“As a result of Menachem Begin’s peace plan, Israel finds itself in a situation reminiscent of the saying ‘damned if you do, damned if you don’t.’ Because on the one hand, its rejection by America and Egypt would force us into a political bind, but on the other hand, its acceptance is nothing less than a national disaster."

– Yigal Allon July 1979

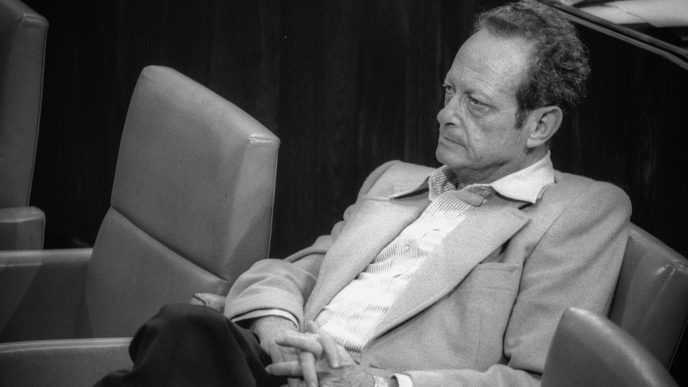

Why did Yigal Allon, who led the elite Palmach forces throughout Israel’s War of Independence and served as a leading political figure of the Israeli left in the 1960s and ‘70s, see Israel’s groundbreaking peace agreement with Egypt as a national disaster?

How was he able to identify, within the emerging agreement, the seed of the calamity which came to fruition on October 7, 2023?

Forty-five years after that agreement, and more than seven months into Israel’s war against Hamas in Gaza, the complex connection between the two must be unraveled in order to understand events as they unfold and in order to shape a different future.

***

Yigal Allon harshly criticized the policy of the Israeli government led by Menachem Begin in shaping the peace agreement with Egypt. Allon observed reality through the conceptual lens of "defensible borders," and with his keen perception he was able to identify a fundamental flaw in the political plan that was being forged between Israel, Egypt and the United States: the creation of an unlivable reality in the Gaza Strip, a reality which would inevitably lead to bitter conflict and acute tension that would only fester as the years went by.

Two central factors contributed to Allon's grim outlook on the peace plan. The first was the exclusion of Jordan from the agreement, an expression of its broader failure to resolve the Palestinian issue. The second was the creation of conditions in the Gaza Strip that would most likely produce a political impasse, and as a result, extremism, violence and endless conflict.

The peace agreement signed in March 1979 stipulated that the Sinai Peninsula, which Israel had seized from Egypt during the Six-Day War in 1967, would be evacuated and returned entirely to Egypt. After a five-year intermediary period that would include negotiations and normalization of Egyptian-Israeli relations, a complementary process would begin with the aim of resolving the status of the Palestinans. This supplementary process was given the conspicuously vague and non-binding title of: 'The Autonomy Plan.'

Without Jordanian involvement and agreement, Allon argued, such a plan would be at best pointless, and at worst dangerous for Israel, as it would only reduce the possibility of a solution to the Palestinian issue. Perhaps that is exactly what the Prime Minister was aiming for. But Allon, unlike Begin, was not distracted by short-term political gains, and was beholden neither to establishment power brokers, like Foreign Minister Moshe Dayan, nor new players on the scene, such as Gush Emunim, a new movement at the time that was dedicated to establishing Jewish settlements in the West Bank, Gaza Strip and Golan Heights. Allon opposed any move that would resolve the conflict on one front without addressing the bigger picture, especially when Israel stood to lose significant assets.

It was clear to Allon that by failing to take the initiative and promote a coherent policy on the Palestinian issue, the Israeli government was abandoning the arena to other players to shape it as they wished. Among these players was Gush Emunim, which at the same time began to operate in the West Bank and established settlements which Allon described as "display settlements, in the wrong places, at the wrong time and with a method bordering on scandal." He believed that time was not on Israel’s side, and that it was the government’s duty to proactively shape both the physical landscape and the relations among the peoples living between the river and the sea. To Allon, the inherent combustibility that hung over the Gaza Strip from the day of the Israeli evacuation of the Sinai was clear, predictable and dangerous.

He understood that the Gaza issue had to be settled one way or another, and considered it unthinkable to exempt both the Egyptians and the Jordanians from any responsibility over the territory. Egypt and Jordan were presumably surprised by the Israeli generosity on the matter and made sure not to miss the chance to extricate themselves from liability for such a dense and complex region. In the aftermath of the peace agreement with Egypt, Israel found itself solely responsible for a territory that was too small to stand on its own and too crowded and underdeveloped to think that agitation, extremism and violence would not entrench themselves there over time.

Allon saw it as a missed opportunity. In his view, the agreement turned Gaza into an intractable problem rather than making it part of the solution. In the face of the new reality of the Middle East after the Six-Day War, Allon had formulated a proposal to stabilize geopolitical relations in the region. While it was never adopted in an official capacity, the Allon Plan, and in particular its focus on defensible borders, was one of the single greatest influences on Israeli policy in the 1960s and ‘70s. In the plan, the Gaza Strip was assigned a key role. Allon believed that it would be one of the most prominent assets that Jordan would stand to benefit from if it accepted responsibility for the Palestinian population on both sides of the Jordan River. In his 1979 essay “Peace Through Security,” Allon wrote:

“A Jordanian-Palestinian port in Gaza could transform Amman into an international, land-sea transportation hub in the heart of the Arab world. […] A port developed in Gaza could serve as a gateway to the Mediterranean Sea, the Black Sea, and the Atlantic Ocean. […] A land bridge for heavy trucks or a railroad, which would pass through Israeli territory, would make it possible to make Transjordan a transportation junction – in cooperation with Israel – that would enrich the Jordanian-Palestinian federation and strengthen its position in the Arab world. […] Jordan and the sane elements among the Palestinians have an objective interest in finding a political solution. The formation of an ideologically extreme Palestinian entity in the occupied territories and the breakdown of the peace process between Egypt and Israel are liable to exacerbate the atmosphere and encourage militant, religious, nationalist radicalism in a social guise, which is not in the best interest of the Hashemite regime or of the vast majority of the Arab population on either bank of the Jordan River.” [Emphasis added]

Only by explicitly stating the name 'Hamas' could Allon’s prediction have been more exact. He understood that conceding the Rafah Plain region, the natural geographical extension of the Gaza Strip, to Egypt would leave the Strip too isolated and narrow to accommodate its future population. No less importantly, he understood that such a concession would also weaken Israel's ability to establish a defensible border around the Strip, especially if the area within that border came to be dominated, as he predicted, by "militant, religious, nationalist radicalism in a social guise."

The Logic of Gush Katif

As far back as the Israeli War of Independence, Allon had identified Gaza as an area of concern. As the commander of the southern front in Operation Horev, a large-scale offensive against the Egyptian army in December 1948, he led the IDF beyond the lines of the partition plan and attempted to establish a new Israeli-Egyptian border. His goal was to expand the Gaza Strip southwest, beyond the Rafah Plain region and up to the Egyptian city of el-Arish, and to thereby provide Israel with "strategic depth and borders of strategic topographical value."

For political reasons, Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion cut the operation short and ordered Allon to urgently return to within recognized international boundaries. His many protestations, which even included a direct flight from the battlefront for a face-to-face meeting with the Prime Minister and the Minister of Defense, did him no good. To his dismay, he withdrew his forces back to the Israeli-Egyptian border, the same one that separates the two countries today. All the while, Allon was convinced that this border was not sustainable and would lead to disaster in the future.

Indeed, throughout the following years, the region suffered from instability. There were numerous incidents of violence, most notably the 1956 murder of Ro’i Rothberg at Kibbutz Nahal Oz. But in 1967, with the outbreak of the Six-Day War and the Israeli seizure of the Sinai Peninsula, Allon’s vision of secure borders for the State of Israel seemed within reach. "Only now," he wrote, "close to twenty years after the establishment of the State, when our army is standing on the Jordan and near the Suez Canal and on the Syrian plateau, are we entitled to say that the war of liberation has ended."

Yet Allon’s vision was never one of pure military conquest. He saw the military and territorial achievements of the Six-Day War primarily as a political opportunity for Israel to reach agreements with its neighbors under more favorable conditions. Allon was prepared for Israel to make significant concessions in the negotiation process, so long as it remained committed to the fundamental principle of defensible borders. For Allon, this was the opportunity Israel was presented with and the responsibility demanded of its leaders:

"Our historical right to the Land of Israel is the moral basis for Israel's right to exist within any borders, and if I advocate a territorial compromise, it is not because of the absence of historical rights, but in spite of these rights. And for an equally important historical goal – peace… The future map of Israel must indeed draw its inspiration from our historical rights, but it must be determined according to political and strategic consideration. I do not wish to deny the role of mythology in the life of a people, but neither mythological fervor nor theological rulings have the authority to dictate our course of action. The past is important, but our responsibility is first and foremost to the present and the future."

From this premise, Allon approached and tried to shape Israeli policy after the Six-Day War, including the issue of settlement in the new territories, describing the behind-the-scenes formulation of his plan:

“In those distant days of June 1967, when I was considering the possible political solutions, I came up against a hard struggle with that territorial compromise which took the form of a map. A map that sought to give Israel a solid strategic alignment… Whether I was right or not – I saw the need to immediately outline the principles of the map […] in order to mark the areas of new settlement in the territories, which in my opinion is not only permissible, but also desirable, essential and urgent. A map that will mark where new rural and urban settlements should be established and, no less importantly, where such settlements should be avoided, in order to leave options open for a political solution."

In late May 1973, just a few days before Allon said these words, a modest ceremony was held to mark the establishment of a small Israeli outpost in the heart of the Gaza Strip. This outpost would eventually grow into a moshav known as Katif, and its founding marked the dawn of Gush Katif, a bloc of more than a dozen Israeli settlements within the Gaza Strip that would be maintained until Israel’s unilateral disengagement from Gaza in 2005.

These settlements were originally conceived as an expression of the strategy of establishing defensible borders. They were founded under the assumption that in future negotiations with Egypt, Israel would demand border adjustments that would leave it in control not only of the Gaza Strip, but also of the northeastern corner of the Sinai Peninsula. After taking control of the peninsula from Egypt in 1967, Israel began establishing settlements, first military and later civilian, along the coastal plain between Rafah and el-Arish in 1971. Israeli settlement in this region, which came to be known in Israel as Hevel Yamit, was central to the strategy behind the creation of Gush Katif.

In 1982, when the settlements of Hevel Yamit were forcibly evacuated by the IDF so that the entirety of the Sinai Peninsula could be returned to Egypt, as per the terms of the peace agreement, the strategic role of the Israeli settlement in the Gaza Strip was called into question. In conjunction with Hevel Yamit, the existence of Gush Katif was a logical extension of Allon’s doctrine of establishing defensible borders. Without Hevel Yamit, Gush Katif suddenly seemed to fly in the face of that very principle.

For various political reasons, the future of the Gaza Strip, and the Israeli settlements within it, was shrouded in confusion after the Israeli withdrawal from Sinai. Israel’s commitment, in the peace agreement with Egypt, to some form of Palestinian autonomy contributed to deepening doubts regarding the future of Israeli settlement in Gaza. Events in the Strip in the following years, most notably the outbreak of the First Intifada in 1987, left no room for doubt that the continued existence of an Israeli settlement in the heart of a densely inhabited Palestinian area created an untenable security risk. Although Yigal Allon had passed away in 1980, it was in this context that his firm position was voiced by many Israelis:

"If the choice is between a de facto binational state with more territory and a Jewish state with less territory, I choose the second option, provided it has defensible borders. The choice before us in this matter is clear and cruel. If we annex all the densely-populated territories to Israel, while granting full rights to their residents, we will once again be without a Jewish state. If we annex them without granting rights to their residents, we will cease to be a democratic society. But we desire both a Jewish state, albeit one that will always have an Arab minority that will enjoy equal rights, and a democratic society in the fullest sense of the word."

Oslo, the Second Intifada and Disengagement

The First Intifada slowly died out in the early 1990s. The 1991 Madrid Conference revitalized the Israeli-Palestinian peace process, and a year later Yitzhak Rabin was elected Prime Minister. In 1994 Israel and the PLO signed the 'Gaza-Jericho Agreement,' which provided for limited Palestinian autonomy and established the Palestinian Authority. It was unclear what these processes would mean for the fate of the Gaza Strip as a whole, but the city of Gaza was handed over to Palestinian control in 1994. This one move not only dealt a heavy blow to Allon's vision of defensible borders, but also rendered the possibility of connecting the Gaza Strip to the Kingdom of Jordan moot.

Meanwhile, continued Israeli settlement in the Gaza Strip after the withdrawal from Sinai and the evacuation of Hevel Yamit did not facilitate the creation of a defensible border in the area, with dozens of scattered settlements in close proximity and high friction with the Gazan population. The anomalous status of these settlements was thrust into the spotlight with the outbreak of the Second Intifada in 2000, when the reality of two peoples living in one extremely dense space became increasingly difficult and bloody. Caught between Egypt on one side and Palestinian-controlled Gaza on the other, Gush Katif became a constant focal point of friction and violence. The viability of Israeli settlement in the heart of the Gaza Strip was called into question.

Although there were not many left by this point who analyzed the situation through Allon's conceptual lens, it is possible that Prime Minister Ariel Sharon also recognized the strategic futility of maintaining the status quo in Gaza. In any case, it was under Sharon’s leadership in 2005 that Israel unilaterally disengaged from the Gaza Strip, forcibly evacuating the residents of Gush Katif and bringing to an end the historical chapter of Israeli settlement in Gaza.

Hamas Rule

The experiment of a Gaza Strip ruled by the Palestinian Authority and free of Israeli settlement lasted only two years. In 2007, in a violent coup, Hamas seized power in the Strip. Since then, Israel has employed a strategy of maintaining both physical separation between the Gaza Strip and the West Bank and political separation between Hamas and the Palestinian Authority. But over the last decade and a half, as the prospect of a political resolution became more and more distant, conditions became increasingly favorable for Hamas to consolidate their strength, accumulate assets, and wait for an opportune moment to launch a devastating attack.

Today, after more than half a year of war with Hamas, the political future of the Gaza Strip seems more unsettled than ever. But along with uncertainty comes a wide range of possibilities, and now may well be the time to make a significant historical correction by dismantling the Hamas government and returning the Gaza Strip to the discussion in the context of shaping a political solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Without this outlook, Israel’s military achievements, however significant they may be, will dissolve. It is Israel's duty to use these military successes to ensure a better political reality than the one that prevailed here before October 7th.

Now more than ever, Israel is in need of an Allon-esque approach to security, what he referred to as "a strategy of peace." As part of this conception, the possibility of Jordan playing the stabilizing role that Allon suggested in his plan must be reexamined, as many of the geopolitical conditions that Allon described at the time still exist today, despite the passage of time. These conditions lead to the conclusion that Jordan must be a central partner in any political solution, alongside other relevant parties including Saudi Arabia (with whom, on the eve of October 7th, Israel was very close to establishing diplomatic relations, which many analysts see as a central factor in the timing of the Hamas attack). The inadequate attention paid to the Gaza Strip in the peace agreement with Egypt has become a scandal over the years. Postponing a concrete decision on Gaza’s fate for more than half a century has provided Israel with some periods of relative quiet, but it has not created more favorable conditions for solving the root problem, which, as is the way of untreated problems, has only swelled and became more complicated.

Yigal Allon used to tell his critics that despite the flaws and costs of his plan, with the passage of time and in view of the alternatives, they would still find themselves longing for it. If this longing were not the painful reality of our lives, it could be considered a tremendous experiment in political science, a fascinating multinational Middle Eastern experiment that has gone on for over 100 years with the participation of many millions. But this is the reality we face, and it cannot be assumed that time will only work in favor of one side. Israel must assume that its adversaries will always strive to take advantage of opportunities afforded by Israeli weakness or moments of crisis and, as happened on October 7, may very well succeed.

But it is also possible that in the current war, conditions are being created that did not exist before to go back and create a new reality, one without Hamas in the Gaza Strip. Such a reality could also lead to a broader improvement in Israel’s standing and ability to cooperate with relevant countries in the region. The alternative to progress on the political level is to continue waging war with no end in sight, only the possibility of opening additional fronts.

Furthermore, this could be a historic opportunity to revise the model of Palestinian autonomy, as it was inadequately delineated in the framework of the peace agreement with Egypt and later also in the Oslo process and the various initiatives that followed it. Such an adjustment must include an updated approach to the key issue of the relationship between the Palestinian populations on either bank of the Jordan River, where the majority of the Palestinian people live. A political process with enough vision and momentum could force the accepted political structures – the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan and the Palestinian Authority – to change in ways that will better meet the needs of the population that they are supposed to serve.

This is a time of severe crisis that brings with it a regional upheaval that also holds opportunities. After the fall of the Hamas regime, the devastated Gaza Strip and its rehabilitation can once again become relevant for Jordan, as Allon proposed. In any case, the State of Israel will certainly not agree to gamble on its security in the post-October 7th era. The model of Palestinian autonomy must be reimagined in light of the failed experiment Hamas rule in Gaza. Jordan, which is also very much threatened by Hamas and its ilk, may be a partner in such a move, given the encouragement of guarantees and appropriate resources from other Arab countries and the West in general. As Allon described, developing and pursuing a strategy of peace can open the door to unforeseen possibilities:

"Peace is the fruit of a complex process that must be cultivated persistently and one cannot know with certainty when and how it will come. But one should never despair of it. Whoever does not do everything necessary in the present to reach it, may miss it even when a favorable situation arises to achieve it. Therefore, those who wish for peace tomorrow must prepare for it today, even if it is not at hand at the moment. A rational nation, even when it is subject to a murderous war and is aware of the dangers of a renewal of war, can and must conduct a rational policy of peace. That is: to do everything to prevent war and to be prepared, in every respect, should it break out; […] all without falling into the delusional trap of thinking that achieving an agreement depends only on us and our good intentions."

Or Paz-Ivry is an educator and commander of the 8112nd Armored Battalion of the 679th Armored Brigade. He has been serving in active reserve duty since October 7.

This article was translated from Hebrew by Nancye Kochen.