alex, my dear friend, I look forward to your return to Lublin. We’ll eat some aspic [a Polish dish similar to a savory jelly], we will laugh and wonder how we can improve the world at least a little.”

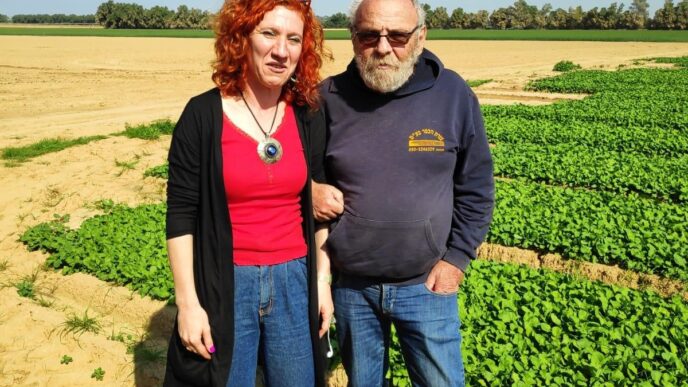

Wierzbicki has been in close contact with Dancyg ever since he attended a seminar run by Dancyg at Yad Vashem almost 20 years ago. In his work at Yad Vashem, Dancyg created professional seminars for non-Jewish teachers, especially from Poland, who studied the Holocaust. As part of the seminars, they learned about the Holocaust and traveled around the country, and Dancyg would continue to visit the teachers and meet with their students after the seminars ended. Dancyg never stopped meeting with students and teachers, even after he retired in 2018. He had just returned from a trip to Poland a week before he was kidnapped on October 7th.

Wierzbicki is not Dancyg’s only Polish friend. As Dancyg’s son Yuval accepted the award on his father’s behalf, the audience was filled with dozens of Danzig's friends from all over Poland, some who had traveled as far as 400 kilometers (250 miles) to be present. After he was kidnapped, a special group was formed in Poland to fight for his release, including teachers, clerics and intellectuals, journalists and cultural figures. Some knew him personally and some didn't, but all testify that Danzig had touched their lives. Among other things, together with his family and friends in Israel, they operate an international Facebook page for his release, raise awareness in Poland about him and the other Israeli hostages, organize meetings with government representatives and public figures, write articles for the media and organize press conferences and demonstrations.

“Alex has touched many people, even those who don’t know him personally,” said Orit Margaliot, a former colleague of Dancyg at Yad Vashem’s Poland desk who became one of his closest friends during their years working together. “He believes strongly in Israeli-Polish dialogue, and has been involved in it for his entire life. More than 2,500 Poles have attended seminars that we ran. Teachers, museum staff, politicians, mayors and heads of government agencies, priests and other clergy and many others. Many of our Polish partners became active in Holocaust education after our seminars, and suddenly their eyes were opened,” she said. “He continued to travel independently even after he retired. He was in Krakow and in Warsaw recently, participating in a conference on Jewish culture in Kazimierz [the historically Jewish district of Krakow]. I am organizing an instructor training course in Warsaw in June. I know that if he were here, he would ask to be a part of it.

“When Alex was taken hostage, the news spread through Poland very quickly,” Margaliot said. “There was a time when there were a lot of articles about him, and even today whenever an article is written about him it spreads there as well. He made a lot of waves there. On Facebook there are a lot of videos of Poles talking about him, some of them famous. On the night of the Seder on the first night of Passover, I posted about his 200 days in captivity with a picture of the empty chair we set out for him, and one of my Polish friends wrote a very moving response. It’s like that all the time. The director of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum wrote to me not long ago and asked if there was any news.”

“His Story Moves A Lot of People Here”

Dancyg was born in Warsaw in 1948 and immigrated to Israel at age 9 with his parents, both Holocaust survivors, and his sister. He joined the Socialist-Zionist youth movement HaShomer HaTzair and later moved to Kibbutz Nir Oz with his partners from the movement. He started a family there and had four children, and lived on the kibbutz until he was taken hostage on October 7th. As much as he is an Israeli and a Zionist, Dancyg has always remained connected to his Polish heritage. He speaks fluent Polish, is well-versed in past and present Polish culture, and loves Polish sports, literature, and poetry. He often visited Poland, both in connection to his life’s work, education about the memory of the Holocaust, and to visit friends in his second homeland.

“He is also a role model for Poles, his story moves a lot of people here. As far as people here are concerned, a Pole was taken hostage,” said Marta Rebzda, a journalist, writer, and radio personality from Warsaw and a member of the group of Poles campaigning on Dancyg’s behalf.

The group was convened by Dorota Kozarzewska, a Polish tour guide who works in Africa and one of Dancyg’s friends. “She called and said she was coming back to Poland from Africa to gather Alex’s friends to try to create pressure and promote his release,” Rebzda said. Thus, the group of journalists, teachers, clerics, and artists working on his behalf was created.”

“It happened very quickly, about a week after his abduction,” adds Adam Moschau, an educator and lecturer in Polish history, Polish Jewry, and the Holocaust and a friend of Dancyg’s from Krakow. “In the first few days we were shocked. We didn’t know what we were supposed to do. We kept in touch with Orit Margaliot, but we didn’t really understand the situation. We needed someone like Dorota to hold us together, but we knew that we had a role to play.” Among the members of the group, besides Kozarzewska, Rebzda, and Moschau, are actress Dorota Salamon, journalist Anna Mariola Rożanska and educator Janusz Berdzik.

“The idea was to use everything we have to make as much of an impact as we possibly could. Connections in the media, in government, whatever is possible to continue to raise awareness and knock on doors,” said Moschau.

“We try to create as much publicity about Alex, however we can,” Rebzda added. “Articles in the press, information on television, the radio, social media. We set up the Facebook page together with Orit, there were articles in all the major Polish newspapers, and there are new ones published from time to time.” Dancyg’s friends in Warsaw contacted TVN, one of Poland’s largest channels, and they broadcast a major television report that included pictures from Dancyg’s home in Nir Oz. The group also got in touch with Yuval Dancyg, Alex’s son. “He was in Warsaw several times, and we arranged meetings with the press and politicians. It was important to us that Yuval meet as many people as possible.”

Dariusz Paczkowski, an artist with no personal connection to Dancyg, created graffiti with Dancyg’s face with a statement calling for the release of the hostages which has since been spray painted all across Warsaw. Public figures, including the director of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum Dr. Piotr Cywiński, the journalist Grzegorz Gauden, the poet Witold Dombrowski, the actor Włodzimierz Press and more from across the country filmed short videos about Alex and called for his release. “He told me that in his youth he was in love with Alex's older sister,” Rebzda said of Press with a smile, amazed by Dancyg’s impact in all sectors of society. “In the video, he said he’s never met Alex in person, but hopes for his release.”

“He Disagrees Passionately, But He Knows How to Conduct Dialogue”

Rebzda met Danzig at the beginning of her career on Polish radio almost 15 years ago, in November 2010. She broadcast a documentary program on Polish radio about dealing with multiple identities, which later became very famous. When she happened to read an article about Dancyg, she immediately recognized that he would be a perfect guest for her show. “I read about Alex in a Polish newspaper, about his activities and the dialogue that he encourages about the Holocaust and the Jews in Poland. I wrote to him, and he responded almost immediately in the affirmative. We spoke on Skype and agreed to meet. We met in March 2011, when he came to Warsaw, and we recorded the show.

“He spoke about his Polish, Jewish, and Israeli identities, and how they connect to each other. The recording we made was very long. Something like three hours. He was so fascinating. We met and recorded again, that's how it started. He was actually the starting point of my career.”

Moschau also met Dancyg around the same time, when he was a high school history teacher. Even before attending a seminar at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, he was active in Holocaust remembrance education, conducting his postdoctoral research on the subject. “I came to the seminar, and Alex gave some of the lessons, in Polish. During the seminar he slept with us in the hotel, because he lives far away, and we would meet in the evenings as well. My impression of him was that he was a typical leftist-socialist sabra [native-born Israeli], kind of tough and straightforward. I thought that he thought I was some kind of European intellectual snob. He kept his distance.

"Suddenly, one evening he asked me: ‘Do you know who scored the first goal for the Polish national football team? Yes, I replied. Leon Sperling [a Polish Jewish footballer from Krakow who perished in the Holocaust] got the penalty, Josef Klotz [also a Jewish player from Krakow who perished in the Holocaust] scored. It was on May 28, 1922, in the 27th minute, a kick from the left wing to the center.” It was Poland's third game ever, against Sweden, and its first victory. “He was impressed, and so we started talking more.” Since then, Dancyg and Moschau have become friends and met many more times, both in Poland and in Israel. Moschau even visited Dancyg at his home in Nir Oz several times. During his visit to Poland last September, Dancyg met with Moschau and Rebzda. It was their last meeting before he was taken hostage.

Margaliot also testified to Dancyg’s significance in her life. They met almost 25 years ago, when Margaliot took the instructors' course at Yad Vashem. “I’m almost 100% Polish, from a very anti-Polish family unlike him, who loved Polishness. I wanted to leave his lecture in the middle, because I was so angry. We had a lot of friction. But since 2006, when we worked together at the Poland desk, it became a deep friendship. We talked almost every day, and he's one of my closest friends," she said.

“Alex is one of the most educated people I know, and he's a bridge, whether between Jewish Israelis and Poles, or within Israeli society. He may very well disagree with many things, and he disagrees passionately, but he knows how to talk. It was important to him, he always had friends of all kinds. In some ways we really are opposites. I'm 30 years younger than him, I'm a religious Jerusalemite who comes from a right-wing home. There would seem to be no reason for a kibbutznik from HaShomer HaTzair who’s old enough to be my father to connect with me. But it worked. Even though over the years we've clashed on many things, Alex always tells me that I'm his most successful student.”

Moschau and Rebzda said that on October 7 they had already begun to worry about Dancyg. “I have a Jewish relative who lives in the United States,” said Rebzda. “She wrote to me on Saturday morning, around 11:00, that something was happening in Israel. I was in Krakow at the radio awards ceremony at the time, and I wrote to Alex immediately, asking where he was and if he was okay.”

Danzig never responded to the message. “In the afternoon I called Robert Zuchta, one of the most important pioneers of Holocaust education in Poland and a very close friend of Alex's. He didn't know anything, and we started to get nervous. We talked to Orit, and that's how we found out.”

“In the morning, a friend from Ukraine called me and asked if I had seen what was happening in Israel,” Moschau said. “I turned on the TV and saw what was happening on the news. I recognized the area from the times I was in Nir Oz, and I wrote to Alex. He didn't answer me, and I saw that he wasn't even connected. Rumors started circulating in Poland about his abduction, but only later did Orit confirm to us that that’s what happened.”

Margaliot, who observes Shabbat, was also updated only in the evening. “I was at my sister's house on Kibbutz Kfar Etzion. The phone was off on Saturday. My nephew was called up from the reserves at 8:15 in the morning, and they went through all the houses in the kibbutz and told them to turn on their phones. We hadn't really realized what was going on yet. It wasn't until Saturday night that I did what I always do when something happens in the Gaza envelope, and I called Alex. He didn't answer, and I sent him a WhatsApp message. Only then did I notice that he had last been online at 9:30 a.m. I've had [his son] Matti’s phone number since Alex’s heart attack four years ago. Matti wrote to me: ‘There’s been a disaster here, I don't know where my father is, the situation is not good. I got a million messages from Poland. All throughout Shabbat. It was really crazy.’”

“He Felt that Both of His Countries Were Falling Apart”

Diplomatic relations between Israel and Poland have been rocky over the last several years, with conflict arising over supervision of the curriculum of Israeli student trips to Poland, among other issues. Dancyg has been very critical of the policies of both countries. “He was very frustrated with everything that was happening in Israel, and also with what was happening in Poland, especially with the government's attitude toward the Holocaust and history,” Rebzda said. “He really felt that both of his countries were falling apart.”

Dancyg, who had long hoped for a change of government in Poland, had already been taken hostage when it finally happened after the 2023 elections. “I'd be so happy to tell him about it,” Rebzda said. “I know it would make him very happy. We have been in a different situation since the elections. As for Israel, he seems to have good reason to be pessimistic.”

Moschau said that many teachers, especially those active in Holocaust remembrance education, continued to work and teach throughout the eight years of conservative rule in Poland against the wishes of the government, which denied Polish involvement in the Holocaust. “The fact that we had a friend there, Alex, who continued to come and visit, even though he was retired, who attended the official and unofficial meetings, was a huge support. We have continued to operate even without him and the meetings have been very uplifting thanks to what he created.”

“He was so genuine, even when what he said was controversial,” Rebzda added. “He wasn't trying to please anyone. That's an important thing I admire about Alex. His ability to communicate with people regardless of their age, education or worldview. He’s a person who’s easy to communicate with, who breaks down obstacles between people and builds bridges. That's his strength, and that's why he succeeds in creating a dialogue between Poles and Israelis.”

“The relationship with the government was problematic,” said Margaliot, “but Alex was very angry about the fact that in Israel they talked and wrote about ‘the Poles.’ Up close, we saw that there is the government and there are the people. We saw our friends in Poland fired from their jobs because they wouldn't toe the line, because they fought for Polish Jewish heritage and Polish Jewish memory. We saw them not giving up and continuing to fight. Our friendship with our partners in Poland was greatly strengthened throughout the previous government there and around the struggle for the truth. Even now, Poland and the Czech Republic are the safest countries for Jews today. And in Poland at least, I think that definitely has something to do with the connections Alex made. There were many rallies in support of the hostages, there were many important people who spoke for us. And those connections are all thanks to Alex.”

In the midst of all the hard work, despite the dialogue and cooperation that Dancyg promoted and despite the relative security it allows Jews today, the atmosphere in Poland is still tense. "Dorota and I participated in a podcast. We talked about Alex, what he does and why he's important," Rebzda said. “There were all kinds of reactions to it, and some of them were nasty and vicious.”

Moschau adds that there is a lot of antisemitic and anti-Israel activity in Poland today. “Part of this is led by Polish nationalist leaders who are seizing an opportunity to gain power. And there are, of course, pro-Palestinians on the left. There are ignorant people on both sides who don't understand anything. There are also liberals who criticize the Israeli government and the way it is dealing with the war, while at the same time showing sympathy and compassion for the Israeli victims, and there are also diehard supporters of Israel on all sides.”

Moschau, who teaches history students about Jewish sites in Krakow and its ghetto in his course, says the university fears that the course will not open next year because students may not enroll. “No matter what they think about Israel or the Israeli government, this story is about Poland. These people were Polish citizens, Polish Jewry was a significant part of Poland's history for hundreds of years until they were murdered. As an educator on the subject of the Holocaust, I find this absurd and ridiculous. But there's definitely that kind of atmosphere.”

Even following Dancyg's approach, he stresses, it is impossible to learn about the Holocaust without knowing Polish culture and history. “Jews didn’t appear in Poland out of nowhere as victims of genocide. They lived there and their culture flourished there for centuries. You have to know this culture. But we must also know the Polish culture in which Jewish culture developed. Alex would ask: ‘When you visit Paris, do you go to Notre Dame Cathedral? Obviously. So why when you visit Krakow is it not obvious that you will visit Wawel Castle in Krakow?’ Thirty years ago, this idea was revolutionary in Israel.”

“He Will Continue to Teach Us”

Dancyg, who underwent heart surgery several years ago and regularly requires medication, sent regards to his family with the hostages who were released in November. They said he was being held in a tunnel and wasn't getting the medication he needed. Since then, there have been no signs of life from him. His brother-in-law, Itzik Elgart, is also still being held in Gaza.

“I feel the tension between realism and optimism,” admitted Moschau. “The realistic part of me is saying, ‘he's 76 years old, he has heart problems, he's been there for six months. Is he getting his medication? I don't know.’ On the other hand, since there hasn’t been any news, I continue to believe.”

“Me too,” Rebzda said through tears. “Especially because I feel a strong connection with Alex. We have always been in touch throughout the years. I still feel the connection and I feel him thinking of me. I catch myself at different times throughout the day feeling the connection with Alex. Still. That's why I believe he's still alive. I miss him very much. He was and still is a teacher of life for me, and I hope he will continue to be.”

This article was translated from Hebrew by Paul Weissfellner.